The Vault is Slate’s new history blog. Like us on Facebook; follow us on Twitter @slatevault; find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

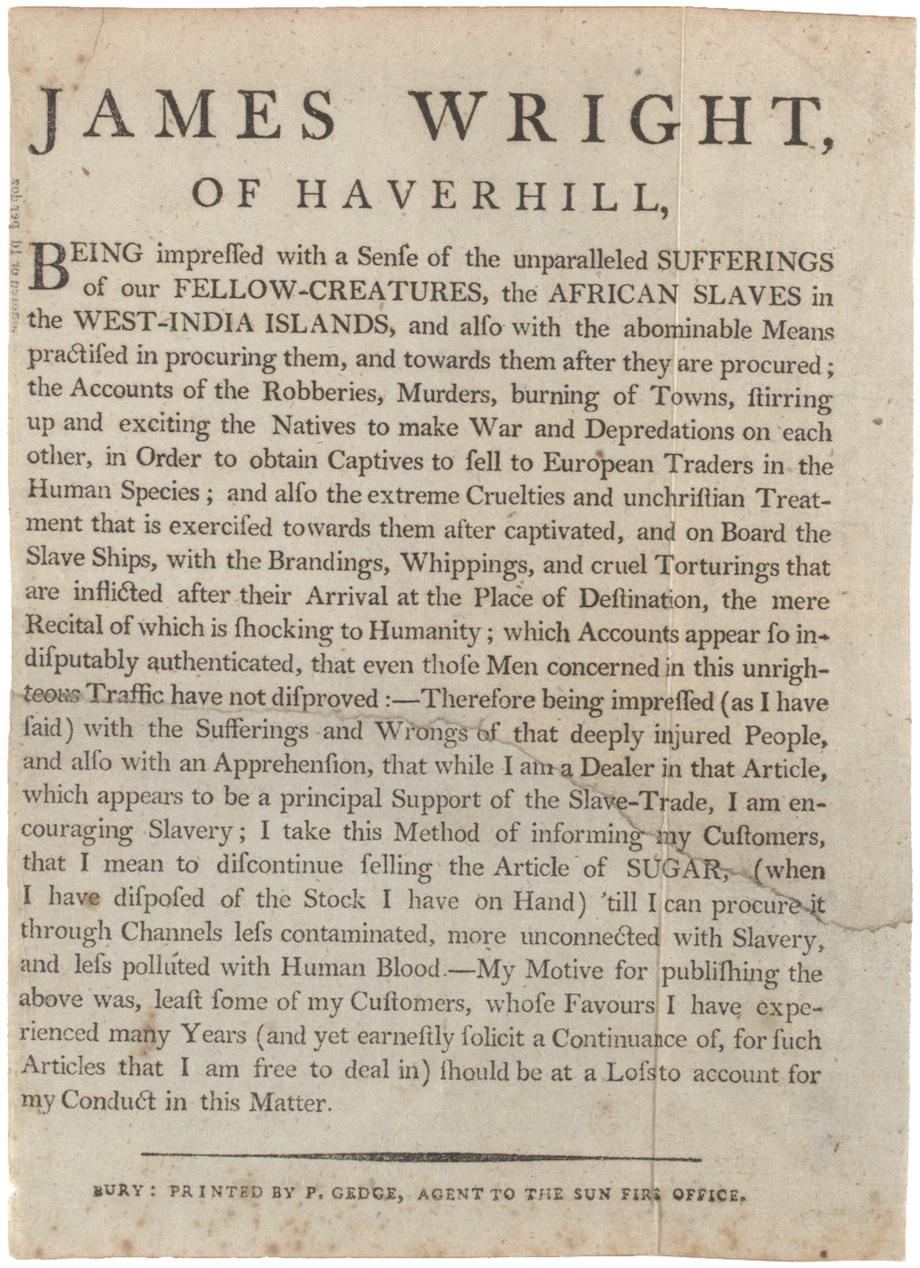

An English merchant published this broadside in 1791, explaining to his customers why he would no longer sell sugar from the West Indies.* The piece is now held in the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

In the broadside, James Wright recounts his reasons: the “extreme Cruelties” of the slave trade, the changes the trade had wrought in African societies, and the dire conditions of the plantations of the “West-India Islands.” Wright had become convinced of his own complicity: “While I am a Dealer in that Article, which appears to be a principal Support of the Slave-Trade, I am encouraging Slavery.”

The sugar trade and the slave trade were inextricably linked. Between 1701 and 1810, according to anthropologist Sidney Mintz, Barbados, one of the major sugar-producing islands, imported 252,000 slaves; Jamaica imported 662,400. In England, some abolitionists began arguing for sugar boycotts in the 1780s. (You can see a 1792 pamphlet arguing for such a boycott here and read a 1788 poem by William Cowper on the subject here.)

James Wright had counterparts across the Atlantic; historian Wendy Woloson has found that some Philadelphia stores advertised their conscientious sourcing of groceries in abolitionist newspapers. But a full-scale boycott of sugar never caught on in the former Colonies.

GLC04614 James Wright, of Haverhill…[Merchant will not sell sugar due to slave labor], 1791. (Courtesy of the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.)

*Correction, Jan. 30, 2013: This blog post originally implied that the broadside was published in America and that James Wright was a Massachusetts merchant, and the headline called the broadside an effort to stop “American slavery.” While the Gilder Lehrman Institute believed that to be the case, based on information they received upon their acquisition of the item, scholars who saw the initial blog post have since proven that Wright was from England and the broadside was printed there. (Return to top.)