The Vault is Slate’s new history blog. Like us on Facebook; follow us on Twitter @slatevault; find us on Tumblr. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

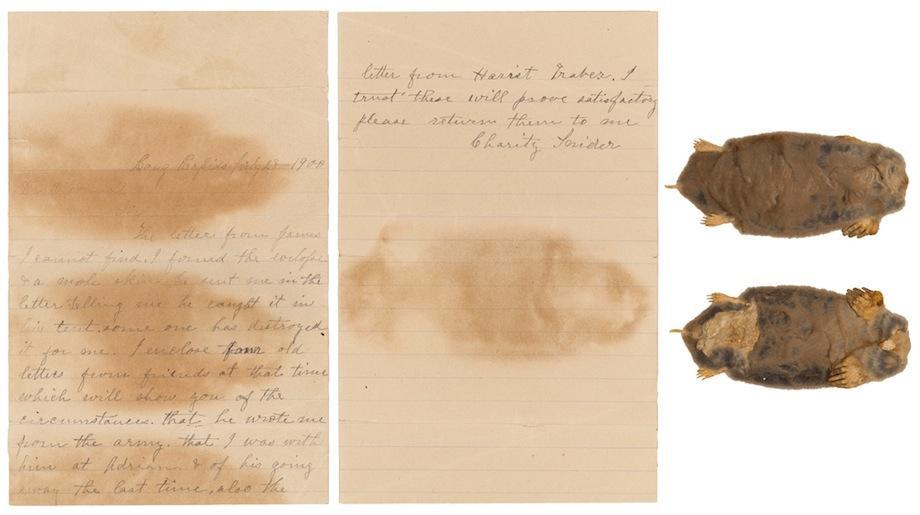

In order to receive a pension, Civil War widows had to prove that they had actually been married to a soldier. Marriage records were far less consistent in the past than they are today, which explains why Charity Snider ended up sending the pressed skin of a dead mole to the federal government.

Snider’s husband, James J. Van Liew, had killed the animal after it infiltrated his Army tent. We don’t know why he sent Snider the skin. It seems like a bizarre love token, but perhaps Van Liew and Snider shared an off-kilter sense of humor.

Snider kept the pelt around for years. By July 1900, when she found herself needing to prove she’d been married to Van Liew, she had lost the original letter that contained the skin. In fact, it seems she may have lost all written correspondence from her husband, which is why she was lucky that he had sent her the mole.

When the letter arrived during the war, she showed the unusual enclosure, and the accompanying missive addressed to “My Dear Wife,” to her friends. Perhaps because of the mole, four of them remembered the letter years later, and they were willing to write testimonials to the government to that effect.

Snider wrapped the mole skin in her explanatory note and sent it along. She got her pension; years later, a National Archives staff member working with the Civil War Widows Certificate Approved Pension Case Files got a funny surprise.

Thanks to Mary Ryan of the National Archives. Read more about this case on the National Archives blog.

Letter from Charity Snider, with accompanying mole skin, from her Civil War Widow’s Pension Application File. Discoloration on the paper is from the mole skin. (WC843258, Record Group 15), National Archives.