The Vault is Slate’s brand-new history blog. Like us on Facebook, and follow us on Twitter @slatevault. Find out more about what this space is all about here.

When he was a young and impoverished lawyer in Springfield, Ill., Abraham Lincoln had an awkward romantic entanglement with a wealthier Kentuckian named Mary Owens. Mary’s sister, Elizabeth Abell, had been trying for years to make a match between the two (who had never met). In 1836, Lincoln told Abell—half in jest—that if Owens wanted to move to Illinois, he would marry her. This was a rash promise that, after spending more time with Owens, he began to regret. When he finally did propose to her, reluctantly, she unexpectedly rejected his suit.

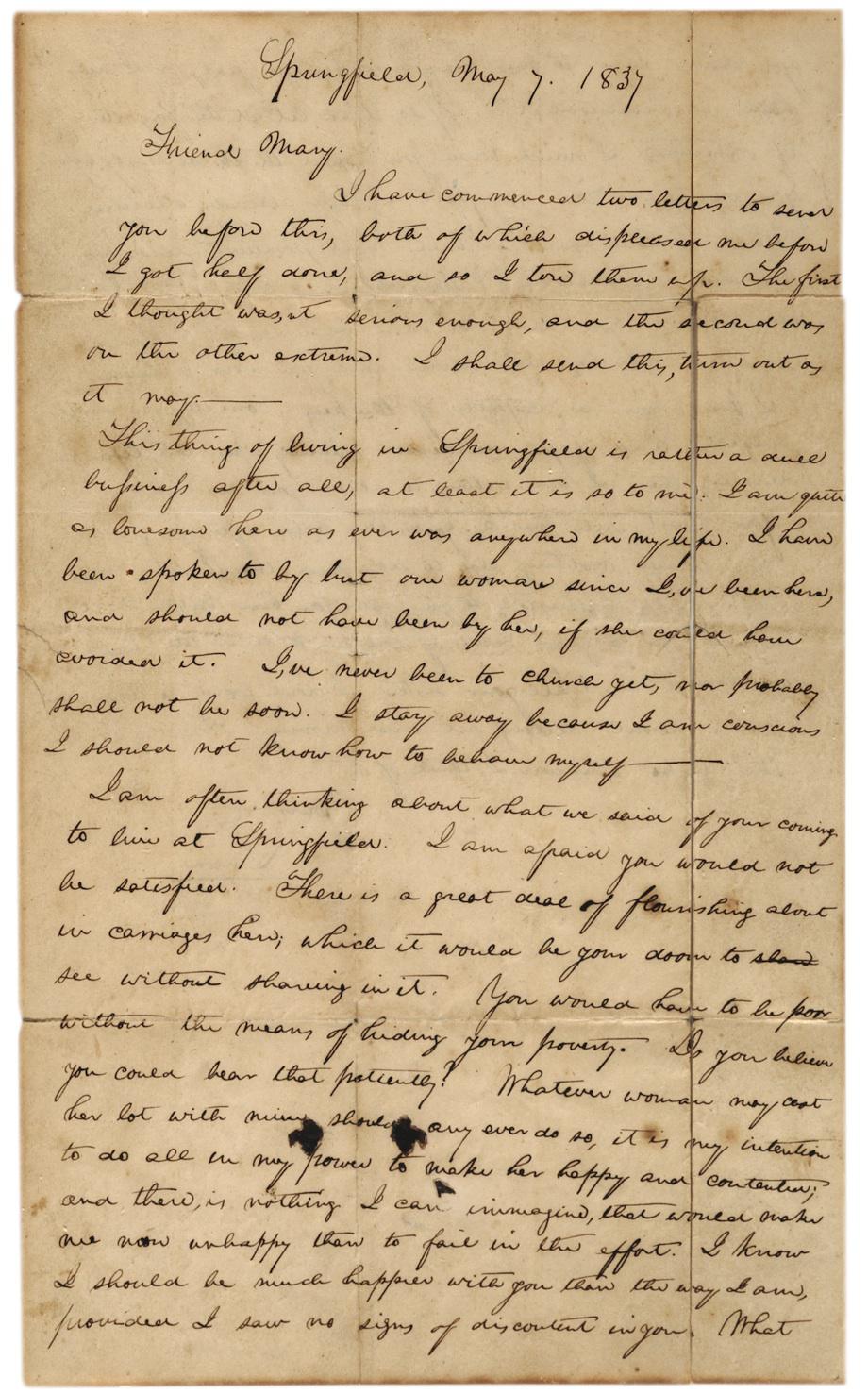

The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History holds one of the three letters that Lincoln wrote to Owens before the proposal, as he struggled to resolve the situation with honor. In this one, dated May 7, 1837, Lincoln tries to convince Mary that she really wouldn’t like living in Springfield as the wife of a man without much money. (Read a full transcript here.)

GLC 08085 Abraham Lincoln to Mary Owens, May 7, 1837. (Courtesy of the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.)

Springfield, he said, was simultaneously too much of a frontier town and too pretentious. “There is a great deal of flourishing about in carriages here,” he wrote, “which it would be your doom to see without sharing in it.” Anxious to drive the point home, he warned: “You have not been accustomed to hardship, and it may be more severe than you now imagine.”

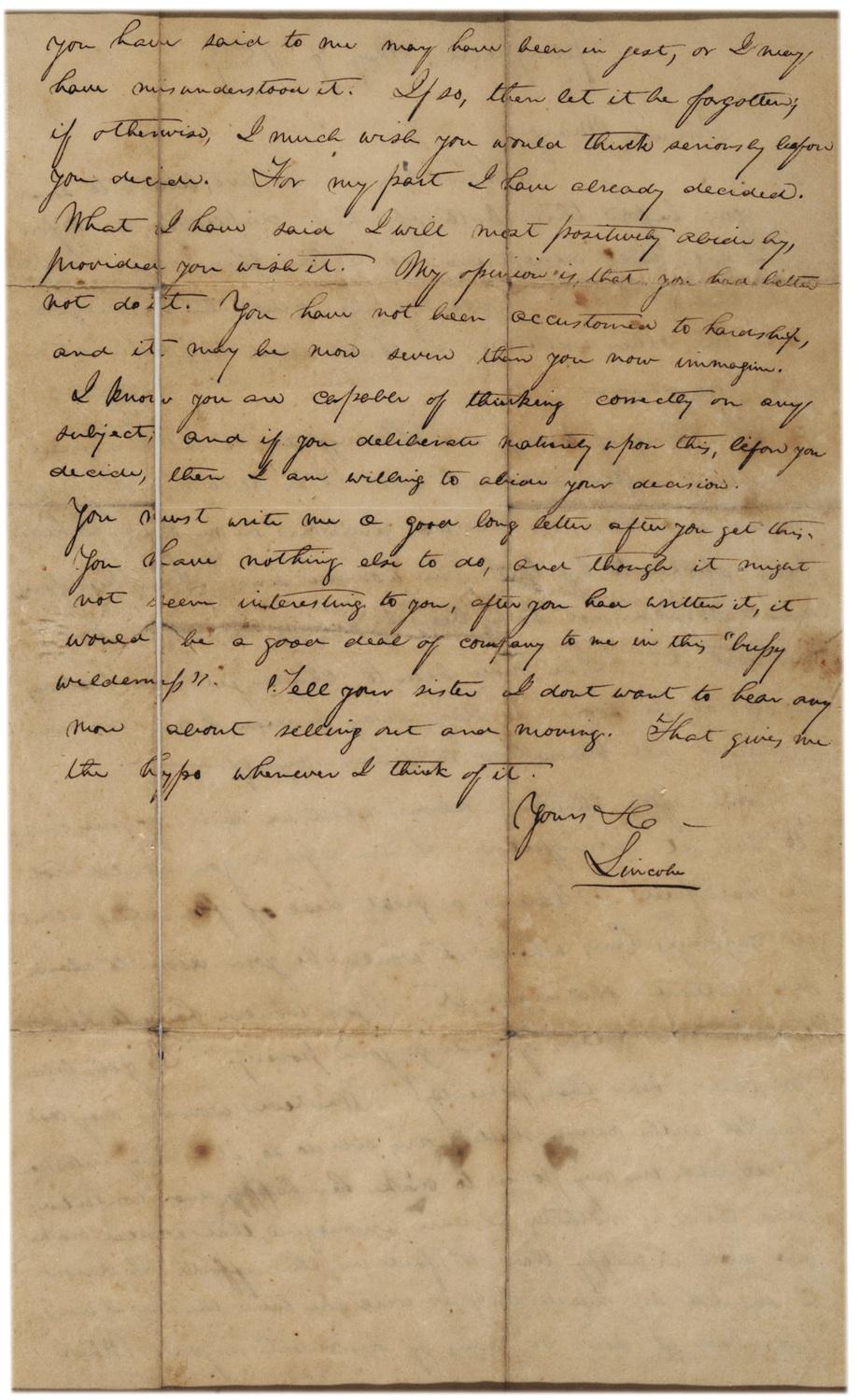

GLC 08085 Abraham Lincoln to Mary Owens, May 7, 1837. (Courtesy of the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.)

Lincoln’s confused wafflings betray a man trying hard to understand Owens’ position and react accordingly. He used many conditionals (“I should be much happier with you than the way I am, provided I saw no discontent in you”) and capped the letter off with the very romantic “What I have said I will most positively abide by, provided you wish it. My opinion is that you had better not do it.”

In a later letter to friends, in which he recounted the story of the “scrape” with no small degree of humor, Lincoln said some quite unkind things about Owens’ physique, but also reserved a fair share of criticism for himself for having so thoroughly misunderstood the situation. “Others have been made fools of by the girls,” he wrote, “but this can never with truth be said of me. I most emphatically, in this instance, made a fool of myself.”

Thanks to Sandra Trenholm of the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Follor the Gilder Lehrman Institute on Facebook or Twitter.