Women’s soccer in America feels brand new. Every four years when the U.S. women’s national team seriously contends for another World Cup trophy and patriotic fans return to the game, commentators and journalists remind us of familiar details for how the sport accelerated into an unofficial women’s national pastime: Title IX in 1972, the rise of the U.S. Women’s National Team and Brandi Chastain’s championship-winning kick in 1999, and Abby Wambach’s head are generally the main talking points. That’s why it sounds so odd to hear about Flo Murphy’s medal.

On the front of the prize are two women kicking a soccer ball. On the back, the words Craig Club are inscribed next to the years 1950 and 1951 and the phrase “First Women’s Soccer League in the USA.” Those years, Murphy and a few dozen other St. Louis women between the ages of 16 and 22 formed what is considered the first official women’s soccer league in America. A few years earlier on the East Coast, hundreds more women were learning the beautiful game at the Seven Sisters colleges as part of a revolutionary P.E. curriculum.

These college students and St. Louis women didn’t form a lasting foundation like Chastain and Mia Hamm. They’re barely remembered. But they are important outliers from an era when young women were too often taught expending energy on sports, or work, or countless other pursuits was a waste of time, jumping in before anyone else would have considered testing the water and demonstrating women could compete. “We didn’t make a big thing of it,” says Murphy, now 84 and living near San Diego. “We just knew there wasn’t any league like us.”

Murphy grew up on the north side of St. Louis, where Sundays pretty much meant church and soccer games for the Irish and British Isles immigrants who brought the game over with them. The best amateur teams resembled today’s Division I in terms of talent, long before the NCAA sanctioned the sport. When the 1950 U.S. men’s national team beat England in one of the biggest upsets in World Cup history, its lineup featured five St. Louis men.

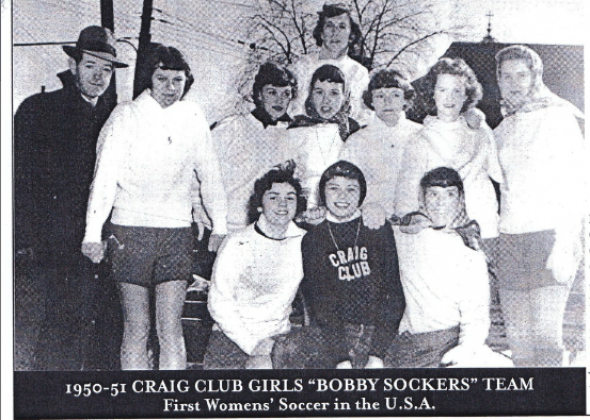

There isn’t some fantastical origin story for the St. Louis women’s league. Basically it started in 1950 when several women expressed interest in competing in the game their brothers and boyfriends played. The league took its name from Walter Craig, a priest at a local church. Anyone could join, no matter her race, religion, or neighborhood, and about 70 women did. They formed four teams: the Bobby Soccers, the Coeds, the Flyers and the Bombers. The field was a bit smaller and the halves a bit shorter. Otherwise, rules were the same as the men’s game. Newspapers covered the league, and hundreds of people watched the 15-game seasons, including prominent men’s players. Women had played soccer in exhibitions and intramurals elsewhere in the U.S. This official league with a following was different, though.

Dave Lange, author of “Soccer Made in St. Louis,” describes the St. Louis style of men’s play as physical. The women didn’t veer far from that ideal. Murphy says they played during the snow. “There were some Sundays when they would cancel the men’s games and they would never cancel ours,” she told me. “To see if we could tough it out, I guess.” For shin guards, Bobby Soccers team captain Mary Dwyer stuffed issues of Reader’s Digest into her socks. “We were a motley looking crew,” Dwyer said. “I’ll tell you that.”

St. Louis provided a relatively enlightened environment for women’s sports, a rarity for the first 75 years of the 20th century. Men with actual medical degrees still believed athletic movements would make a woman’s uterus fall out. The Seven Sisters colleges wanted to disprove these kinds of gender stereotypes, and the St. Louis league was taking their approach to the next level.

Some of those schools had first introduced soccer in the 1920s. Shawn Ladda, a kinesiology professor at Manhattan College and an expert on the history of women’s intercollegiate soccer, says soccer was popular because of its low cost and emphasis on running. Rather than official games, the colleges engaged in “play dates.” Women from Bryn Mawr, Smith and Wellesley, for instance, would intermingle for a series of competitive games.

This early wave of women’s soccer did not turn into a craze. The first varsity women’s college soccer game didn’t take place until 1976 between Brown and Smith. Even with the legal backing of Title IX, women had to fight for recognition. Ladda played on a club team at Penn State University in the late 1970s and early 1980s. She and some teammates approached football coach Joe Paterno during his brief stint as athletic director and asked if their team could be elevated to varsity status.

“He told us he had nothing against soccer, but we didn’t have the money from the university,” Ladda says. “I’m sure Penn State at the time wasn’t in compliance with Title IX, as weren’t 90 percent of universities.”

The Craig Club didn’t start a trend, but it did show that women could thrive at their neighborhood’s treasured game and attract attention for doing so. It disbanded after two years. The women went to college, got jobs and in some cases, like Dwyer, got married (her husband was a soccer player, too).

Last summer, Dwyer was getting her car fixed as the men’s World Cup played on a TV in the background. She told the mechanic about the Craig Club. The man was so floored he asked her to speak at his son’s school. She declined. Dwyer, 85, may have captained one of the first women’s soccer teams in this country, but she considers herself far from an expert. She’s just happy her children and grandchildren took up soccer, and she’s been able to see what the sport has become.

“Even now,” Dwyer says, “I get really excited during the games. Soccer is beautiful.”