In the spring of 1994, the U.S. men’s soccer team assembled for what it expected to be an upbeat meeting. During the gathering, Adidas showed the excited players the primary jersey they’d wear at the upcoming World Cup, the first one ever to be held in the United States. The respect-seeking Americans hoped to mark the occasion by taking the pitch clad in something dignified. That dream died the instant the presentation began.

The 1994 World Cup uniform looked as if it had been conjured by a stoned teenager using Microsoft Paint. The jersey featured a denim print, oddly shaped floating white stars, and bright red trim, and it was made of 100 percent polyester. But as outlandish and stonewashed as it appeared, the design did capture the state of soccer in the United States. Unpolished, loud, and with no regard for international tradition, the kit certainly wasn’t dignified. It was uniquely American. “We were like the cowboys of the world,” midfielder Tab Ramos remembers. “Here we were, wearing jeans.”

By 1994, American soccer had entered a new frontier. The U.S. had qualified for the 1990 World Cup but lost all three of its games. Just a handful of Americans played overseas, and the first season of Major League Soccer was still two years away. As host of the sport’s marquee event, the U.S. Soccer Federation desperately wanted to make a splash. “The whole idea was that this was an American World Cup,” former USSF executive director Hank Steinbrecher says. “We needed to make a statement about soccer in America.”

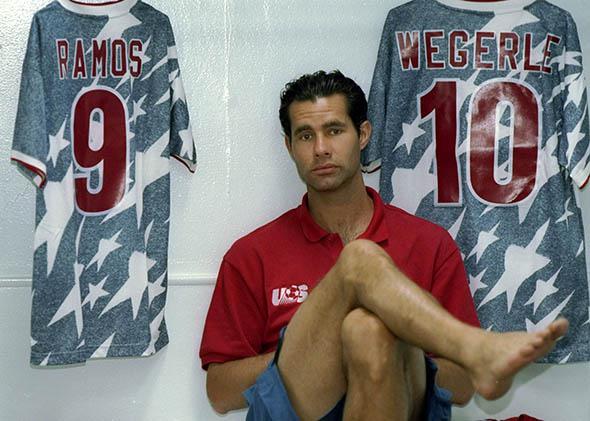

The U.S. national team’s Roy Wegerle looks thrilled to pose in front of his jersey.

Photo by Mike Powell/Allsport/Getty Images

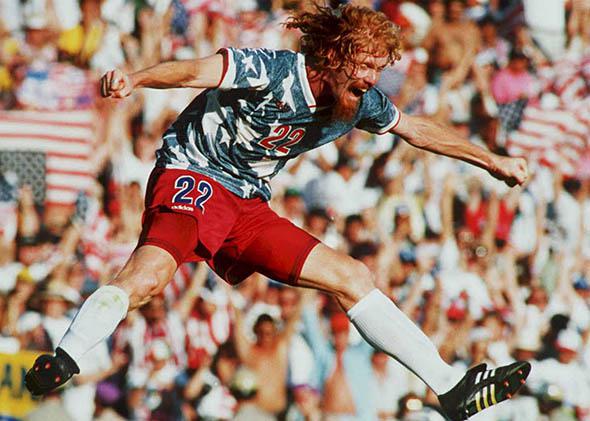

That statement wasn’t one the American players were particularly proud of. After the uniform unveiling, the normally loquacious Yanks didn’t say a word. “It was the longest silence I’d ever heard from our team,” remembers forward Eric Wynalda. Then, laughter broke out. Defender Paul Caligiuri thought the jersey looked like a clown suit. Even shaggy-haired, guitar-playing center back Alexi Lalas, who once wrote and performed a song called “Kickin’ Balls,” hated it. In fact, he thought the squad had been pranked. “I’d be lying if I said people weren’t looking around for the hidden camera,” he says.

Lalas, now an analyst for ESPN, says that there was a huge amount of pressure for the 1994 squad to play well—to not embarrass itself on home soil, and to pave the way for a potential domestic soccer league. These uniforms, he says, were like a target on the players’ backs. Now, they didn’t just have to play well. They had to play well while wearing denim.

Dressing up your fledging national team like a bunch of psychedelic patriots may seem like a risky move, but it was a calculated one. “In my world, if you have a strong reaction, that’s a positive,” says Peter Moore, then global creative director at Adidas and president of the German company’s American subsidiary. If people are angry, then at least they’re paying attention.

Moore knew this from experience. While working for Nike in the 1980s, he designed the original Air Jordans. Due to the black-and-red high-tops’ garish color scheme, the NBA initially docked Michael Jordan $5,000 for every game he wore them. Nike paid the fines, ran a commercial that openly mocked the ban, and by the end of 1985, the Air Jordan line reportedly had earned the sneaker giant more than $100 million.

A few years later, Nike outfitted brash teenage tennis phenom Andre Agassi with stonewashed denim shorts. This didn’t exactly usher in a roaring jeans-as-athletic-wear boom, but it did lay the groundwork for the denim U.S. soccer jersey.

Photo by Stephen Dunn/Allsport/Getty Images

The problem for Adidas was that soccer players couldn’t lug around heavy cotton tops for 90 minutes. But a denim print might work. Adidas decided it would suffice to make the shirts look like the quintessential American fabric. Moore says designers created the jersey’s distinctively distorted pattern by laying stars on the shirts, then dragging them across the glass surface of a Xerox machine as it scanned.

Mary McGoldrick, then Adidas America’s director of design and product development, remembers showing sketches of the jersey to her more conservative German colleagues. “Uh, that doesn’t look like Adidas,” one told her. That year, the company supplied several teams with relatively outré jerseys—Germany’s had a checkerboard pattern and Nigeria’s had an intricate print—but none drew the attention, and scorn, of the USA’s denim kit. “Who else could, or would, do a shirt that looked like it was a pair of 501 jeans?” Moore says.

The best you can say for the faux-denim jersey is that it could’ve been a whole lot worse. In a 2011 interview with the wonderfully named blog the Denim Kit, Adidas’ Drew Gardner revealed that the company’s uniform imagineers pondered outfitting the team in tie-dye. But a kit befitting the 1992 Lithuanian basketball team was not to be.

Does this look any better?

Photo by Al Bello/Allsport/Getty Images

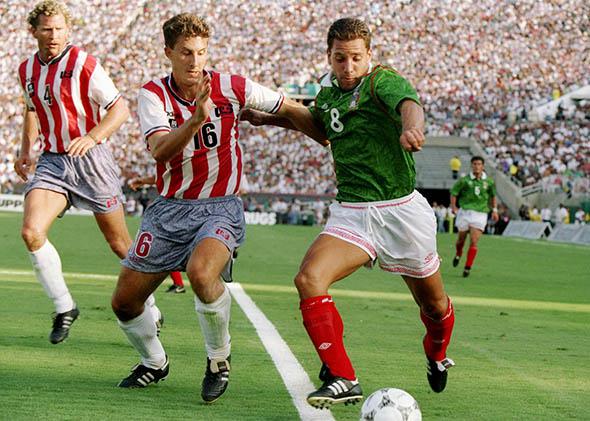

The Americans wore the denim jersey for the first time in a March friendly against Bolivia at the Cotton Bowl. It was the perfect attire for the national team’s cross-country, publicity-drumming barnstorming tour. From January to early June, the national team played more than a dozen exhibitions, including a 1–0 win over Mexico in front of 91,000 at the Rose Bowl. That day, the U.S. wore its slightly less eccentric secondary World Cup jersey, which—like an American flag flapping in the wind—featured wavy red and white stripes. (The outfit also included denim-print shorts, but those were eventually nixed for red ones.)

As the World Cup neared, the players laughed about their uniforms to keep from crying. In 1994, People named U.S. midfielder John Harkes to its “Most Beautiful” list. When Ramos saw what he’d be wearing against America’s archrival, he said, “Even John Harkes cannot make this uniform look good.” Another player joked that the wavy stripes on the secondary kit made the ginger-haired Lalas look “like Raggedy Ann.” The jokes were an obvious coping mechanism, a way to mask the Americans’ self-consciousness. After all, how can the international soccer community take you seriously if you resemble early ’80s Bruce Springsteen? “It was kind of their first time to the dance,” McGoldrick says. “You don’t want to stick out.”

But they did. FIFA’s World Cup uniform assignments guaranteed the host’s conspicuousness. The U.S. wore the denim jersey for each of its three group-stage games. In their opening match, the Americans tied Switzerland 1–1 at the Silverdome. Then, with the help of a tragic own goal, they managed to defeat Colombia 2–1 at the Rose Bowl. After the upset, some of the giddy players draped themselves in American flags. “As soon as we beat Colombia, it was, ‘These jerseys are cool,’ ” Caligiuri says. It may not have been the orange of the Netherlands, or the blue and white stripes of Argentina, but all of a sudden, the patriotic collage of a shirt sort of felt right. “You can wear black leather and tassels,” Lalas says, “and if you play well, it’s going to look good.”

On July 4, in the Round of 16 at Stanford Stadium, the Americans’ improbable run ended with a 1–0 loss to eventual champion Brazil. The next day, the San Francisco Chronicle reported that Adidas had sold “at least” 60,000 replica U.S. jerseys at World Cup venues at $60 a pop. “We could have made a million of them,” Shelley Franks, product manager of soccer apparel for Adidas America, said at the time. “Nobody can get their hands on them.”

For U.S. Soccer, which was in the middle of staging what ended up being the best-attended World Cup ever, this was validation. “We needed to gain attention,” Steinbrecher says. “And those uniforms did it.”

Eventually, some of the players warmed up to the denim. “Those designers, they did their job,” Wynalda says. Lalas still has a fan-made portrait of himself in a denim kit. He calls its style “beautiful arrogance.” In 1994, Caligiuri starred in a Pert Plus shampoo commercial while decked out in a stonewashed denim U.S. shirt.

When the U.S. scored against Colombia, the jersey started looking a whole lot better.

Photo by David Cannon/Getty Images

Over the last two decades, the U.S. has shed its reputation as a plucky upstart. The national team has appeared in every World Cup since 1990; its top players have now found success abroad; and its coach, Jürgen Klinsmann, recently signed a contract extension that will pay him $3 million per year. MLS, too, looks like it’s here to stay, recently inking a TV deal worth $90 million annually.

But even though soccer is creeping toward the mainstream here, the U.S. is still trying to fit in among the world’s powers. That’s likely why, with a few exceptions—including this year’s away jersey, which shares a color scheme with a Bomb Pop—the national team’s uniforms now appear so traditional. Nike, the squad’s supplier since 1995, has experimented with different hoops, sashes, and crests, but it hasn’t come up with anything as creative or strangely iconic as the denim jersey.

Steinbrecher, the former executive director of the U.S. Soccer Federation, still sees denim-clad fans at U.S. games. What does he think of the stonewashed shirts now? “They’re ugly as sin,” Steinbrecher says, “but they work.”