With less than a month to go before the World Cup kicks off, it’s time to get acquainted with who’s going to Brazil. For the next several weeks, Harrison Stark will tell you everything you need to know about all 32 countries, looking at how their rosters stack up and what role soccer plays in each nation’s culture and politics. The previews will run in reverse order of the countries’ chances of winning the World Cup. This second post covers a team that’s looking good for 31st place: Iran. [Correction, May 30: This post originally stated that these previews were running in reverse order of the countries’ predicted finish at the World Cup. They are running in reverse order of the countries’ chances of winning the World Cup.]

When North Korea failed to qualify for this year’s tournament, there may have been some brief concern that we’d have a World Cup without a member of the “Axis of Evil.” Thankfully, Iran stepped forward to fill the void.

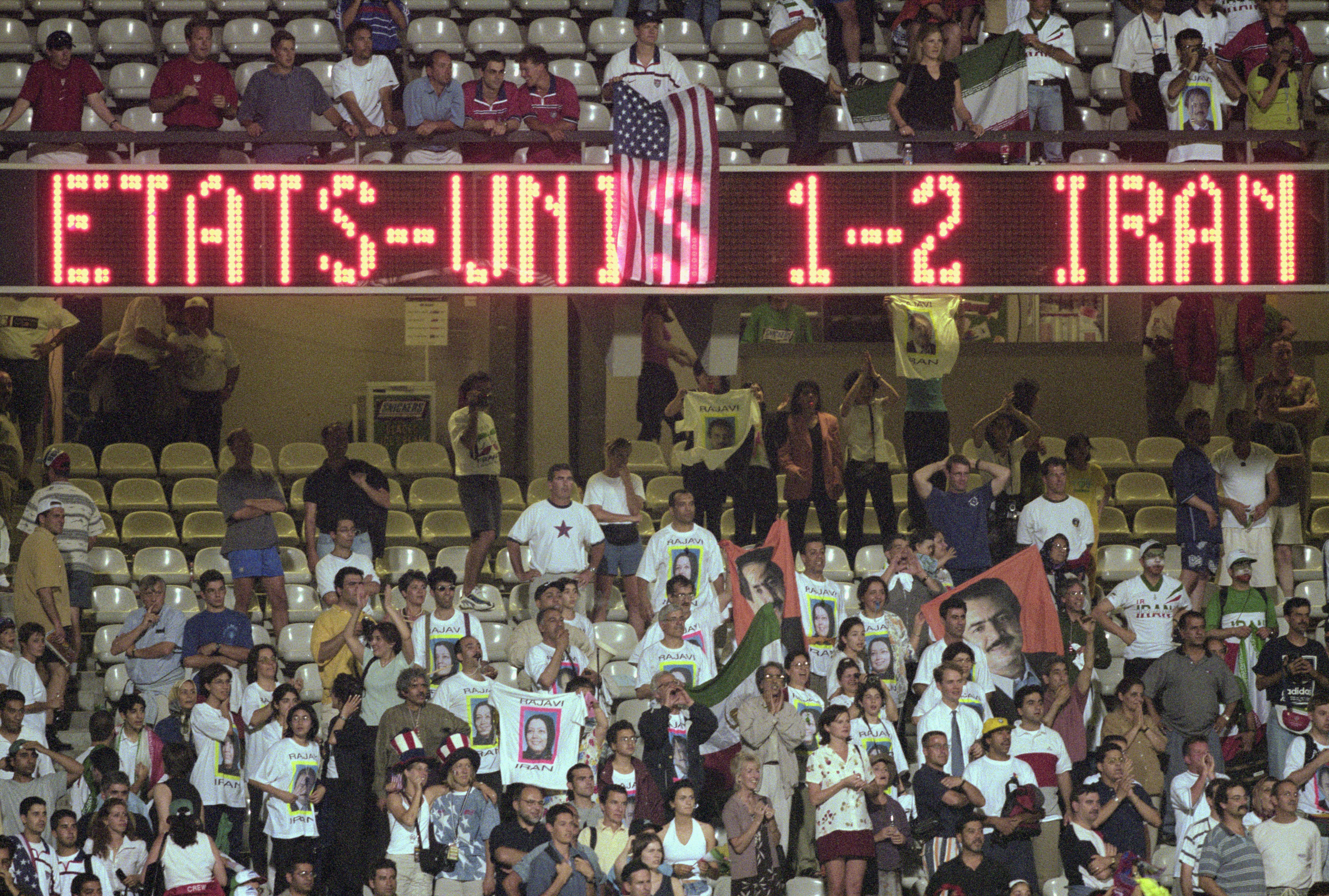

Unlike Kim Jong-un’s favorite team, Iran has made it to several World Cups in the modern era. “Team Melli” most recently went to the German-hosted 2006 tournament, an occasion marked by then-president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad declaring that Israel should be wiped off the map and that Auschwitz was a “fairy tale.” Those pronouncements led the German Green Party and others to call for the team to be thrown out of the tournament. That didn’t happen, but the 2006 event didn’t go so well for Iran, as they brought home just a single point. The Iranians did far better in 1998, when they went out in the group stage but not before beating the “Great Satan” USA, ensuring that team members enjoyed royal status for life.

The link between soccer and politics has always been explicit in Iran. Ties between soccer and the state run deep. Ahmadinejad was said to be a huge soccer fan and vocal in his tactical preferences, which led to a 2006 ban from all international competition because of “government interference.” When former coach Ali Daei was sacked after a 2–1 loss to rival Saudi Arabia, a mass text went out to all of the government’s political supporters that read: “Due to the importance of national public opinion to Dr. Ahmadinejad, Ali Daei has been forced out.”

But that street runs both ways. Before the 2009 elections, an Iranian voter told the Guardian that he had turned on Ahmadinejad because the team was underperforming, blaming the president for recent defeats: “For the last four years our national team has kept being beaten. Under [Mohammad] Khatami we did really well. But when there is no trust in politics footballers don’t play with trust either. If [Mir-Hossein] Mousavi becomes president, Iranian soccer will improve along with everything else.”

Mousavi lost in a highly suspicious election, and the soccer team has since become a conduit for more explicit political action. In June of 2009, several Iranian players wore green wristbands during a match as a symbol of support for Mousavi. After this act of protest, these men were reportedly “retired” from the national team (though the Iranian football association denies this).

Despite its ties to the ruling regime, soccer isn’t just a sport for pro-government types. As in many repressive countries, Iranian soccer stadiums rank among the few places where crowds can legally gather, ensuring that domestic teams like Tehran’s Persepolis FC and Isfahan’s Sepahan FC enjoy huge home support. Soccer can offer possibilities for organizing that would otherwise be impossible. When Iran qualified this past fall, fans filled the streets, marching without the usual police presence. And when Iran played Bahrain in its penultimate qualification match in 2005, around 200 women forced themselves into the game—a first in more than 20 years—chanting, “My right is also a human right.” (It’s also worth noting that the women’s national team became embroiled in an international controversy two years ago when it was banned from the 2012 Olympics by FIFA because the players wore headscarves.)

Qualification was a cause for celebration, but Iran’s recent political position has not helped its World Cup chances. It’s one thing to convince your players to play a friendly in San Francisco or Paris. It’s another to get them to play in Tehran. Whereas teams like Brazil and England have played in dozens of recent exhibition games, allowing them to experiment with formations and personnel groupings, Iran has averaged only a single friendly per year. Current coach Carlos Queiroz complains, “I always tried to do my best and keep the team fully prepared. I have to call my friends [Sir Alex] Ferguson, [José] Mourinho, and [Fabio] Capello to get their advice for better decisions because I am not magician to do without financial support.” The country’s football association is almost bankrupt, with U.S.-led sanctions blamed as the cause.

But while Iran is isolated in many ways, its soccer set-up is remarkably cosmopolitan. Queiroz is Portuguese, and many of the Iranian players have spent their entire adult lives in Europe (the team features youth internationals from both Holland and Germany). There’s even an American connection. The team’s goalkeeping trainer is American Dan Gaspar, former head coach at the University of Hartford, and its right back is American-born and bred Steven Beitashour, from San Jose.

This is a very different team from 1998 or 2006. They’re not a threat to advance in Brazil, but they won’t be pushovers either.

Photo by ATTA KENARE/AFP/Getty Images

Match Schedule: Iran is in Group F, which is far from the Group of Death. Its first match, against Nigeria on June 16, carries the possibility of early points. That brief glimmer of hope will likely be crushed against Argentina on June 21 and Bosnia and Herzegovina on June 25.

How They Line Up: The Iranians will take the field just like everybody else, in a 4-2-3-1.

Key Players: Not many of these guys will be household names, but this is a reasonable roster. Up front, Charlton Athletic’s Reza Ghoochannejhad will lead the line. Struggling to settle in England, he’s been prolific since he made his Iranian debut in qualifying, scoring eight goals in 2013. Behind him, Fulham’s Ashkan Dejagah will be the creative fulcrum—he’s one of the few players to emerge from Fulham’s disastrous season with any credibility. And in the middle, it’s Iran’s captain, Javad Nekounam, 33. Known as the “Prince of Persia,” he was immense in his prime when he played for Spanish side Osasuna. He’s slower today, but still solid and authoritative as a deep-lying playmaker.

Defense is a problem. At the back, the American-born Steven Beitashour has been solid in MLS, playing for the Vancouver Whitecaps, but the World Cup is a different ball game. Jalal Hosseini (Persepolis) is at least experienced, but is hardly world class. And in net, German-born Daniel Davari (the Bundesliga’s Eintracht Braunschweig) will probably get the nod, though none of Iran’s goalkeepers stood out during qualification. Iran could be this year’s Australia—giving out goals galore.

Rising Star: Keep an eye on Alireza Jahanbakhsh, a 20-year-old winger plying his trade in the Netherlands. He’s only made a few appearances for the Iranian senior team but could take some of the burden off Dejagah.

Previous entries: Australia

Want more World Cup previews like this? You can read all of Harrison Stark’s country-by-country guides by purchasing the e-book The Global(ized) Game: A Geopolitical Guide to the 2014 World Cup for $3.99.

Some of this material has been adapted from World Cup 2010: The Indispensable Guide to Soccer and Geopolitics by Harrison Stark and Steven D. Stark.