On Friday, the Louisiana Supreme Court declined to hear an important appeal involving the constitutional right to counsel. The case involves a man who’d voluntarily agreed to speak with the police. When Warren Demesme realized that the cops suspected him of child rape, he told them, per the trial court transcript, “I know that I didn’t do it, so why don’t you just give me a lawyer dog ‘cause this is not what’s up.” The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that when a suspect asks for an attorney, the interrogation must end and a lawyer must be provided. But the police disregarded Demesme’s request, and the trial court ruled that the statements he subsequently made can be used to convict him.

Demesme appealed, arguing that his Fifth and Sixth Amendment right to counsel had been violated. A state appeals court held that they were not, and now the state Supreme Court has declined to review that judgment, with only Justice Jefferson Hughes III voting to take Demesme’s appeal. Justice Scott Crichton penned a brief opinion concurring in the court’s decision not to hear the case. He wrote, apparently in absolute seriousness, that “the defendant’s ambiguous and equivocal reference to a ‘lawyer dog’ does not constitute an invocation of counsel that warrants termination of the interview.”

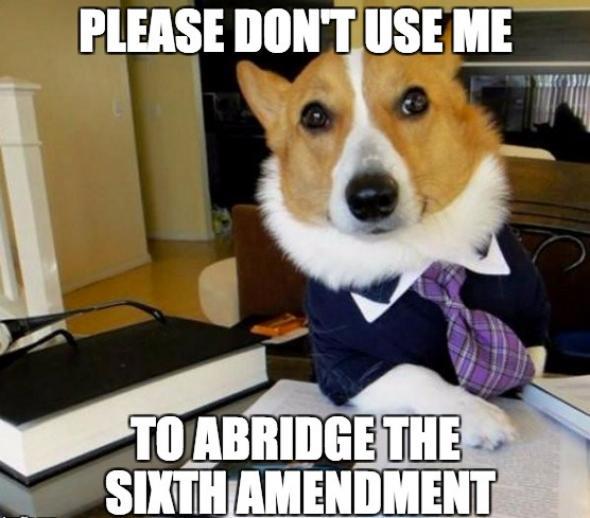

Reason’s Ed Krayewski explains that, of course, this assertion is utterly absurd. Demesme was not referring to a dog with a license to practice law, since no such dog exists outside of memes. Rather, as Krayewski writes, Demesme was plainly speaking in vernacular; his statement would be more accurately transcribed as “why don’t you just give me a lawyer, dawg.” The ambiguity rests in the court transcript, not the suspect’s actual words. Yet Crichton chose to construe Demesme’s statement as requesting Lawyer Dog, Esq., rather than interpreting his words by their plain meaning, transcript ambiguity notwithstanding.

In doing so, Crichton (and the trial court) may well have run afoul of Davis v. United States, the controlling U.S. Supreme Court precedent on this matter. In Davis, the suspect had told his interrogators: “Maybe I should talk to a lawyer.” No lawyer was provided, the interview continued, and the suspect made incriminating statements that were later used to secure his conviction. The Supreme Court held that none of this violated the Constitution. It reasoned that, in order to invoke his Fifth and Sixth Amendment rights, “the suspect must unambiguously request counsel.” The court elaborated:

If the suspect’s statement is not an unambiguous or unequivocal request for counsel, the officers have no obligation to stop questioning him. … [H]e must articulate his desire to have counsel present sufficiently clearly that a reasonable police officer in the circumstances would understand the statement to be a request for an attorney.

The constitutional standard, then, is whether “a reasonable police officer in the circumstances” would interpret the suspect’s words as a request for counsel. Demesme’s statement plainly clears this bar. The Davis court was quite explicit that a suspect need not “speak with the discrimination of an Oxford don.” He need only get the point across. Yet because Crichton refused to interpret Demesme’s words as a reasonable police officer surely would, he asserted that no constitutional violation occurred.

Ironically, Crichton’s musing probably makes this case more vulnerable to U.S. Supreme Court review and reversal. The justice unintentionally illustrated a real problem: Courts can manipulate the “reasonable police officer” standard to conform to their own syntactic preferences, transforming a straightforward if informal request for a lawyer into argle-bargle. Police officers can then follow their lead, willfully misinterpreting anything but the most polished and proper demand for a lawyer.

The Supreme Court can forestall this constitutional subversion by taking Demesme’s case—presuming he appeals—and clarifying that a “reasonable police officer” may not deliberately ignore the intent of a suspect who colloquially but unequivocally asks for a lawyer. Otherwise, lower courts and police officers can wriggle out of the Constitution by pretending to be hound-mad boneheads.