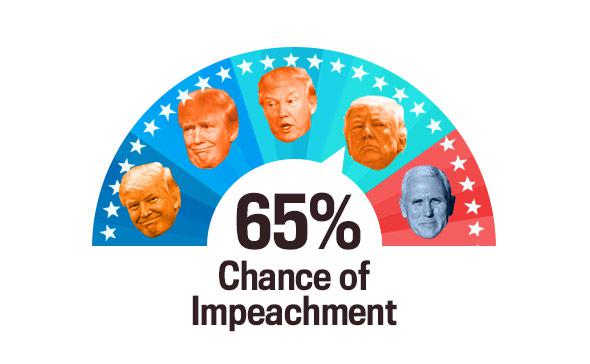

In the tradition of the Clintonometer and the Trump Apocalypse Watch, the Impeach-O-Meter is a wildly subjective and speculative daily estimate of the likelihood that Donald Trump leaves office before his term ends, whether by being impeached (and convicted) or by resigning under threat of same.

Democrats spent most of 2015 and 2016 pointing out that Donald Trump said racist things and cultivated racist supporters. It was all true—and it didn’t get the Democratic Party anywhere at all. Many voters realized Trump was racist and voted for him anyway. Now, after the deadly violence in Charlottesville, we have another situation in which a clear majority of Americans agree on something: White supremacists are bad, and it was bad for Donald Trump to defend them. To be crassly political, how can Democrats turn that consensus into the kind of votes they need to actually do some good vis a vis the Trump agenda?

The party seems to have begun by noticing where it was in Charlottesville that the neo-Nazis and KKK members were rallying: Around a Robert E. Lee statue that may or may not be removed by the city. House minority leader Nancy Pelosi has called thus for statues of Confederate figures to be removed from Congress, while Democratic New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker has proposed a bill that would do the same thing. A crowd of activists in North Carolina, meanwhile, staged a high-profile rally Thursday to defend the individuals who’ve been charged with misdemeanors for pulling down a statue of a Confederate soldier that stood outside the Durham County courthouse. Liberal-leaning publications such as Slate have taken up the issue.

On the merits, ending the practice of officially honoring slaveholders who killed hundreds of thousands of American soldiers makes perfect sense to this writer. Politically, though, there’s evidence that it is not necessarily a winning game. Via PBS NewsHour:

It seems that a majority of Americans, while they don’t approve of Trump’s response to the Charlottesville rally—i.e. blaming anti-racist protesters for violence and asserting that “some very fine people” had participated in the part of the rally that involved carrying torches and chanting Nazi slogans—don’t feel like “tearing down” images of Lee and other Confederate figures is an appropriate response. Trump, encouraged by now-ex-adviser Steve Bannon, is now trying make political hay out of the idea that Democrats are destroying “history” by targeting statues, which, given those numbers, could be pretty effective. The median white voter might not like the critical, indignant statement that monument removal makes about his or her past.

This is why #NeverTrump Republican operative Tim Miller suggests that Democratic activists and politicians would be better off simply hammering Trump for his white supremacist apologism:

The question remains, though: How do you turn that 75-80 percent agreement into party support? How do you turn revulsion toward the white supremacists in Charlottesville into an emblem of a problem that the typical (white) voter doesn’t feel implicated by, and which the typical voter of any race might see themselves as benefitting from the solution to? One blogger’s suggestion: Point out that the defining image of Charlottesville—of entitled individuals angrily asserting their right to a dominant position in society based on nothing other than skin color—is a challenge to basic American ideals of fairness. It’s an accusation that resonates with many appealing aspects of the current Democratic platform.

To wit: Elizabeth Warren, in a recent speech at the Netroots Nation conference in Atlanta, discussed “racist voter ID laws and voter suppression tactics” in the same context as pension-destroying Wall Street fraud. They’re both different ways, Warren explained, that the proverbial playing field can get tilted by a “rigged” system which rewards cheating and hoarding at the expense of hard work. It’s a similar idea to that explored by Slate’s Jamelle Bouie in his piece about Jesse Jackson’s 1980s presidential campaigns, which stressed the common threads between struggling groups and between social problems. Bouie writes that Jackson emphasized the connections between campaigning for higher wages and campaigning for civil rights; for her part, Warren draws an explicit connection between “a dad who’s worried that his kid will have to move away from their factory town to find good work” and “a mom who’s worried that her kid will get shot during a traffic stop.” The common link is fairness: Asking for fair treatment from police, asking for fair treatment from an employer, asking to be given the same opportunities as everyone else and then rewarded on the basis of what you’ve accomplished. The Charlottesville rally, meanwhile—and Donald Trump’s entire life, really—stands for something else altogether: Getting to be on top just because of the way you were born. Democrats shouldn’t miss an opportunity to make the contrast as clear as possible.

Samuel Corum/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Photo illustration by Natalie Matthews-Ramo. Photos by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images, Win McNamee/Getty Images, Chris Kleponis-Pool/Getty Images, Drew Angerer/Getty Images, and Peter Parks-Pool/Getty Images.