On Monday, in an impassioned opinion written by Justice Anthony Kennedy, the Supreme Court expanded Sixth Amendment jurisprudence to create a constitutional safeguard against racist juries—much to the irritation of the court’s three other conservatives, all of whom dissented. The 5–3 decision marks a landmark affirmation of the right to a truly impartial jury trial and bolsters the court’s commitment to combating racism in the criminal justice system.

The case of Peña-Rodriguez v. Colorado began when Miguel Angel Peña-Rodriguez, a Hispanic man, was accused of sexual assault by two teenage girls. A jury convicted Peña-Rodriguez of this crime based exclusively on the girls’ own testimony; no physical evidence linked him to the assault, and he claimed he had been misidentified. After trial, a conscientious juror came forward to inform Peña-Rodriguez that another juror, a former police officer, had tainted deliberations with blatant bias. The racist juror allegedly declared that, based on his professional experience, he knew that “Mexican men” have “a sense of entitlement” and a “bravado” that makes them think they can “do whatever they want” with women. In his own experience, “nine times out of 10” Mexican men were guilty of “being aggressive toward women and young girls.”

Peña-Rodriguez asked the court to grant him a new trial. The court refused, citing a Colorado “no-impeachment” rule that prevents jurors from testifying about statements made during deliberations. Peña-Rodriguez ultimately appealed his case to the Supreme Court, arguing that the Sixth Amendment—which guarantees the right to trial “by an impartial jury”—must supersede the no-impeachment rule in instances of racial bias.

Given the plain text of the Sixth Amendment—“In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed”—you might expect this case to be very easy. A jury tainted by racist comments cannot seriously be considered “impartial,” after all, so the Constitution would seem to safeguard Peña-Rodriguez’s right to a new trial. But there is a wrinkle here: The no-impeachment rule has a historical pedigree that predates the Sixth Amendment. From the nation’s founding, courts have forbidden, or strictly limited, jurors’ ability to testify about deliberations following a verdict. These rules emerged out of a legitimate concern that jurors feel they can engage in robust and honest deliberations without having their verdict later called into question because of a stray comment made in the jury room.

But, as Kennedy explained, the 14th Amendment—which extended the Sixth Amendment’s protections against states—somewhat changed this calculus. The “central purpose” of the 14th Amendment, Kennedy noted, “was to eliminate racial discrimination emanating from official sources in the States.” Indeed, the 14th Amendment was designed, in part, to remedy “racial discrimination in the jury system,” which was rampant in the South. “To take one example,” Kennedy wrote, “just in the years 1865 and 1866, all-white juries in Texas decided a total of 500 prosecutions of white defendants charged with killing African-Americans. All 500 were acquitted.”

“It must become the heritage of our Nation,” Kennedy insisted, “to rise above racial classifications that are so inconsistent with our commitment to the equal dignity of all persons. This imperative to purge racial prejudice from the administration of justice was given new force and direction” by the 14th Amendment. Racial bias in jury deliberations presents “a familiar and recurring evil that, if left unaddressed, would risk systemic injury to the administration of justice”:

This Court’s decisions demonstrate that racial bias implicates unique historical, constitutional, and institutional concerns. An effort to address the most grave and serious statements of racial bias is not an effort to perfect the jury but to ensure that our legal system remains capable of coming ever closer to the promise of equal treatment under the law that is so central to a functioning democracy.

Thus, Kennedy concluded, the no-impeachment rule must give way when, “after the jury is discharged, a juror comes forward with compelling evidence that another juror made clear and explicit statements indicating that racial animus was a significant motivating factor in his or her vote to convict.”

To my mind, this decision is just common sense. The Sixth Amendment, read in conjunction with the 14th, obviously prohibits racial discrimination by a jury. Really, the only question presented by Peña-Rodriguez was whether this discrimination is so egregiously unlawful that, when it is present, the Constitution must override the no-impeachment rule. The correct answer, in light of the 14th Amendment’s profound commitment to racial equality, is yes. Kennedy hammers this point home in his stirring peroration:

The Nation must continue to make strides to overcome race-based discrimination. The progress that has already been made underlies the Court’s insistence that blatant racial prejudice is antithetical to the functioning of the jury system and must be confronted in egregious cases like this one despite the general bar of the no-impeachment rule. It is the mark of a maturing legal system that it seeks to understand and to implement the lessons of history. The Court now seeks to strengthen the broader principle that society can and must move forward by achieving the thoughtful, rational dialogue at the foundation of both the jury system and the free society that sustains our Constitution.

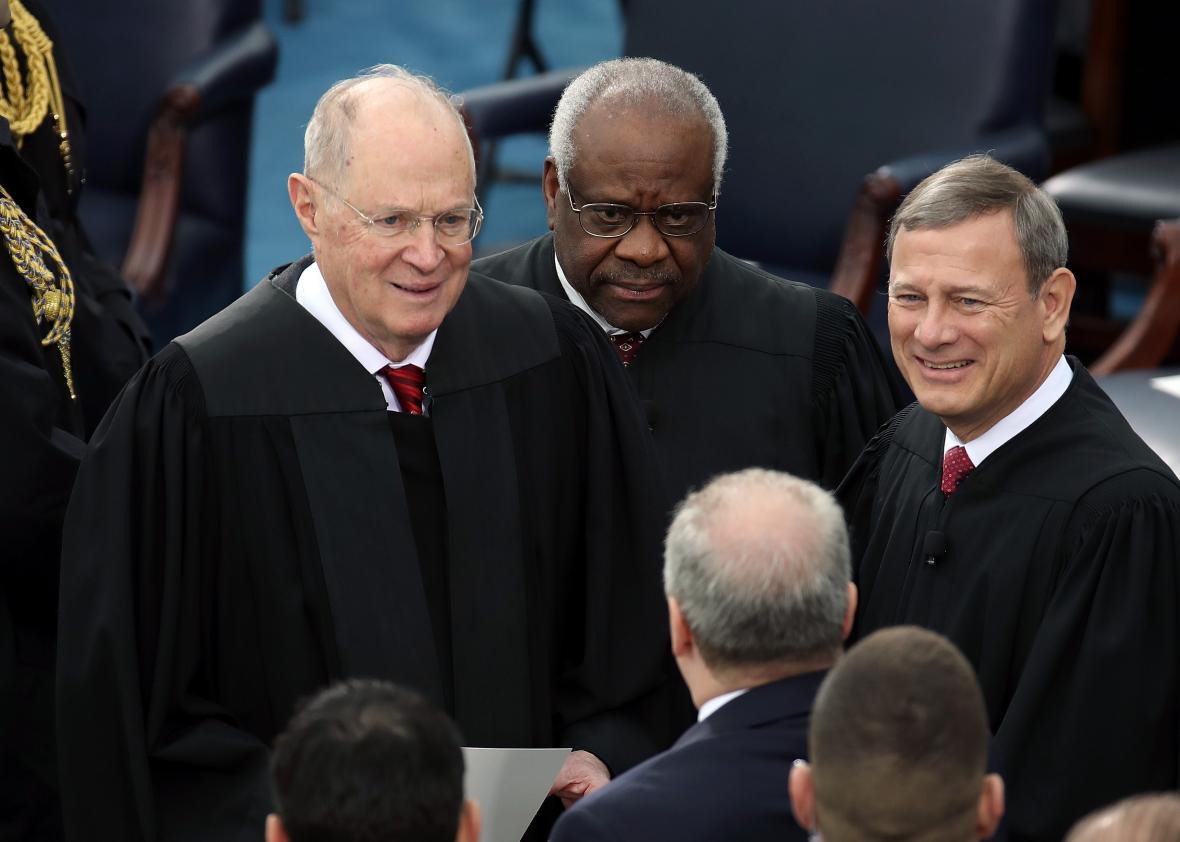

These are the words of an “evolved” Kennedy, a justice who has, in his later years, developed a clear-eyed pragmatism about racial discrimination that distinguishes him from his conservative brethren. It’s disappointing that Chief Justice John Roberts did not join him in this eloquent rebuke to racism. While Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito remain willfully blind to race discrimination, Roberts has recently shown flickers of awareness, occasionally acknowledging blatant racial bias in our criminal justice system. Unfortunately, Peña-Rodriguez proved a bridge too far for Roberts, who still has more evolving to do before he joins Kennedy in vindicating the Constitution’s clear command of equal dignity for all.