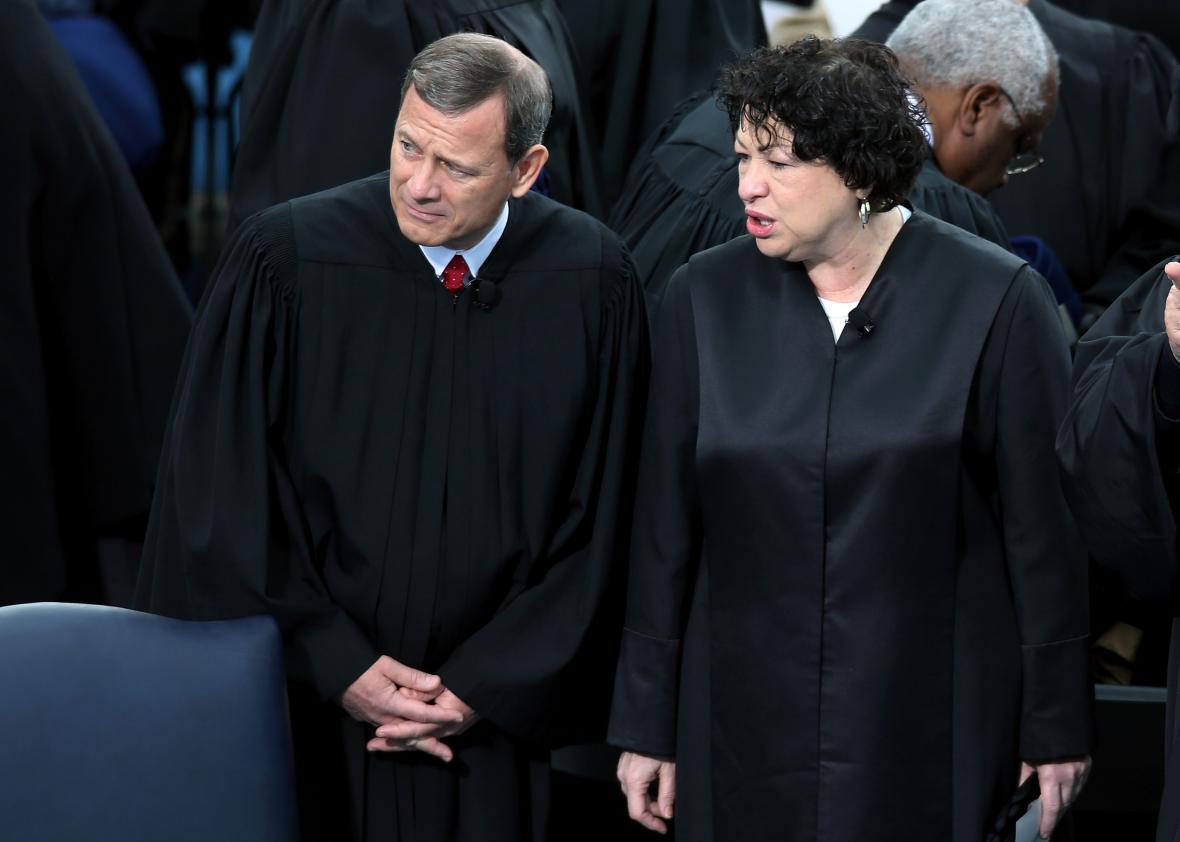

On Wednesday, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of a black death row inmate, Duane Buck, whose own attorney called an “expert” to the stand who told the jury Buck’s race made him a danger to society. Chief Justice John Roberts penned the 6–2 decision holding that Buck received ineffective assistance of counsel in violation of the Sixth Amendment, and allowing him to appeal his capital sentence. Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito dissented.

Buck was convicted of capital murder in Texas, a conviction which carries with it the possibility of a death sentence. At the penalty phase of the trial, which took place in 1997, the jury was told it could impose the death penalty if it found “a probability that the defendant would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society.” Buck’s attorney called an expert, Dr. Walter Quijano, to testify—with the knowledge that Quijano believed Buck’s race increased his probability of future violence. Sure enough, on the stand, Quijano testified that Buck’s race was “know[n] to predict future dangerousness.” He added, “It’s a sad commentary that minorities, Hispanics, and black people are overrepresented in the criminal justice system.”

Unsurprisingly, the jury sentenced Buck to death. He appealed—without raising an ineffective assistance of counsel claim—and a state court affirmed his sentence. He then filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus, which, bizarrely, did not mention Quijano’s racism. Not long after, then-Texas Attorney General John Cornyn discovered that Quijano had given blatantly racist testimony in multiple cases. In 2000, his office sent a notice confessing this error to attorneys for six defendants, including Buck, whose sentencing was tainted by Quijano’s testimony. Five of those defendants raised claims in federal court and Cornyn consented to their resentencing. The odd man out was Duane Buck. His attorney filed a second habeas petition raising an ineffective assistance of counsel claim, but he filed it in state rather than federal court. In Buck’s case, Cornyn decided not to confess error or to consent to resentencing, asserting that his situation was different because his own attorney called Quijano rather than the state. Ultimately, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals tossed out Buck’s claim because he didn’t raise it in his first habeas petition.

At this point, Buck’s case had entered what Roberts describes as “a labyrinth of state and federal collateral review, where it has wandered for the better part of two decades.” Buck’s plea before the Supreme Court was essentially to be released from this labyrinth. If the court determined that Quijano’s testimony created “extraordinary circumstances,” it could set aside past procedural errors and allow him to pursue his ineffective assistance of counsel claims on appeal. In short, Buck wanted the court to agree that the injustice he suffered was so egregious that he deserved to raise it on appeal, even if the rules would usually forbid it.

And the court did just that. As Roberts explained, “a defendant who claims to have been denied effective assistance must show both that counsel performed deficiently and that counsel’s deficient performance caused him prejudice.” And Buck satisfied both prongs of this test. First, his attorney clearly performed atrociously, given that it’s difficult to think of a worse idea than calling an expert to testify that your client’s race makes him more dangerous. Second, Quijano’s testimony very likely prejudiced the jury against Buck. Elaborating on this point, Roberts is at his race-blind best:

Dr. Quijano’s testimony appealed to a powerful racial stereotype—that of black men as “violence prone.” In combination with the substance of the jury’s inquiry, this created something of a perfect storm. Dr. Quijano’s opinion coincided precisely with a particularly noxious strain of racial prejudice, which itself coincided precisely with the central question at sentencing. The effect of this unusual confluence of factors was to provide support for making a decision on life or death on the basis of race. …

[T]his is a disturbing departure from a basic premise of our criminal justice system: Our law punishes people for what they do, not who they are. Dispensing punishment on the basis of an immutable characteristic flatly contravenes this guiding principle.

In sum, this Sixth Amendment violation presented the kind of “extraordinary circumstances” that allow Buck to hop over procedural roadblocks and pursue his claim on appeal.

Roberts’ decision in favor of Buck has a lot in common with his celebrated opinion last year in Foster v. Chatman, another case of blatant racism in the criminal justice system. While the chief justice can be naïvely and obnoxiously blind to racism, he is at least willing to confront the most appalling examples when they stare him in the face. Here, Roberts simply could not ignore the obvious unfairness of Buck’s situation. If only his racial sensitivity extended to those state laws motivated by racism but dressed up in the flimsiest of pretexts.