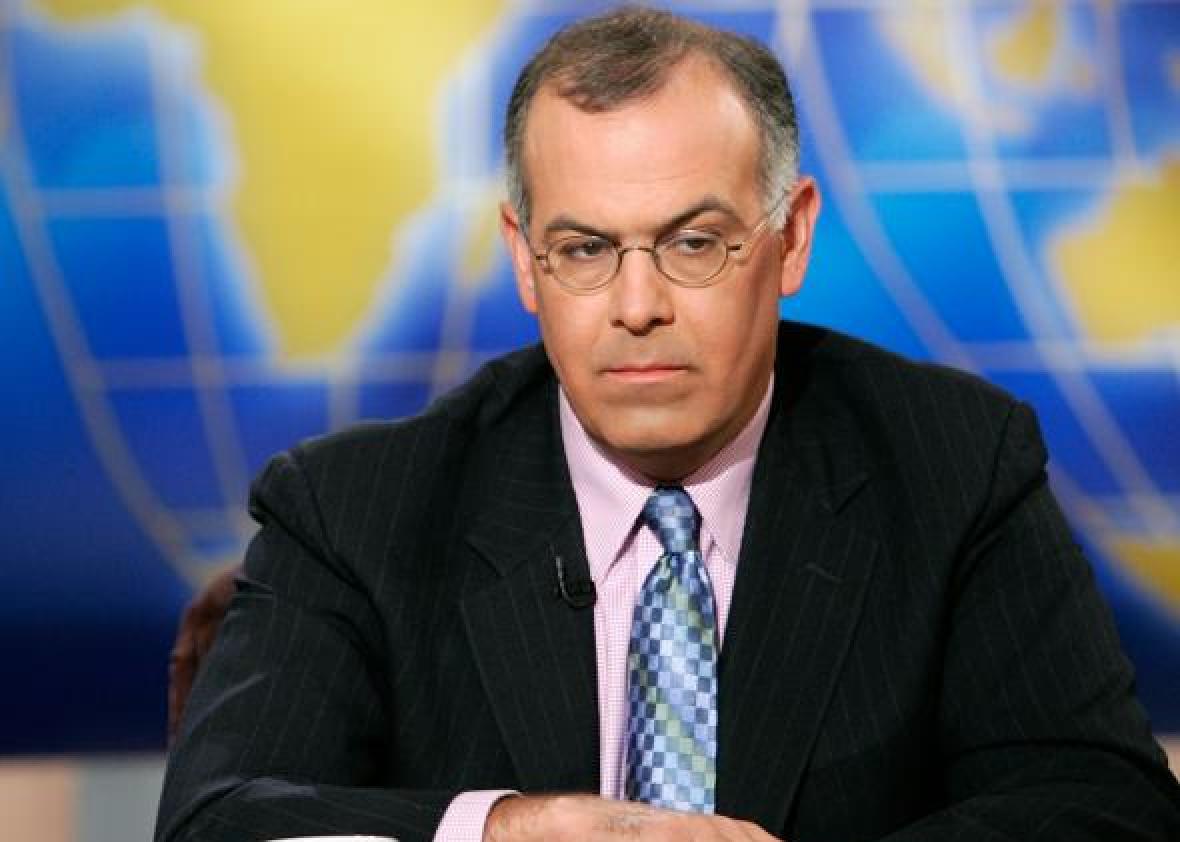

Alex Wong/Getty Images for Meet the Press

New York Times columnist David Brooks, who is to genuine intellectual inquiry as Flintstones vitamins are to the polio vaccine, filed a column Tuesday about the weekend’s spectacularly well-attended anti-Trump women’s marches. And there must have been some sort of mistake at Times HQ, because they put his column in the newspaper even though it belongs at the bottom of a well.

Let’s go through it. This is Brooks’ thesis.

These marches can never be an effective opposition to Donald Trump.

No one said they were. There are articles all over the internet written by and about progressives who acknowledge that the marches were only a first step (har) in the long process of organization required to achieve political and policy success.

We’re off to a bad start. Next:

In the first place, this movement focuses on the wrong issues. Of course, many marchers came with broad anti-Trump agendas, but they were marching under the conventional structure in which the central issues were clear. As The Washington Post reported, they were “reproductive rights, equal pay, affordable health care, action on climate change.”

These are all important matters, and they tend to be voting issues for many upper-middle-class voters in university towns and coastal cities. But this is 2017. Ethnic populism is rising around the world. The crucial problems today concern the way technology and globalization are decimating jobs and tearing the social fabric; the way migration is redefining nation-states; the way the post-World War II order is increasingly being rejected as a means to keep the peace.

When I read those paragraphs, I spit my latte all over my Volvo. In what sense are “affordable health care” and “action on climate change” not related to “technology and globalization”? Like, directly related in a manner that would be condescending to even explain out loud? Since when has “affordable health care,” which in the form of Medicare is perhaps the quintessential meat-and-potatoes issue in American politics, been a pet cause of “upper-middle-class voters in university towns and coastal cities?” And could he truly be suggesting that the marches would have been more broadly popular and meaningful if organizers had announced that their primary concerns would be the redefinition of nation-states and the deterioration of the post–World War II international security regime?

More:

All the big things that were once taken for granted are now under assault: globalization, capitalism, adherence to the Constitution, the American-led global order. If you’re not engaging these issues first, you’re not going to be in the main arena of national life.

If you can’t understand how a protest against Donald Trump’s presidency and for affordable health care, action on climate change, and the protection of Roe v. Wade (which has been threatened by the unprecedented refusal to confirm Merrick Garland) is not “engaging” with “globalization,” “capitalism,” and “adherence to the Constitution,” then … bleh.

Next there’s some classic conservative-intellectual whining about the ’60s—assertions that protest is merely “mass therapy” and a “seductive substitute for action.” Brooks writes pejoratively that protest-based movements appeal to “mere feeling” in our “age of expressive individualism” and that marches lack the political efficacy of “run[ning] for office, amass[ing] coalitions of interest groups,” and “engag[ing] in the messy practice of politics.”

In reality, the women’s marches were organized by a number of full-time political activists and sponsored by groups whose very purpose is to attain political influence. They involved speeches by prominent female elected officials (e.g. Elizabeth Warren) and other female public figures familiar with the nuts and bolts of electoral politics (e.g. Planned Parenthood’s Cecile Richards). And the day after the march, EMILY’s List—an interest group—held a seminar, attended by an estimated 500 women, about the process of running for office.

Moving on:

Finally, identity politics is too small for this moment. On Friday, Trump offered a version of unabashed populist nationalism. On Saturday, the anti-Trump forces could have offered a red, white and blue alternative patriotism, a modern, forward-looking patriotism based on pluralism, dynamism, growth, racial and gender equality and global engagement.

Instead, the marches offered the pink hats, an anti-Trump movement built, oddly, around Planned Parenthood, and lots of signs with the word “pussy” in them.

For one, Brooks just gets done complaining that “marches” don’t engage closely enough with interest groups when he begins to complain that this march engaged too closely with “identity politics” and Planned Parenthood. For another, his description of what the march should have “offered”—a patriotic appeal to pluralism—is, as far as I can tell, actually a totally on-point description of what it did offer and why people who participated in it felt good about what they were doing. Look at this video of a massive cheer spreading across an unfathomably large gathering of Americans on and around the National Mall and tell me that it doesn’t represent dynamic modern patriotism. (Also, there is the white-myopic irony of claiming, in a column published four days after the inauguration of a president advised and supported by actual white nationalists, that “identity-based political movements” can’t succeed.)

Finally, Brooks writes that the “central challenge” of the progressive movement shouldn’t be to “celebrate difference” or seek social justice for the disadvantaged (which he sees more or less as large-scale efforts to give everyone their own preschool-style special snowflake sticker) but to “rebind a functioning polity and to modernize a binding American idea”—a slogan that is sure to resonate with everyday heartland Americans. Brooks concludes astoundingly—in a column that, to reiterate, denigrates the idea of affordable health care as the silly hobby of foo-foo rosé quaffers—that the ideal model for a lasting anti-Trump political movement is in fact presented by Hamilton. The Broadway musical that costs one jillion dollars to see.

I swear. I swear! Look here for yourself.

David Brooks is an affluent East Coast white-collar professional who’s made it his mission to mansplain the concerns and beliefs of heartland Americans to other East Coast white-collar professionals using the language of history and political philosophy. But as far as I can tell Brooks only lived in Middle America during college at the University of Chicago and for two years thereafter—and his understanding of history, political philosophy, and American public opinion doesn’t appear to have advanced since he was an undergraduate.* Lacking the personal, reportorial, or academic experience that would be required for actual insight into our changing country, he thus remains a devotee of the “Middle Americans are actually McCain/Lieberman centrists” Serious Frowny-Face Beltway Guy school of thought that has had no basis in empirical reality since at least the dawn of the millennium. And there may be no more precise distillation of this problem than a column that presumes to tell the successful organizers of one of the largest protests in U.S. history that the real way to build a national movement of regular people is to listen to the Hamilton soundtrack.

I don’t want to suggest there’s anything terribly wrong or unusual about being a centrist East Coast white-collar professional. If the entire Republican Party consisted of such people, the country would be in a better place. But the New York Times, given its reach and influence, shouldn’t be giving its readers the impression that someone with David Brooks’ viewpoint has relevant insight into what does and doesn’t work in modern American politics. There’s no particular reason aside from name recognition that the Times should continue to give him a platform to misinterpret current events through the niche lens of his own small-ish tribe.

*Correction, Jan. 24, 2017: This post originally misstated that Brooks only lived in “Middle America” during college. He also lived in Chicago for approximately two years after graduating.