The 1948 Italian election was supposed to be a nail-biter, and one with potentially major consequences in the early days of the Cold War. Back then, Italy had one of the strongest communist parties in Western Europe, which relied on Soviet financial assistance, and the Americans’ recently established Central Intelligence Agency worried that the reds were about to establish a beachhead in what a memo to the White House described as “the most ancient seat of Western culture.”

Acting under a secret National Security Council directive without authorization from Congress, the CIA set to work, using its assets in the Italian secret service and diverting funds meant for the postwar reconstruction of Europe to newly formed political fronts, anti-communist Italian politicians, and Catholic groups. The Christian Democratic Party ended up winning by a comfortable margin. Whether this would have happened anyway without U.S. help is open to debate, but as Tim Weiner writes in his history of the CIA, Legacy of Ashes, the agency was encouraged by the victory and “the CIA’s practice of purchasing elections and politicians with bags of cash was repeated in Italy—and in many other nations—for the next twenty-five years.”

A little more than two weeks until Inauguration Day, and the incoming administration continues to dismiss, even just this morning, allegations that Russia deliberately interfered in the 2016 U.S. election by hacking and leaking information from Hillary Clinton’s campaign. But interference by either Moscow or Washington in other countries’ elections isn’t unusual at all. A recent paper by Dov Levin, a postdoctoral fellow at Carnegie Mellon University’s Institute for Politics and Strategy, shows just how common it’s been.

Using declassified documents, statements by officials, and journalistic accounts, Levin has found evidence of interference by either the United States or the Soviet Union/Russia in 117 elections around the world between 1946 and 2000, or 11.3 percent of the 937 competitive national-level elections held during this period. Eighty-one of those interventions were by the U.S. while 36 were by the USSR/Russia. They happened in every region of the world, though most commonly in Europe and Latin America. The two powers tended to focus on different countries, though Italy was a favorite of both, receiving eight interventions by the U.S. and four by the Soviets.

Not all these interventions relied on methods as crude as bags of cash, though many did. Others included training locals of the preferred side in campaign techniques, covertly disseminating damaging information or disinformation about the other side, or providing or withdrawing foreign aid to influence the vote. Levin has found that interventions on average correlate with an increase in the vote of the preferred side of 3 percent, enough to swing a close race.

The U.S. and Russia aren’t the only countries that do this. China has interfered in several Taiwanese elections, for instance, and the late President Hugo Chávez of Venezuela gave support to several preferred candidates throughout Latin America, but Levin said in an email that “from the available evidence that I currently have, the U.S. and the Soviet Union/Russia have been the most frequent performers of partisan electoral interventions since World War II.”

Interventions have become less common since the end of the Cold War, and the methods most commonly used have also changed. “From the available evidence, since the end of the Cold War the CIA is indeed far less involved in such operations than it used to be during the Cold War era (although there is some evidence that it was involved in at least one such electoral intervention in a competitive Iraqi election after our regime change operation there in 2003),” Levin told me. “Nevertheless, some covert partisan electoral interventions continue to be done by other U.S. government bodies.”

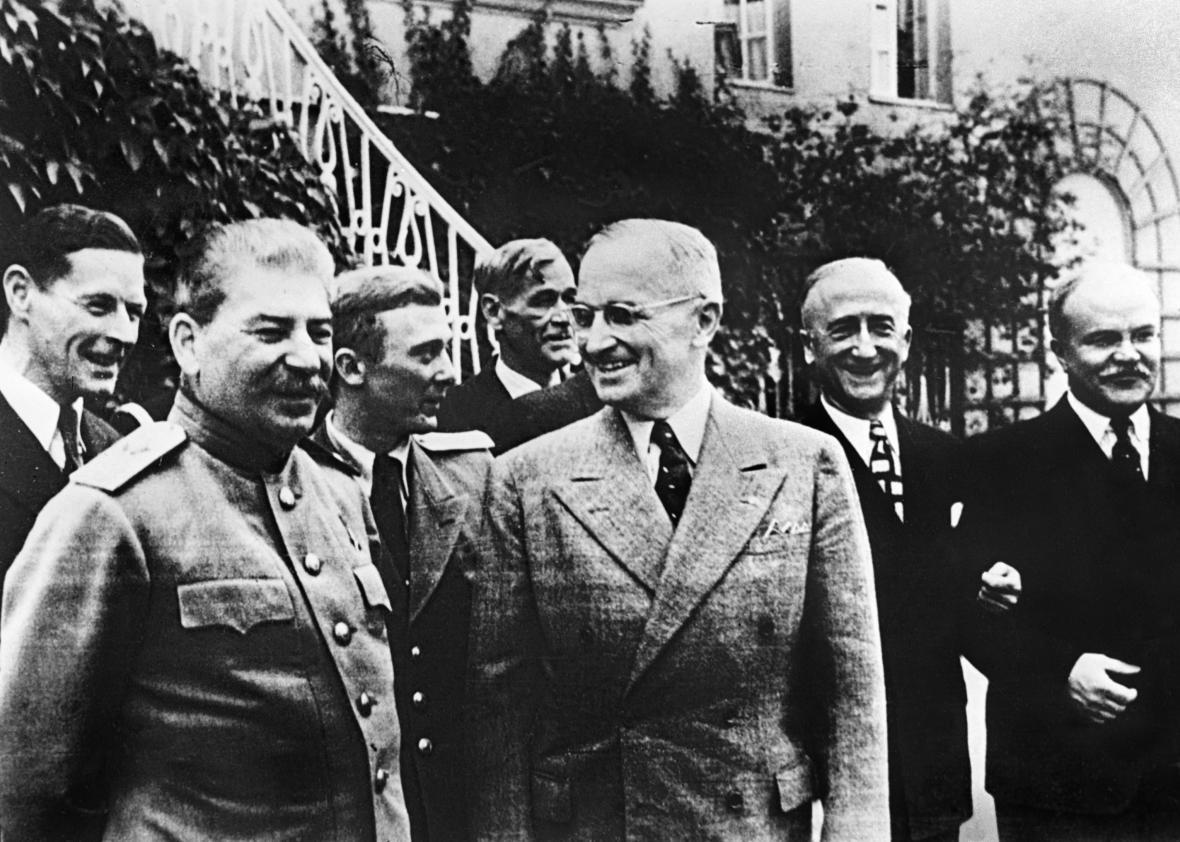

And obviously, there’s evidence that Russia is still trying to tip the electoral scales around the world as well, not just in the U.S. but in several European countries too. Levin also notes that 2016 would be the third case of meddling by Moscow in a U.S. election: the Soviets intervened against Harry Truman in 1948 and Ronald Reagan in 1984, though both of those presidents won re-election anyway.

With U.S.-Russia relations at a new post–Cold War low, these interventions may become more common yet again—though the big question now is how a new administration will impact that relationship. Regardless, while computer hacking has added a new tool to the election meddlers’ arsenal, the basic playbook has been well-established for years.