On Tuesday, Californians were asked to determine the fate of the death penalty in their state through two contrasting ballot measures: One proposed ending capital punishment altogether; the other proposed speeding up executions. They rejected the former and chose the latter, creating a very real chance that innocent people will soon be executed in California.

Proposition 62, which would have repealed the death penalty and replaced it with life in prison without parole, received just 46.1 percent of the vote. But Proposition 66, the purported “reform” measure, won 50.9 percent of the vote, just above the threshold for victory. I put “reform” in scare quotes because the alleged reforms that the measure will institute are pretty terrifying. Its goal is to speed up executions—California hasn’t had one since 2006—by, in effect, making it harder for death row inmates (of whom there are nearly 750) to prove their innocence. Prop 66 would force courts to conclude inmates’ appeals process in five years, when it typically drags on for decades. It attempts to do so by directing appeals back to the trial court, rather than to the state Supreme Court, where these appeals currently go.

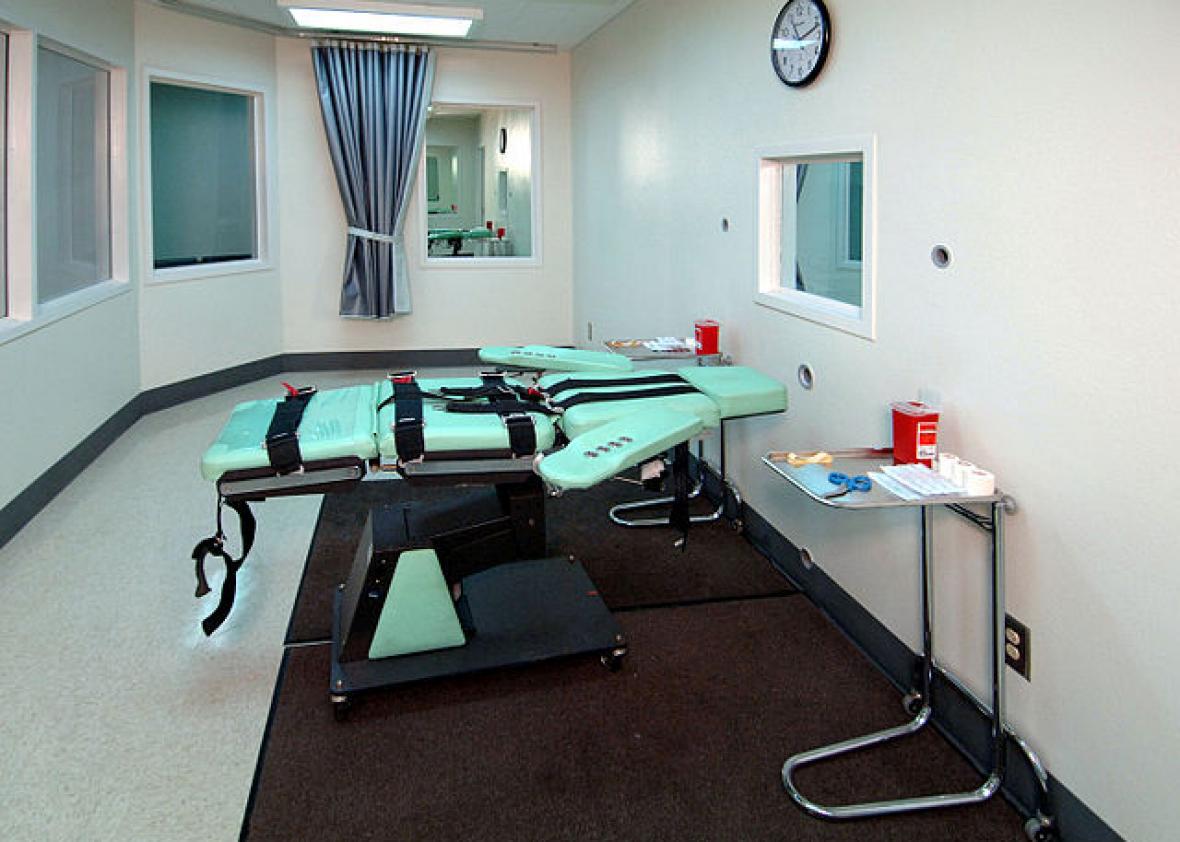

But in most cases, trial court will be the same court that allegedly committed the original error. Few judges are willing to acknowledge that they messed up, so almost all these petitions will be denied. At that point, the inmate still has a right to appeal the trial court’s determination, further drawing out the process. Prop 66 will also move death row inmates from their current location in San Quentin to prisons across the state. That will be devastating for many prisoners, who have come to rely on the Habeas Corpus Resource Center near San Quentin to help process their appeals. These attorneys will now have to drive many hours across the state to see their clients. Moreover, the measure limits prisoners’ ability to sue the state to determine whether its lethal injection protocol meets constitutional requirements. Given how often the secret chemicals used in lethal injection turn execution into torture, this feature simply seems cruel.

Prop 66 attempts to address the shortage of death penalty lawyers by commandeering state appellate attorneys to work on more capital appeals. Inevitably, this expropriation will result in unmotivated lawyers with no knowledge of the capital appeals process providing clients with subpar representation. The system created by Prop 66 seems destined for failure—and even if it works, it presents a huge risk of wrongful executions. One in 10 capital sentences in California gets overturned, and three inmates on California’s death row have been exonerated. There may well be more innocent men awaiting execution in San Quentin. Prop 66 will make it harder for them to prove their innocence before an impartial judge and receive effective assistance of counsel.

Had California instead voted to shutter death row, it would have saved $170 million each year. Instead, it is altering its capital system to mimic that of Texas—which has killed at least three innocent people—and adopting a style of reform that failed in Colorado. Prop 66 may indeed end California’s moratorium on executions. But it does nothing to ensure that the men put to death are actually guilty of the heinous crimes with which they’ve been accused.