Until last weekend, there was an obvious front-runner for this year’s Nobel Peace Prize, which will be announced on Friday morning. The peace deal negotiated by Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos and FARC leader Rodrigo “Timochenko” Londoño would have brought an end to one of the world’s longest running conflicts. But Colombian voters’ surprising rejection of that deal on Sunday has thrown things into disarray, including the peace prize field.

The Nobel Prize is notoriously difficult to predict, and only getting trickier with a record 376 nominated candidates this year, including both individuals and organizations. The full list is not published, though many of the names on it leak out. Some—Chinese President Xi Jinping, Susan Sarandon, and, yes, Donald J. Trump—we can rule out right away. A few of the much-hyped names also seem pretty unlikely. If Pope Francis was going to get it, it should have been last year, when his advocacy on issues like the refugee crisis and climate change felt more novel and less futile. A peace prize for German Chancellor Angela Merkel would enrage many in Germany, including, probably Angela Merkel, and I doubt they want a repeat of the Barack Obama experience.

But somebody is going to win it. Drawing on an unofficial but widely cited shortlist compiled every year by the Peace Research Institute Oslo, the betting odds at Paddy Power, and my own baseless speculation (which proved prescient when the Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet won last year), here’s a look at this year’s front-runners.

Syria Civil Defense (The White Helmets)

The volunteers who provide first aid and pull victims out of the rubble in cities like Aleppo are the closest thing the complex and dismal war in Syria has to unambiguous good guys. Giving them the prize would highlight the urgency of the ongoing crisis facing civilians there. The White Helmets are leading the betting markets and have been getting a lot of publicity of late, including a new documentary and a public letter backing their candidacy from Hollywood humanitarians including George Clooney and Ben Affleck. But not everyone’s a fan: Russia and the Syrian regime, as well as some “anti-imperialists” in the west, paint the partially U.S.-funded group as agents of regime change. Still, this would probably be the most popular choice with the public. The smart money is on them right now. (Don’t put money on the Nobel Peace Prize. It’s tacky and also you will almost definitely lose.)

Svetlana Gannushkina

A prize for Gannushkina, who’s PRIO director Kristian Berg Harpviken’s top pick to win this year, would highlight two important issues: human rights in Russia and the global refugee crisis. A veteran civil society activist in Russia and founder of the human rights group Memorial, Gannushkina has also worked to provide aid and education to migrants and refugees. She’s been shortlisted before and was one of the winners of this year’s Right Livelihood award, often called the “alternative Nobel.”

Greek Islanders

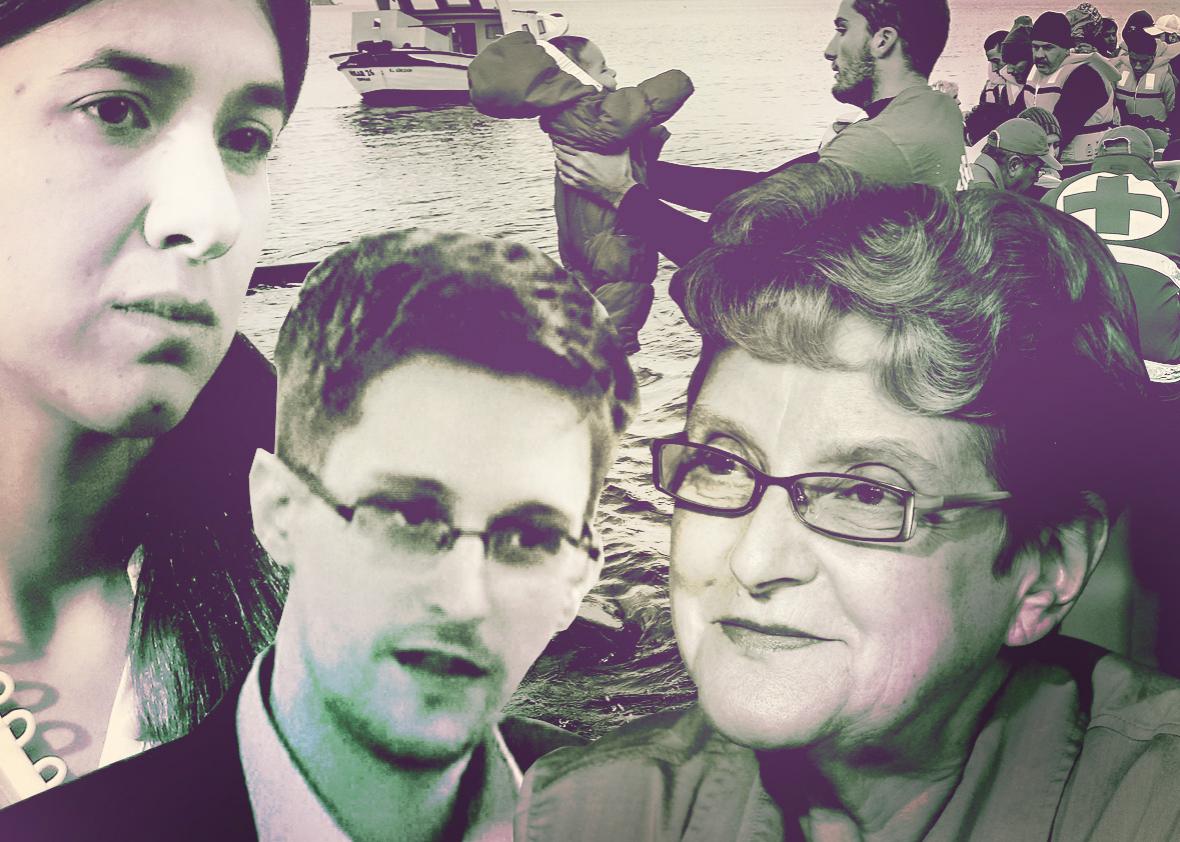

There’s been widespread speculation that this year’s prize might go to the residents of Greek islands like Lesbos, who have volunteered to help the refugees and migrants washing up near their homes. These are people faced with both the brunt of a massive humanitarian crisis and the economic collapse of their own government. The Nobel committee only gives the award to specific people and organizations, but a few individuals, including Emilia Kavisi, an 85-year-old grandmother photographed bottle-feeding a Syrian baby, and fisherman Stratis Valiamos who rescued dozens of refugees from drowning in his boat, have been suggested as symbolic representatives of the group.

Nadia Murad

Murad, an ethnic Yazidi and former student from Northern Iraq, was kidnapped and held as a sex slave by ISIS for three months before escaping in November 2014. She has since become one of the most high-profile advocates for the Yazidis, a religious minority targeted for extermination by ISIS, and outspoken about the group’s systematic use of rape. She was appointed as a U.N. goodwill ambassador last month.

Ernest Moniz and Ali Akbar Salehi

Last year, there was a lot of speculation that John Kerry and Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif could share the prize for their work negotiating the Iran nuclear deal. The recent tragedy of errors in Syria makes that a lot less likely, but the two former nuclear scientists—the U.S. secretary of energy and the head of Iran’s Atomic Energy Organization—who worked out much of the technical nitty-gritty of the deal, might still have a shot. It would be a win for science diplomacy.

Edward Snowden

Snowden is nominated every year and is usually considered too hot to handle, but Harpviken thinks this might be his year. The USA Freedom Act passage last year, as well as recent revelations about government email surveillance, have provided some vindication for the controversial exiled whistleblower. The EU parliament passed a bill calling on member states to prevent his extradition to the United States last year, but it’s still not clear if he would be able to travel to Norway to pick up the award. There have been absentee winners before, but this could be the first ever webcam acceptance speech.

Denis Mukwege

This Congolese gynecologist, who has treated thousands of victims of sexual assault during his country’s years of conflict and civil war, is another perennial nominee whose recognition would be long overdue.

Raif Badawi

On the one hand, it would be great for the Norwegian Nobel Committee to highlight free speech, internet freedom, and the deplorable human rights situation in Saudi Arabia by giving the award to this Saudi blogger, who was sentenced to 10 years in prison and 1,000 lashes on charges of apostasy and insulting Islam. On the other hand, the publicity that comes with a Nobel hasn’t always been all that helpful for those imprisoned by authoritarian governments. Aung San Suu Kyi, for instance, spent another nine years under house arrest in Myanmar after winning the prize in 1991. And 2010 winner Liu Xiaobo remains locked in a Chinese jail.

The Marshall Islands

The committee highlighted efforts to prevent nuclear war in 1985, 1995, and 2005. They missed their 10-year-cycle last year, but recent events on the Korean peninsula and rising tensions between the United States and Russia make the issue much more timely. A number of possible candidates to fill this slot have been mentioned this year, including the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons and the Nuclear Peace Foundation. But most intriguing to me is the Marshall Islands, the tiny Pacific nation and site of the U.S. nuclear tests in the 1940s and ‘50s that has filed lawsuits against the world’s nine nuclear powers for failing to live up to their commitments to eliminate nuclear weapons on the Non-Proliferation Treaty. The Hague-based International Court of Justice threw out the suit against three of the countries (the U.K., India, and Pakistan) this week, but a Nobel would be a deserved consolation prize for an effort that was mainly a (worthy) publicity stunt. Former Marshallese foreign minister Tony deBrum and the government’s legal team have both been nominated for their work on the suit.

Victims of the Colombian Conflict

The conventional wisdom from Harpviken and others is that Colombia’s negotiators are out of the running after this week’s setback. But Nobel Prizes often reflect aspirations for peace rather than past accomplishments (see: Obama, Barack). If the committee had been planning to recognize peacemaking in Colombia, perhaps they could just scrap the awards for Santos and Timochenko and recognize some of the groups of victims who have organized to push for a peaceful settlement of the conflict and participated in the negotiations. I don’t see why we shouldn’t recognize those working for peace, even if their leaders, and many of their citizens, couldn’t quite get the job done.