California Gov. Jerry Brown signed a law on Saturday requiring entertainment websites like IMDB to remove an actor’s age or birthdate upon request. The purpose of the statute is to prevent age discrimination in casting—a noble goal made even more appealing politically by a very expensive Screen Actors Guild lobbying campaign. One small problem, though: The law is obviously, blatantly, indeed almost comically unconstitutional.

Where to begin? Well, the measure, called AB1687, is, on its face, a suppression of speech. Entertainment websites designed to present information to both professionals and the general public are now subject to a very specific gag order: If a subscriber demands that the website remove his or her age, the site is legally required to comply. (The law applies to all entertainment professionals but is designed to shield actors in particular from discrimination.) That is called censorship, and the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment generally prohibits it.

California claims that AB1687 doesn’t run afoul of the First Amendment because, as Majority Leader Ian Calderon told the Hollywood Reporter, it’s merely “a regulation of commercial speech.” Commercial speech is expression used to sell or promote a product for profit, and it does indeed receive lesser, though still fairly robust, First Amendment protections. Calderon believes AB1687’s restrictions can be rounded down to “commercial speech” because only subscribers to an entertainment website can demand the removal of their age or birthdate.

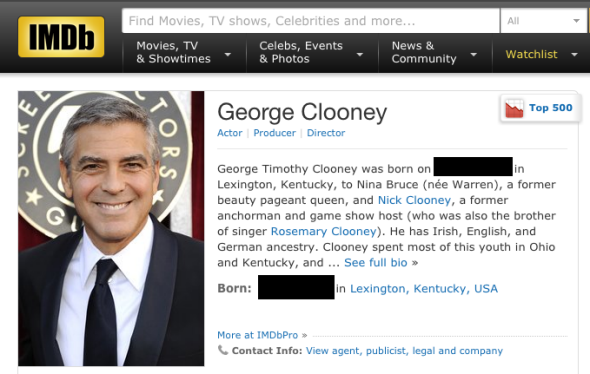

But Calderon is wrong: The speech that AB1687 suppresses is not exclusively commercial. IMDB (and similar websites) may be linked to commerce—subscribers use them for casting purposes—but that doesn’t automatically render their speech “commercial,” as Calderon asserts. At bottom, IMDB remains an information database, open to both industry professionals and the public at large, designed not only to sell a service but also to gather and convey facts. And information databases, from encyclopedias to search engines, receive full First Amendment protections—not the diminished protections provided to commercial expression.

AB1687, then, isn’t subject to the judicial test governing commercial speech. Rather, it’s subject to strict scrutiny, because it restricts truthful, noncommercial information by functioning as a classic content-based regulation of expression—targeting speech based on its “communicative content” (that is, an individual’s age). Thus, AB1687 must be “narrowly tailored to serve compelling state interests.” Preventing age discrimination is surely a compelling state interest—but is AB1687 really “narrowly tailored” for that purpose? One rule of narrow tailoring is that a regulation of speech may be neither too broad nor too narrow. If a law is too broad (or “overinclusive”), it sweeps in more speech than necessary to promote the compelling interest; if it’s too narrow (or “underinclusive”), it doesn’t sufficiently advance that interest, because it leaves equally problematic speech untouched.

California’s new law is a textbook example of a fatally underinclusive speech regulation. AB1687 applies only to any “commercial online entertainment employment service,” which the bill defines broadly. But it leaves out the myriad other mediums that could convey an entertainment professional’s age, from a gossip column to a blog post to Wikipedia. As the Supreme Court explained in 2011, this kind of underinclusiveness “raises serious doubts about whether the government is in fact pursuing the interest it invokes, rather than disfavoring a particular speaker or viewpoint.” With AB1687, California looks to be specifically targeting IMDB and its ilk for daring to provide (truthful) information about age—not seriously striving to scrub entertainment professionals’ age from the public record.

Underinclusiveness is enough to defeat a content-based speech restriction, and that is likely what will defeat AB1687. We shouldn’t mourn its inevitable downfall. As web freedom lobbyist Michael Beckerman has explained, AB1687 is not just unconstitutional: It is dangerous, an embodiment of the idea that the government can promote equality by simply suppressing expression, rather than addressing the root causes of discrimination. “Availability of information does not cause discrimination,” Beckerman wrote; “human bias does.” That’s exactly right. From stringent enforcement of existing law to stiff penalties for wrongdoers, California has plenty of tools at hand to curb age discrimination in the entertainment industry. Censorship is not one of them.