It’s official: The week of the Republican National Convention has been a terrific week for voting rights in the United States. Not because of the RNC—the GOP platform explicitly endorses voter suppression laws—but because federal courts across the country have struck down state measures designed to make voting harder for minorities. First, a federal judge found that Wisconsin’s stringent voter ID laws placed an undue burden on many citizens’ fundamental right to vote; then an appeals court found that Texas’ even more draconian voter ID law had a discriminatory effect on minority communities in violation of the Voting Rights Act. Now a federal judge in Michigan has invalidated the state’s ban on straight-party voting, finding that the law violates both the Voting Rights Act and the United States Constitution.

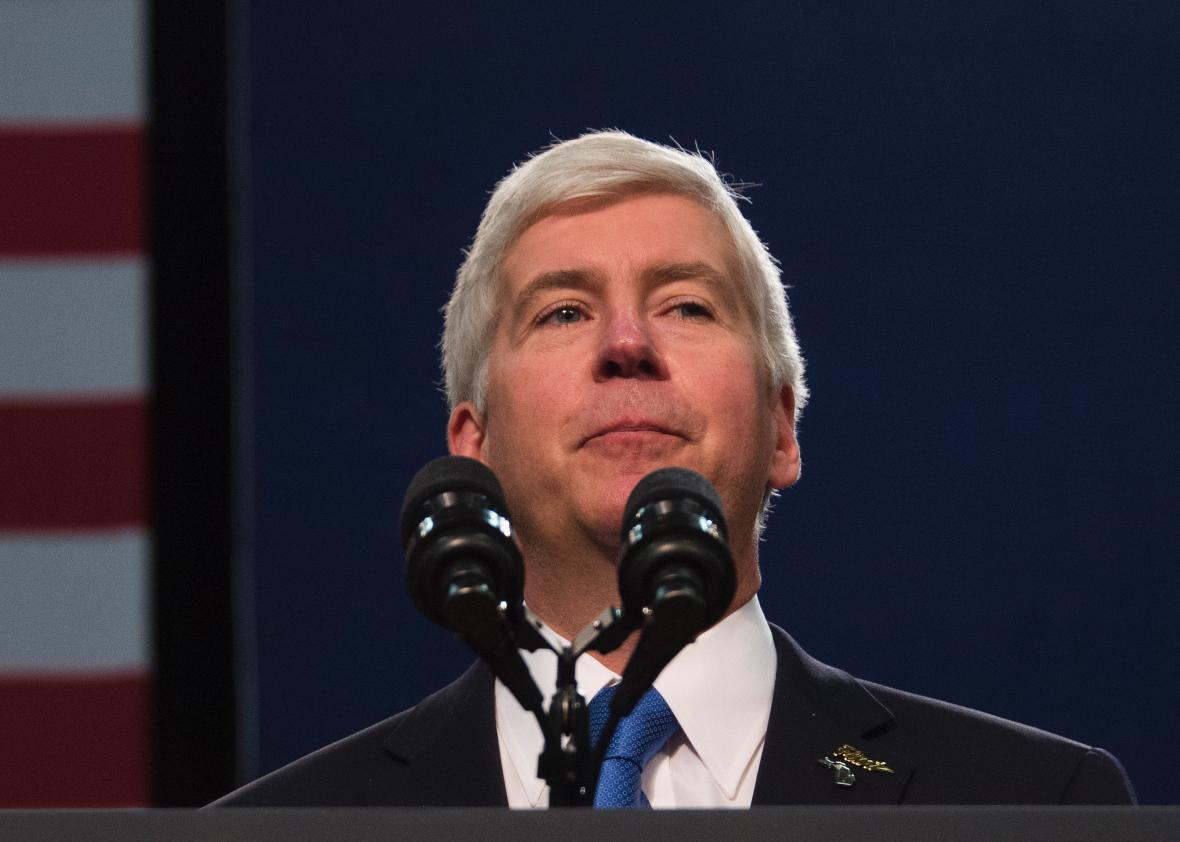

Michigan only outlawed straight-party voting—which allows a voter to cast his or her ballot for every candidate of a specific party all at once—in 2016. Republicans spearheaded the effort to ban the practice, asserting that citizens should vote for “individual people” instead of parties. “It’s time to choose people over politics,” Republican Gov. Rick Snyder said while signing the bill, P.A. 268, into law.

What Snyder didn’t mention was that black voters disproportionately use straight-party voting—and that eliminating straight-party voting will indisputably lengthen the voting process, leading to long lines at the polls in black communities. Citing this fact, U.S. District Judge Gershwin A. Drain writes that P.A. 268 “presents a disproportionate burden on African Americans’ right to vote,” in violation of the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. “[T]here are “extremely high” correlations between the size of the African-American voting population within a district, and the use of straight-party voting in that district,” Drain explains. Thus, “the elimination of straight-party voting would likely have a larger impact on African-American voters” in violation of the Constitution. (Black voters seem to prefer straight-party voting because they vote Democrat more consistently than almost any other group.)

This impact, Drain concedes, might be justifiable if the state had a good reason for banning straight-party voting. It emphatically did not. In court filings, the state argued that the prohibition was necessary to “preserve the purity of elections,” “to guard against abuses of the elective franchise,” and to ensure that voters are truly “engaged” in the electoral process. But “[t]hese interests are tenuous at best,” Drain asserts. Michigan

has not demonstrated how straight-party voting has damaged, or could possibly damage, the “purity” of the election process. There is nothing “impure” or “disengaged” about choosing to vote for every candidate affiliated with, for example, the Republican Party. A voter may base their vote on any criteria he or she wishes, including party affiliation.

Drain then adds this acid coda:

Moreover, the idea that voting one’s party reflects ignorance or disengagement is, ironically, disconnected from reality. Voters may, and often do, have substantive reasons for voting only for members of certain political parties. Even if “disengaged” voting was problematic—and it is not—the Court finds that P.A. 268 does nothing to encourage voters to be any more “engaged.” … [T]here is nothing in the record to suggest that changing the ballot form will encourage voters to become political science scholars before voting. Therefore, functionally P.A. 268 is “disengaged” from its own justifications.

For good measure, Drain also held that P.A. 268 contravenes the Voting Rights Act of 1965 by reducing black voters’ “opportunity to participate in Michigan’s political process relative to other groups of voters.” Under the VRA, a state voting restriction is illegal if it places a “discriminatory burden” on minorities—which, Drain exhaustively details, P.A. 268 obviously does. Drain also explains why P.A. 268 is “linked to ‘social and historical conditions’ that have or currently produce discrimination against members of the protected class”—a red flag under the VRA:

It’s no secret that racial discrimination in the state of Michigan has had traumatic effects on education, employment and health in the African-American community. Plaintiffs have provided evidence that African-Americans continue to bear the harmful effects of past discrimination. … [T]hese effects, particularly in the employment setting, have made it more difficult for African-Americans to participate in the political process. …

[T]he disproportionate burdens of P.A. 268 are inexorably linked to racially discriminatory employment practices and housing policies that have created deeply segregated communities across Michigan. African-American communities will be impacted harder by P.A. 268 specifically because our metropolitan areas are so racially polarized. The racial polarization of our metropolitan areas can be tied directly to racist policies such as redlining and housing discrimination.

And, in one remarkable section, Drain points out that the current presidential campaign “has been punctuated” with “racial appeals from its candidates,” some of which “have been implicitly ethnocentric.” To illustrate his point, Drain then pulls excerpts from Donald Trump’s most inflammatory speeches. Under the VRA, voting restrictions are especially suspect when “political campaigns have been characterized by overt or subtle racial appeals.” Trump’s calumny of Mexicans, Muslims, and other minorities, Drain suggests, contributes to the inference that P.A. 268 is part of a broader campaign to drive minorities out of the political process. (“This is all in addition to the emergence of the ‘Black Lives Matter’ Movement, and the increased attention to relationships between minority communities and law enforcement,” the judge writes.)

Drain’s broad decision may not survive review at the ideologically divided United States Court of Appeals of the Sixth Circuit. But it is a stunning indictment of straight-party voting bans, which exist in most states and are widely viewed as benign. Not every straight-party voting law necessarily violates the VRA and the Constitution. But as Drain amply demonstrates, their apparent neutrality may well mask an invidious desire to keep minorities out of the voting booth.