Chaos erupted on the floor of the Quicken Loans Arena earlier today when Rep. Steve Womack (R-Ark.), in his capacity as the convention’s deputy permanent chair, called the assembled delegates to a voice vote. The issue at hand: Whether to accept the party rules drawn up last Friday by the RNC rules committee. Last week, the committee successfully fought off the Never Trump movement’s attempt to alter party rules to allow delegates to vote for the candidate of their choice rather than for the candidate to which they were bound by primary and caucus wins, a long-plotted move calculated to draw pledged delegates away from Donald Trump.

After the rules committee rejected Never Trump delegates’ so-called “conscience clause,” pre-convention reports had all but elegized the GOP holdouts, effectively declaring their effort dead on arrival. But the chorus of cheers, jeers, and boos that accompanied Womack’s call for a voice vote momentarily reinvigorated the movement’s malcontents.

The ayes (for adopting the rules) hollered, the nays (against) groused, and Womack basically cupped his hand to his ear and decided the vote “in the opinion of the chair” went for the ayes—in favor of the rules.

The result was a foregone conclusion. Womack was never going to suffer a serious challenge to Trump’s ascendance—he’d already pooh-poohed a roll call vote that would have required delegates to vote individually for or against party rules.

But just how close did the Never Trump nays get? Slate did some detective work to find out.

First, the basics: A voice vote essentially consists of screaming as loud as possible when your preferred faction is called. The chorus of ayes meant a vote for the rules. The cacophony of nays meant a vote against the rules in a last-ditch procedural measure to unseat Trump. Since there’s no way of knowing precisely how many are voting aye or nay, a voice vote is decided subjectively based which side seems louder.

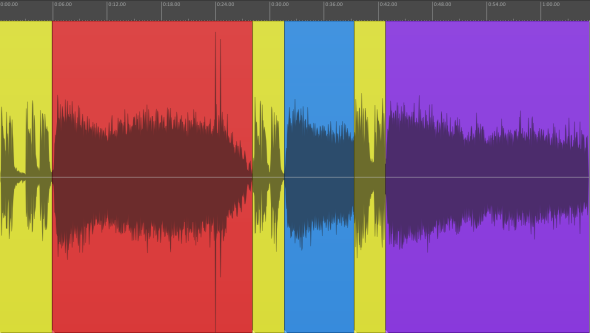

To figure out which bloc really earned the win, Mickey Capper, one of Slate’s podcast producers, ran the audio from the convention through a program called REAPER. The program allowed us to visualize the auditory peaks and troughs that map onto the yells, whoops, and silences of the crowd. Here’s the visual map of the vote that resulted:

Slate

We then color-coded the visual to correspond to who was making noise at any given time. Yellow indicates Womack speaking, red signals those voting in favor of the rules shouting “aye,” and blue telegraphs those voting “nay.” The clip begins with Womack’s call to vote, followed by the sound of the ayes. Womack then calls for the nay vote, after which he pronounces the “ayes” the winners. We also included a fourth category, in purple, that corresponds to the reaction of the crowd after Womack called the vote in favor of the rules. The two outlier spikes that occur about 25 seconds into the minute-long clip represent the sound of Womack’s gavel following the “aye” vote.

Based on our analysis, Womack’s ears weren’t wrong: The “ayes” have it.

But they didn’t win by much. REAPER’s comparison of the volume and loudness of the “aye” and the “nay” votes, both visual and measured in decibels, indicates that the vote was close—very close. REAPER registered a 0.5 decibel difference between the peak of the “aye” vote (which, apart from Womack’s gaveling, was the loudest single moment in the clip and clocked in around -5.6 dB) and the peak of the “nay” vote (approximately -6.1 dB). It also registered about a one-decibel difference in sustained loudness between the two votes, with the “aye” votes taking the cake. (For a more comprehensive and technical explanation of what exactly a decibel is and how in the world they can register as negative values, we direct you here and here).

Mickey interpreted the results of our data to me this way: Even though the “ayes” clearly won, if someone angrily asked you to turn down a too-loud television and you decreased its volume by one decibel, they’d tell you to turn it down again. It’s tough to imagine Womack’s auditory sensitivity was keen enough to detect a substantial difference in volume.

Furthermore, there are other aspects of our audiovisual display that look fishy if Womack’s goal was to appear impartial in calling the vote. It’s clear that Womack allowed the “ayes” to whoop, holler, and exercise in favor of the rules for about 18 seconds—two and a half times as long as he gave nay-voting delegates to do the same. This means Womack cut off “nay” voters before they could enjoy the same second-breath bump in volume that their “aye” counterparts were able to belt out after briefly trailing off around the 12-second mark. Because of the difficulty of picking up on a difference of just one decibel, it’s easy to imagine the question tipping the other way had Womack called for the “nay” vote first.

Nevertheless, the ayes, the RNC rules committee, and, by extension, Trump himself emerged victorious. But only just. The biggest takeaway? Voice voting is a pretty stupid way to figure out anything having to do with who becomes president.