Following his country’s stunning vote to withdraw from the European Union, a triumphant Nigel Farage, leader of the pro-Brexit U.K. Independence Party, proclaimed Thursday night that “a dawn is breaking on an independent United Kingdom.” But thanks to this result, the kingdom may not be united for much longer.

Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said this morning that Scotland sees its future firmly in the EU and that it is “democratically unacceptable” that the country will be removed from the union against its will. “We proved that we are a modern, outward-looking, and inclusive country, and we said clearly that we do not want to leave the European Union,” she said. “I am determined to do what it takes to make sure these aspirations are realized.”

Scots voted 62 to 38 percent against the Brexit on Thursday, with “Remain” winning all 32 council areas in the country. Sturgeon said another referendum on Scottish independence is “highly likely.”

Scotland last held an independence referendum in 2014, voting 55 to 45 percent to remain in the United Kingdom. But that feels like a lifetime ago. Sturgeon’s Scottish National Party has maintained that it would hold another referendum if there were a “significant and material change in the circumstances that prevailed in 2014.” Thursday night’s vote was about as significant a change as you can imagine.

The last time around, EU officials were skeptical about the idea that Scotland could declare independence and simply remain a member state, suggesting that as a new country, it would have to apply for membership and wait its turn along with Albania, Serbia, and other wannabe members. It seems very possible, though, that the eurocrats may be friendlier to the notion of Scotland keeping its membership this time around, if only to stick it to the English.

Fallout from Brexit will definitely raise the stakes for Scottish independence. For one thing, the pro-Brexit British government likely to take the place of the departing David Cameron, is likely to enact more restrictive immigration and asylum policies. An independent Scotland, on the other hand, will probably to go in the opposite direction and could even join the EU’s passport-free travel zone, the Schengen Area. If that happens, what’s to stop EU workers and non-European immigrants from using independent Scotland as a stepping stone to travel to the rest of Britain? The idea of physical border controls between Scotland and England, two countries that have been united since 1707, still seems pretty unfathomable, but we’re in a brave new world today.

The consequences for Northern Ireland, which voted 56 to 44 percent to remain and is the only part of the U.K. that has a land border with the EU, could be even more serious. EU integration has been critical to the peace that has mostly prevailed in the region since the 1990s, after years of sectarian violence. Thanks to the EU, Northern Ireland has been able to remain under British rule, while still enjoying free commerce and unencumbered travel to the Republic of Ireland. Also thanks to the EU, which state Northern Ireland is a part of simply didn’t matter quite as much. Additionally, Northern Ireland has received billions of pounds in funding from the EU, helping it attract growing tourist, IT, and—thanks to Game of Thrones—film production industries, after decades of economic stagnation.

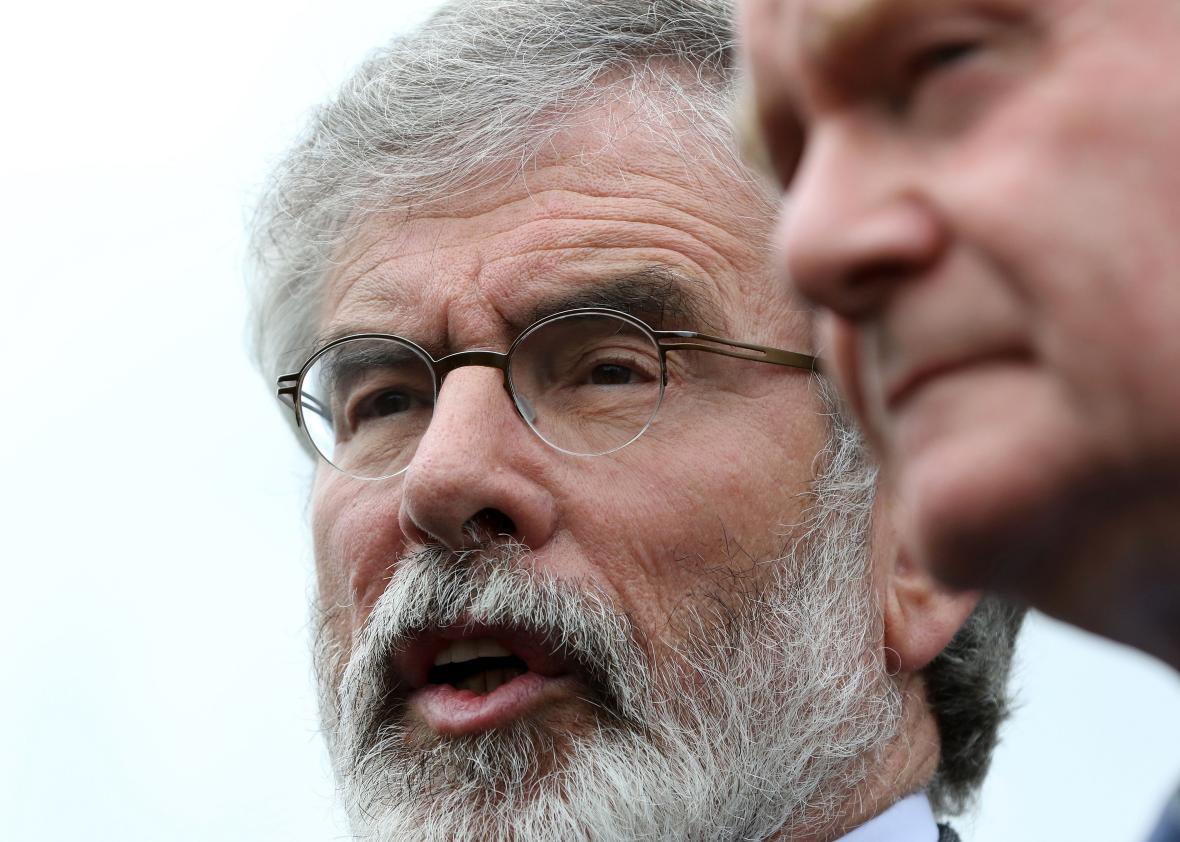

In the lead-up to the Brexit vote, Cameron had warned that withdrawal from the EU could lead to the reimposition of border controls between Northern Ireland and the republic. This morning, Northern Ireland’s Deputy First Minister Martin McGuiness, a member of the republican Sinn Fein party, called for a vote on pulling Northern Ireland out of the United Kingdom and uniting it with the Republic.

That seems unlikely to happen, but the vote has already added another fault line to Northern Ireland’s already polarized politics. If Protestants and Catholics go back to arguing about which country they should be a part of, rather than just how to share power, it doesn’t bode well for Northern Ireland’s hard-won and fragile peace and stability.