In parts of Latin America and the Caribbean, Zika is already an epidemic. Millions are infected, and there are rampant fears of microcephaly in infants, which in recent weeks has been more closely linked to the virus. But here in the United States, as my colleague Eric Holthaus reported in Slate last month, disease experts have assured us that fear of an impending Zika outbreak is overblown.

But according to a new study published in the journal PLOS Current Outbreaks, there is a very real risk of a Zika outbreak in many parts of the U.S. as early as this summer. The summer months mean increasing numbers of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes—the ones that carry Zika, as well as dengue and yellow fever viruses. For the study, researchers at the National Center for Atmospheric Research and the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center ran computer simulations incorporating weather and other variables to assess the outbreak risk for 50 cities.

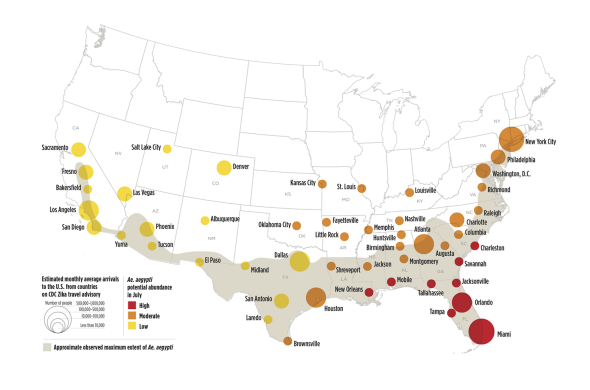

Here’s the map they came up with showing which areas are most likely to be affected. As you can see, the greatest risk appears in a band around the southeast of the country:

NCAR

The most vulnerable regions, researchers found, were southern Florida and south and southeast Texas. That isn’t surprising. Mosquito-borne viruses rely on mosquitoes, which rely on warm weather and standing water, and these are hot places. But even NYC could experience a “moderate abundance” of mosquitoes, according to the study. Your risk of infection decreases as you move west.

In addition to weather, the study examined travel patterns to determine where infection would be geographically likely (i.e. in regions where people might arrive after visiting a Zika-infected country) and what other factors could exacerbate it (poverty, the urban environment). Florida and Texas, which can play host to Aedes aegypti even in the winter months, are also closest to affected countries in Latin America.

Moreover, impoverished communities often face a greater risk of infection because, as a news release from NCAR notes, “lower-income residents can be more exposed to mosquito bites if they live in houses without air conditioning or have torn or missing screens that enable mosquitoes to enter their homes more easily.” The poverty along the U.S.-Mexico border, therefore, could contribute to increased risk.

So which is it, panic or not panic?

Not panic. First, research like this will enhance our efforts in surveillance and prevention of a potential outbreak, the researchers say. “Even if the virus is transmitted here in the continental U.S., a quick response can reduce its impact,” said Mary Hayden, a medical anthropologist and co-author of the study.

Second, Zika will spread less dramatically in the U.S. than it has in Latin America, according to the study, because of our sedentary, office-confined American lifestyles. We spend more time holed up in our air-conditioned cubicles, making us less likely to be exposed to mosquitoes. Finally, an upside!