State senators in Virginia approved a bill on Monday that would allow the state to execute death row inmates using the electric chair when lethal injection drugs are unavailable. The point of the bill is to provide a workaround for the nationwide shortage of lethal injection drugs, which European manufacturers have declined to make available for use in executions. The bill represents the latest instance of a state dealing with the drug shortage by turning to other forms of execution. Last year, Utah did so by reinstating the firing squad.

Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe, who will have the opportunity to veto the state’s electric chair bill, has not given any indication as to whether he approves of it or not. The bill comes about a year after the Virginia House of Delegates voted down a proposal to allow the state to keep secret the names of companies providing lethal injection drugs, in an effort to protect manufacturers from criticism and thereby make them less reluctant to provide the drugs.

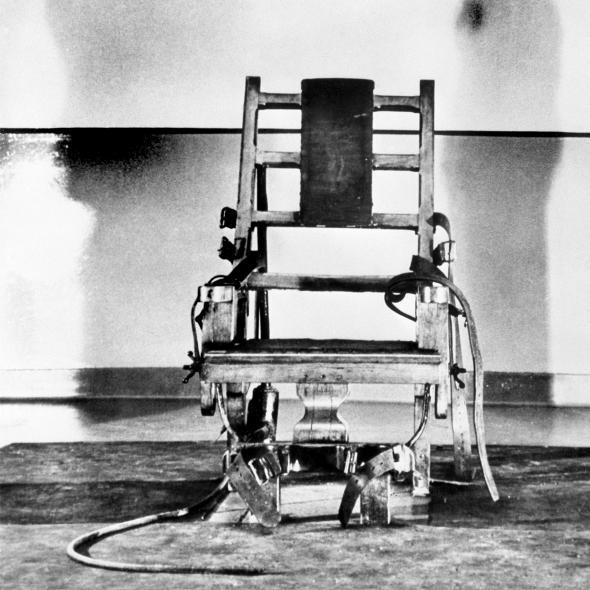

The electric chair has been in use in Virginia for decades. Since 1995, however, it has been presented to inmates as an option rather than a requirement; people facing execution could choose to die by lethal injection if they preferred it to the alternative. Only seven of the 87 people who have been put to death in the state since 1995 have chosen the electric chair over lethal injection. If the bill that’s currently under discussion passes, the Virginia Department of Corrections will be able to impose the electric chair on inmates if can’t meet the increasingly difficult challenge of securing the drugs needed for lethal injection.

A similar bill became law in Tennessee in 2014, prompting a lawsuit by a group of 10 death row inmates arguing that use of the electric chair violates the U.S. Constitution’s provision against cruel and unusual punishment. According to the plaintiffs, the electric chair essentially “cooks” the condemned person’s organs, and does not render them unconscious while the electrocution takes place. The lawsuit—which was stopped in its tracks by the Tennessee Supreme Court last summer on the basis that plaintiffs could only bring the challenge if they already knew for a fact they’d face the electric chair—included a gruesome description of an electrocution that took place in 2007, when Daryl Holton was put to death for murdering his three sons and stepdaughter:

A loud bang sounded, Holton’s body jerked violently upward and remained there. The black shroud fluttered and witnesses may have heard Holton sigh. Holton’s hands gripped the electric chair’s arms tightly and turned red. After approximately 20 seconds, Holton’s body slumped over. … Approximately 15 seconds later, a loud bang sounded, and Holton’s body jerked higher than it jerked the first time. Holton’s hands continued to grip the electric chair, and they turned bright red. After approximately 15 seconds, Holton’s body slumped.

In recent years, the death penalty in Virginia has been imposed less and less frequently. As University of Virginia School of Law professor Brandon Garrett reported for Slate last October, “Virginia has sentenced just 20 people to death in the past decade… a steep drop from the 1990s, when five to 10 people each year were sentenced to death.” Garrett’s explanation for the decline: Thanks to regional capital defense resource centers set up in 2004, the lawyers defending defendants in capital cases have become more specialized and effective.

That doesn’t help the seven prisoners currently on Virginia’s death row, who may soon be facing a situation in which the electric chair is the only method of execution available. And as jurisdictions that allow the death penalty—capital punishment is legal in 31 states—continue to grapple with shortages of the drugs used in executions, we can expect to see more bills like the one Virginia is considering.