Already battered by the double blow of the Greek financial crisis and a the political challenges posed by a massive influx of refugees, the EU’s trials are only just beginning. Britain is now threatening to leave the union entirely if its demands are not met, a process that Prime Minister David Cameron may have very little control over.

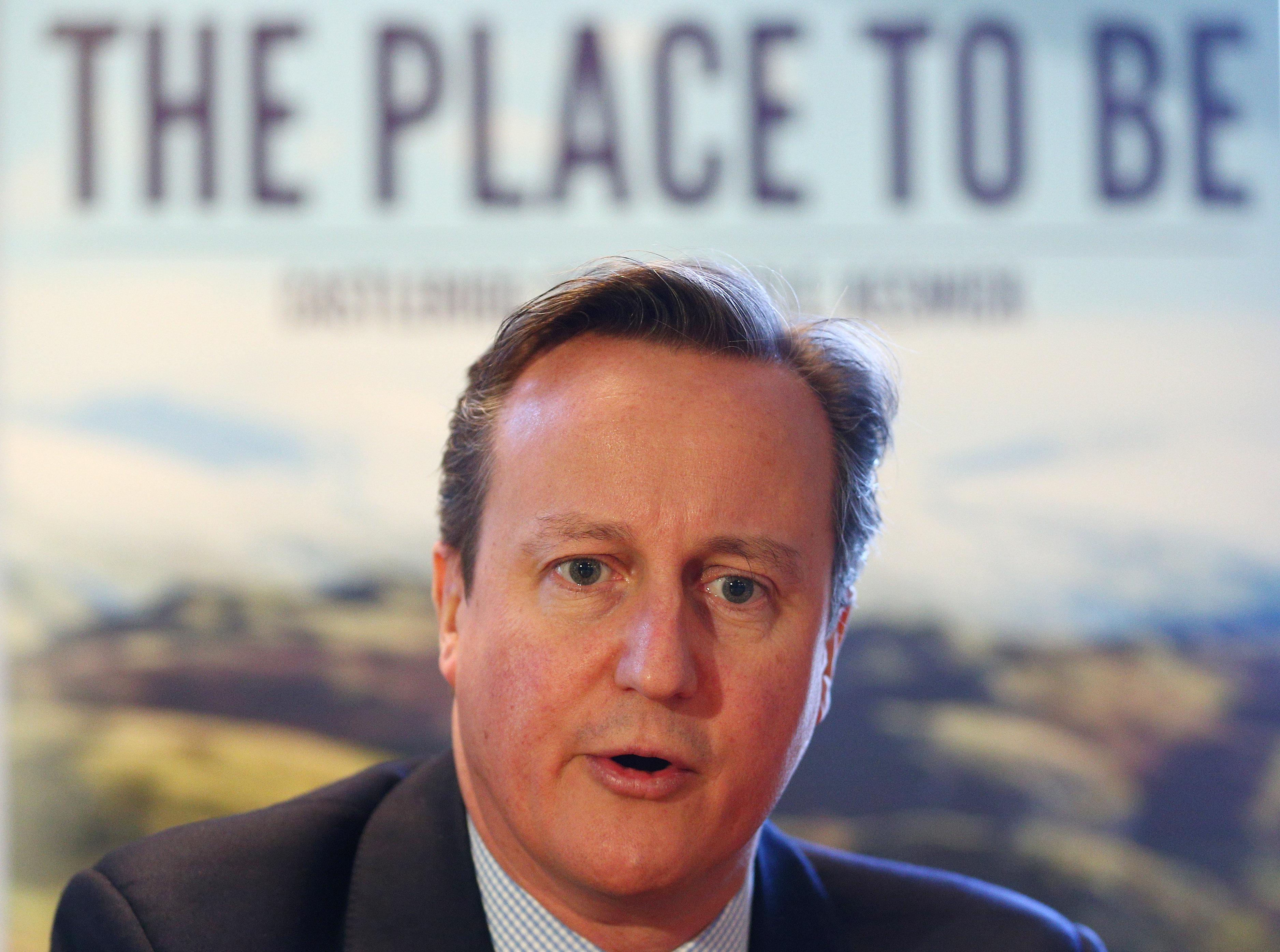

Cameron’s Conservative Party won last May’s general election, promising to hold a public referendum on EU membership. While many members of the party favor a “Brexit,” as they are calling it, Cameron favors staying in, but promised to renegotiate the terms of Britain’s membership, including controls on immigration as well as guarantees of the country’s continued political independence.

Tuesday, European Council President Donald Tusk put an offer on the table. “To my mind it goes really far in addressing all the concerns raised by Prime Minister Cameron. The line I did not cross, however, were the principles on which the European project is founded,” Tusk wrote in an open letter accompanying the proposal. The proposal does indeed respond to all of Cameron’s demands, but doesn’t actually meet them.

A chief concern of the Brits is welfare benefits for EU migrants. Cameron wants EU migrants to have to live in Britain for a minimum of four years before being able to receive tax credits or child benefits. Tusk’s proposal would allow the British to put a temporary “emergency break” on these benefits if there were an exceptionally large number of new migrants, though it’s not clear for how long. Cameron also wants to ban foreign workers from sending child benefits to children back in their home countries. Tusk didn’t agree to this, but his proposal would allow workers from lower-income countries to be paid less in benefits.

Cameron’s party also wants language specifying that the EU’s stated goal of an “ever closer union” does not apply to Britain. Tusk met him halfway, agreeing to affirm that Britain “is not committed to further political integration into the European Union.” Cameron wants national parliaments to have more power to block EU legislation. The EU offer would allow them to veto particular EU laws if more than half of the union’s parliaments are opposed. Actually putting that into practice would require Britain to forge alliances with other EU member states, something it was having some trouble doing even before this latest demand for special treatment.

Still, Cameron says he’s happy with the proposal. “Britain truly can have the best of both worlds. In the parts that work for us and out of the parts that don’t,” he told parliament this week. But he has two tough lobbying efforts ahead of him.

The proposal still has to be approved by the EU at a summit on Feb. 18. Cameron will spend the next few days traveling to European capitals on a charm offensive. He’s likely to encounter some skepticism, particularly in the Eastern European countries where many of Britain’s migrants come from.

If the deal is approved by the EU, Cameron is expected to call for a referendum back home in June. Cameron can likely count on the support of the opposition Labour party, but the conservative members of his own party will be a tougher sell. “The thin gruel has been further watered down,” one Tory MP said of Tusk’s response to Cameron’s demands. Nigel Farage, leader of the insurgent, anti–EU UK Independence Party, was probably not going to be convinced by any proposal Cameron brought to the table, but for good measure called the deal “truly pathetic.”

Recent polls show 43 percent of Brits in favor of leaving the EU, 36 percent wanting to stay, and 21 percent undecided. And the number of pro-Brexit voters has been increasing. An exit could have serious consequences for Britain as well as the rest of the EU, ranging from financial markets to scientific research. And with serious challenges including terrorism and migration in need of unified solutions, it would deliver a brutal blow to the union’s political credibility at a time when it doesn’t have a lot to spare.