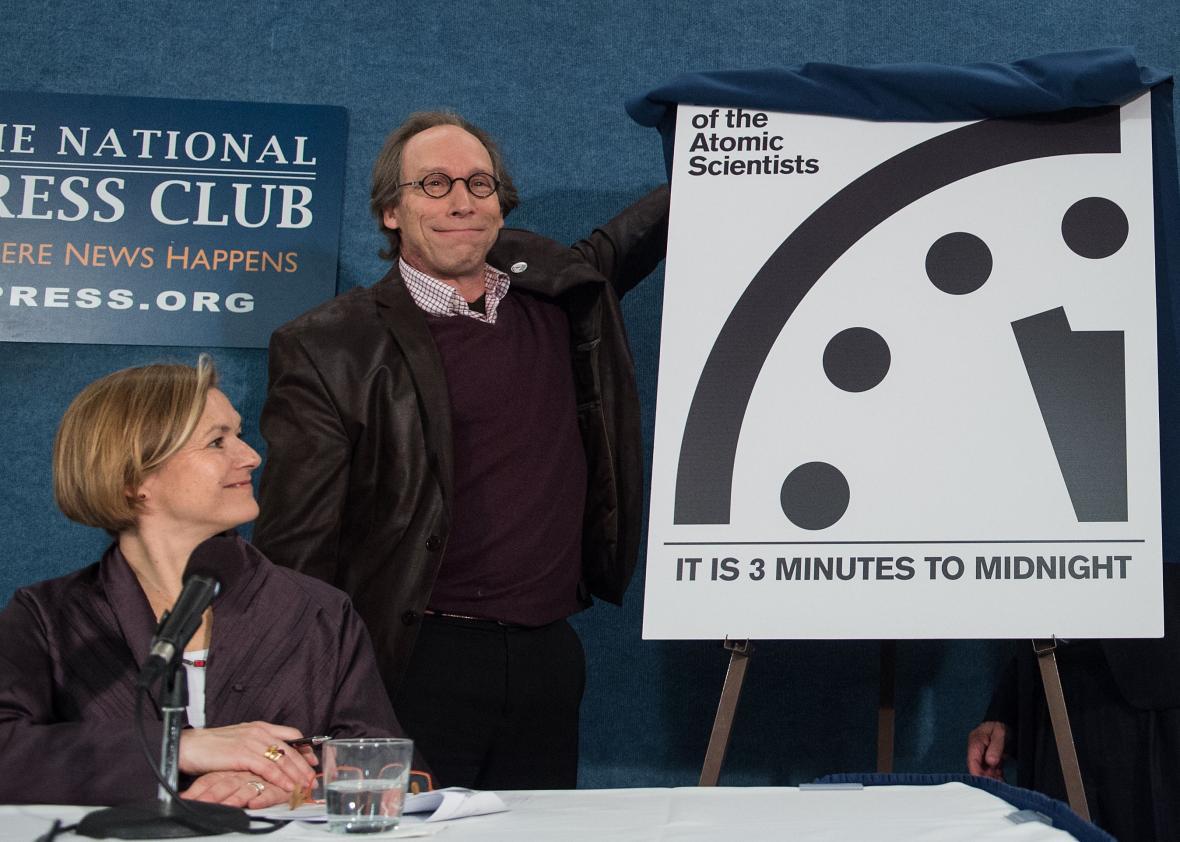

Despite a major nuclear deal with Iran and a landmark global agreement on reducing greenhouse emissions, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ famous “Doomsday Clock,” which had its annual unveiling Tuesday, remains unchanged at three minutes to midnight.

Introduced in 1947, the clock serves as “a metaphor for how close we are to destroying the planet,” as Bulletin’s publisher Rachel Bronson put it Tuesday. The closer the clock is set to midnight, the higher the risk. While initially focused on the risk of catastrophic nuclear war, the Bulletin has expanded its remit in the past decade to include things like climate change and chemical weapons. The clock reached its closest to midnight at two minutes in 1953 following the first U.S. hydrogen bomb test. It reached a record 17 minutes to midnight in 1991 following the end of the Cold War. Last year, as my colleague Will Oremus wrote, it was set to three minutes, the closest to the world ending since 1984, due in large part to global failures to address the threat of climate change.

But while the impact of climate change was certainly undeniable during the hottest year on record, shouldn’t December’s climate agreement have moved the needle at least a little bit? At Tuesday’s clock unveiling ceremony in Washington, Sivan Kartha, a climate change expert on the Bulletin’s science and security board said, “We have to call Paris only a tentative success. The emission reduction pledges are manifestly, unequivocally inadequate” and “need to be matched with actions.”

As for nuclear risks, former U.N. Ambassador Thomas Pickering called the Iran nuclear deal merely “a relatively bright spot in a difficult horizon.” In addition to concerns about the implementation of that deal, the experts pointed to other global nuclear risks, including escalating tensions between nuclear superpowers Russia and the United States, which make further disarmament unlikely. India and Pakistan continue to expand their arsenals and global efforts to curb North Korea’s nuclear ambitions have failed dismally.

While the Bulletin moved the clock back a minute following the election of Barack Obama, and his pledge to seek a world free of nuclear weapons, the experts have been disappointed by his record since then, in particular the massive ongoing U.S. nuclear modernization program. “What message does this send to non-nuclear weapons about our intentions?” asked the board’s chairman, physicist, and Slate contributor Lawrence Krauss.

While all these threats and concerns are quite real, this seems a bit too dour. If we limit the discussion to nukes, it’s hard to argue that the world is at greater risk now than it was at the height of the Cold War. And as I’ve written before, I think the decision to expand the clock to non-nuclear threats dilutes the clock’s metaphorical power. It’s not that climate change isn’t a major threat, but unlike with nuclear war, we’re now no longer talking about the risk of a specific event. The world isn’t going to “prevent” climate change. It’s already happening and it’s going to get worse. The question is how much can we limit and prepare for its effects.

In 1963, the clock was set back from seven minutes to 12 minutes after the signing of the U.S.-Soviet partial test ban treaty. As the Bulletin’s website puts it, then the treaty represented “progress in at least slowing the arms race” and “awareness among the Soviets and United States that they need to work together to prevent nuclear annihilation.” Similarly, the Iran deal and the Paris agreement didn’t eliminate the risks of nuclear war or climate change, but represented tangible progress and an acknowledgment of risks. If the purpose is to urge leaders to address problems, that ought to be worth a minute or two.