On Wednesday, the Supreme Court handed down a major death penalty decision that is sure to frustrate abolitionists who are still delighted over last week’s smackdown of Florida’s death penalty scheme. The opinion, penned by Justice Antonin Scalia, reversed a Kansas Supreme Court ruling that had mandated stringent procedural safeguards for capital defendants. In addition to clearing the way for three executions in the state, the court’s judgment calls into question optimistic speculation that the end of the death penalty is nigh.

Kansas v. Carr, as the case is called, involved two procedural protections crafted by the Kansas Supreme Court. The first protection revolved around “mitigating factors,” which a capital defendant may put forward to persuade a jury not to sentence him to death. Under the Eighth Amendment, capital defendants hold a right to present such mitigating factors to the jury. In Kansas, these factors need only have been presented to juries, not proved beyond a reasonable doubt, like the actual guilt of a defendant. The Kansas Supreme Court found that trial judges must inform juries of this fact, lest jurors fault defendants for not proving mitigating factors beyond a reasonable doubt, as they expected prosecutors to do to demonstrate guilt. But Scalia reversed that decision, holding that mitigation is “largely a judgment call (or perhaps a value call)” involving “a question of mercy”’—not a factual finding. Because mitigation is so abstract and value-laden, Scalia wrote, courts need not assign any particular standard of proof to mitigating factors.

The second question in Carr was equally tricky: whether capital defendants must be sentenced separately, at different hearings. Jonathan and Reginald Carr were sentenced together. But the court’s Eighth Amendment cases have insisted that capital defendants must be given “individualized sentencing” in order for the jury to find “an individualized determination” that the death penalty is appropriate. But the court has never insisted that capital defendants must be sentenced by themselves, at their own hearing, without any co-defendants present. The Kansas Supreme Court took that next step, finding that the Carr brothers’ joint sentencing prevented the jury from individually assessing their culpability. (In particular, the court fretted that the brothers were unable to blame each other for their crimes, a common defense among murderous duos, since they were sentenced jointly.) But Scalia disagreed, holding that “only the most extravagant speculation” would lead to the conclusion that the joint sentencing had undermined the brothers’ defense.

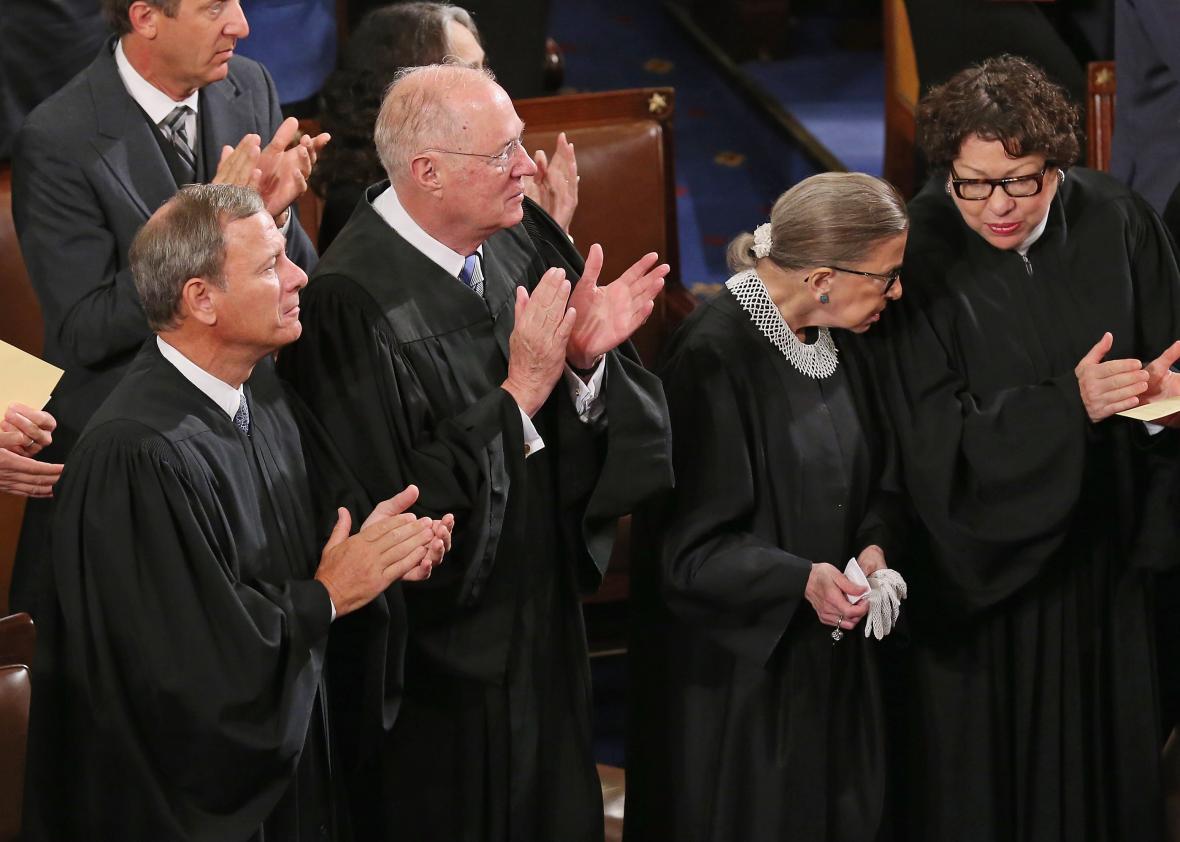

Surprisingly, the court’s decision was 8–1, with only Justice Sonia Sotomayor dissenting. Justices Stephen Breyer and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who believe the death penalty is unconstitutional, joined Scalia’s opinion, suggesting that they will continue to support capital punishment in certain circumstances until the court strikes it down altogether.

In her lone dissent, Sotomayor argued that the court should have simply dismissed the case, rather than reaching the merits. Kansas, Sotomayor wrote, may have “overprotected” its citizens’ federal rights by crafting new rules about mitigating factors and joint sentencing. Still, the court should not pass judgment on this “state experimentation,” because “in so doing, the court risks discouraging states from adopting valuable procedural protections even as a matter of their own state law.” Sotomayor is irritated that, in ruling that the Eighth Amendment doesn’t require these safeguards, the court dismissed their usefulness altogether—a move that may dissuade other states from adopting them.

To my mind, Sotomayor is right that Scalia’s opinion unnecessarily derides Kansas’ capital sentencing safeguards. But I’m disappointed that she didn’t go a step further and, at the very least, affirm the constitutional necessity of a clear jury instruction regarding mitigating factors. There is a real possibility that jurors could mistakenly believe that mitigating factors must be proved beyond a reasonable doubt; after all, they hear this standard repeated endlessly throughout the trial. Requiring judges to simply remind jurors that mitigating factors need not be proved would cost the prosecution nothing, would and lend clarity and validity to the jury’s final sentence. America’s death penalty system is probably too cruel, corrupt, and racist to salvage. But the court might have used Carr to inject a little more fairness into proceedings that are fundamentally unjust.