At fertilization, you are dealt a genetic hand of cards. Your genome largely dictates whether you will be short or tall, able to taste certain chemicals, or prone to some types of cancer. But what if it were possible to stack the deck?

That was the question facing the International Summit on Human Gene Editing, a public meeting convened with an organizing committee of 10 scientists and 2 bioethicists to address the ethical and biomedical ramifications of powerful new genetic technologies. The three-day forum, which concluded Thursday in Washington D.C., ended by proposing a path forward for researchers when it comes to using these technologies. The committee’s takeaway: Future research into gene editing—especially when it involves human cells that would be passed down to future generations—must exercise extreme caution.

New genetic modification techniques have the potential to “eradicate genetic diseases and, ultimately, to alter the course of evolution,” as Jennifer Doudna of the University of California, Berkeley, wrote in an editorial in the journal Nature. Doudna, a pioneering geneticist, initially proposed the summit and served as a member of its 12-person committee.

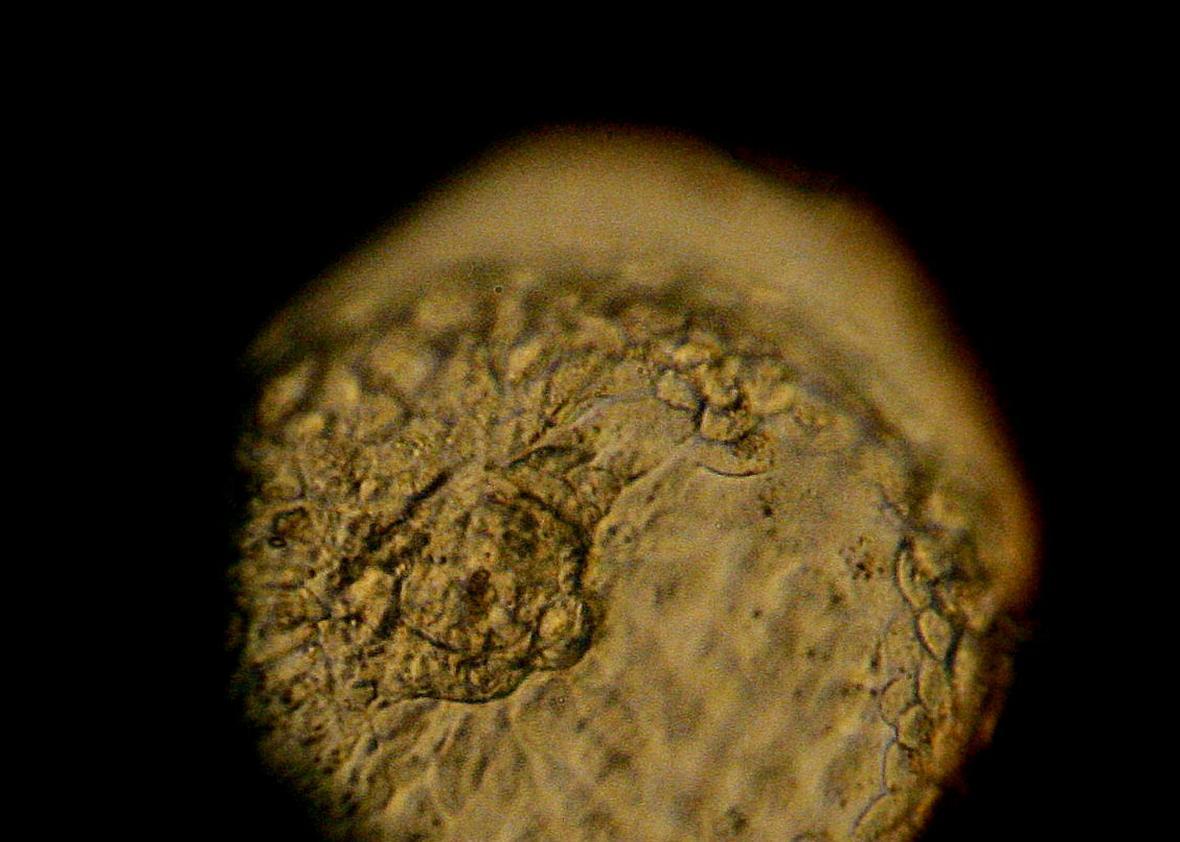

The most promising of these technologies, known as CRISPR, can be used to easily and cheaply make changes in the genetic material of a cell—including sperm, eggs, or embryonic stem cells. If these modified cells were used to create embryos that were allowed to develop, the genetic alterations would persist in any baby created from the modified cells. Those alterations would then be passed on to the next generation, and the next, and the next.

Gene editing has the potential to address serious genetic diseases. It could also be used to enhance human abilities—for instance, to implant in embryos a “short sleep” gene that would let someone function on just four or six hours per night, or even make glow-in-the-dark children, as science writer Sharon Begley points out in an excellent article summing up the forum.

These possibilities open up a Pandora’s box. The arguments on either side of gene editing are passionate. At the forum, many of those who had grappled with genetic disease, as well as the scientists who treated them, said there was a moral duty to continue with research that could eradicate disease and human suffering. Others called for a two-year worldwide moratorium on such research, such as Hille Haker, chair of Catholic Moral Theology at Loyola University, Begley reported.

CRISPR is easy to use and widely accessible. It’s also powerful and poorly understood. Using it without proper investigation could potentially introduce mutations—with unforeseen consequences—permanently into the human race. The implications go beyond any one individual: Like the planet, “the human genome is shared among all nations,” reads the committee’s statement. Yet, as Doudna writes, because it’s so easy to use and already so accessible and widespread, “a complete ban is impractical.”

With this in mind, the committee urged the international community to establish norms across countries, shared regulations, and an ongoing forum “to discourage unacceptable activities while advancing human health and welfare.” Perhaps the most strongly worded part of the statement warned against meddling with the human gene pool before far more research and ethical consideration had been taken into account. The committee wrote:

It would be irresponsible to proceed with any clinical use of germline editing unless and until (i) the relevant safety and efficacy issues have been resolved, based on appropriate understanding and balancing of risks, potential benefits, and alternatives, and (ii) there is broad societal consensus about the appropriateness of the proposed application.