A day after the attacks in Paris underlined the global danger posed by the continuing violence in Syria, Russia, the United States, and governments in Europe and the Middle East agreed at talks in Vienna to a road map for ending the devastating and destabilizing war.

The proposal, which appears to draw heavily from a Russian peace plan circulated before the talks, sets Jan. 1 as a deadline for the start of negotiations between Bashar al-Assad’s government and opposition groups. Within six months, they would be required to create an “inclusive and non-sectarian” transitional government that would set a schedule for holding new, internationally supervised elections within 18 months. Western diplomats involved in the talks told the Wall Street Journal that the meeting had produced more progress than expected, and the events in Paris may have added new urgency to the proceedings, given the need to build a united front against ISIS, but stumbling blocks remain.

The biggest one is the fate of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, whose role is side-stepped in the agreement. Russia and Iran, the latter of which is participating in international talks for the first time, say he’s a necessary bulwark against extremist groups like ISIS and al-Qaida. The U.S., Europe, and Sunni Middle Eastern powers pin blame for the conflict, including the rise of ISIS, on Assad, and say he must step down. The issue can’t be avoided forever: Saudi Arabia made clear Saturday that it would continue to support Syrian rebel groups if Assad does not step down. Secretary of State John Kerry suggested Saturday that Syrians could decide Assad’s fate through the democratic process, saying, “We did not come here to impose our collective will on the Syrian people.” This would seem to suggest that Washington is now open to him playing a role in the transition.

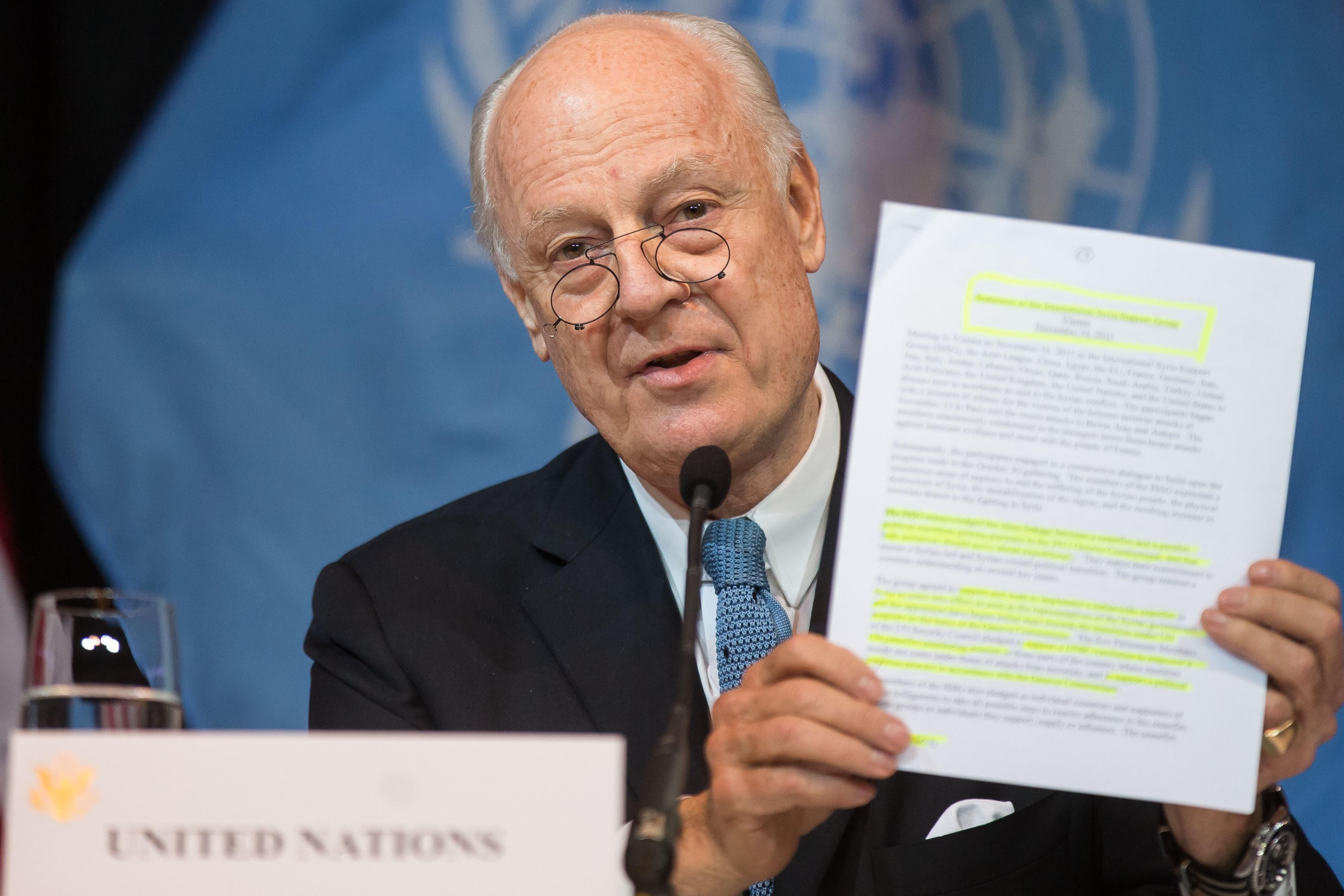

The other big stumbling block is which opposition groups are considered “legitimate.” The road map tasks U.N. envoy Staffan de Mistura with determining who should negotiate on behalf of the opposition with Assad, an idea that’s unlikely to go down well with many of the rebel groups that have been fighting the government for years. De Mistura may have his work cut out for him finding groups that are both willing to sit down with Assad under these circumstances and have enough credibility to make the process legitimate.

Any cease-fire between Assad, the rebels, and their respective international backers, would not apply to ISIS and the al-Qaida–linked Jabhat al-Nusra, but beyond that it gets a little murky. Russia is skeptical of the view that the non-Jihadist opposition to Assad exists at all. Saudi Arabia and Turkey, meanwhile, want the list of legitimate groups expanded to include several Islamist factions. The agreement tasks the Jordanian government with identifying which opposition groups should be considered terrorists.

The biggest reason for caution about the agreement is that no actual Syrians, from either side of the conflict, were party to it. The Syrian National Coalition, a Western-backed exile group, has already expressed skepticism about the 18-month timeline saying two to three years is more realistic—a dispiriting thought for a conflict already in its fifth year.

Syria will also be on the agenda at the G-20 meeting starting Sunday in Antalya, Turkey. President Obama will hold a bilateral meeting with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, a major backer of the rebels, as will Russian President Vladimir Putin. Obama and Putin have no formal meeting scheduled but are likely to discuss the conflict on the sidelines of the conference. In the wake of the attack, French President Francois Hollande has canceled his trip to the meeting.