The recent attention to police-involved killings has highlighted a truly astounding fact: No one really knows how often they happen. Individual police departments aren’t required to report to any centralized agency about how many people their officers have killed every year, and the one federal database on this subject that does exist is almost comically incomplete and unreliable.

That database, maintained by the FBI, suffers from at least three flaws: It only tracks killings that police departments have deemed “justifiable,” it relies on police departments to submit incident reports on a purely voluntary basis, and it doesn’t collect any detailed information on the circumstances surrounding each incident.

In an article published Thursday based on a cache of raw FBI data covering the 10-year period between 2004 and 2014, the Guardian confirmed that the federal government’s system for tracking police killings is profoundly inadequate. According to the article, only 224 out of the nation’s 18,000 police departments reported any incidents involving their officers killing people during the year 2014. Those departments reported a total of 439 justifiable homicides for the year. But that number is almost certainly very low given that the the Guardian’s own, independent count of police killings has already tracked 900 incidents—justifiable and otherwise—over the past nine and a half months. “We have no way of knowing how many incidents may have been omitted,” FBI spokesman Stephen Fischer told the Guardian in an email.

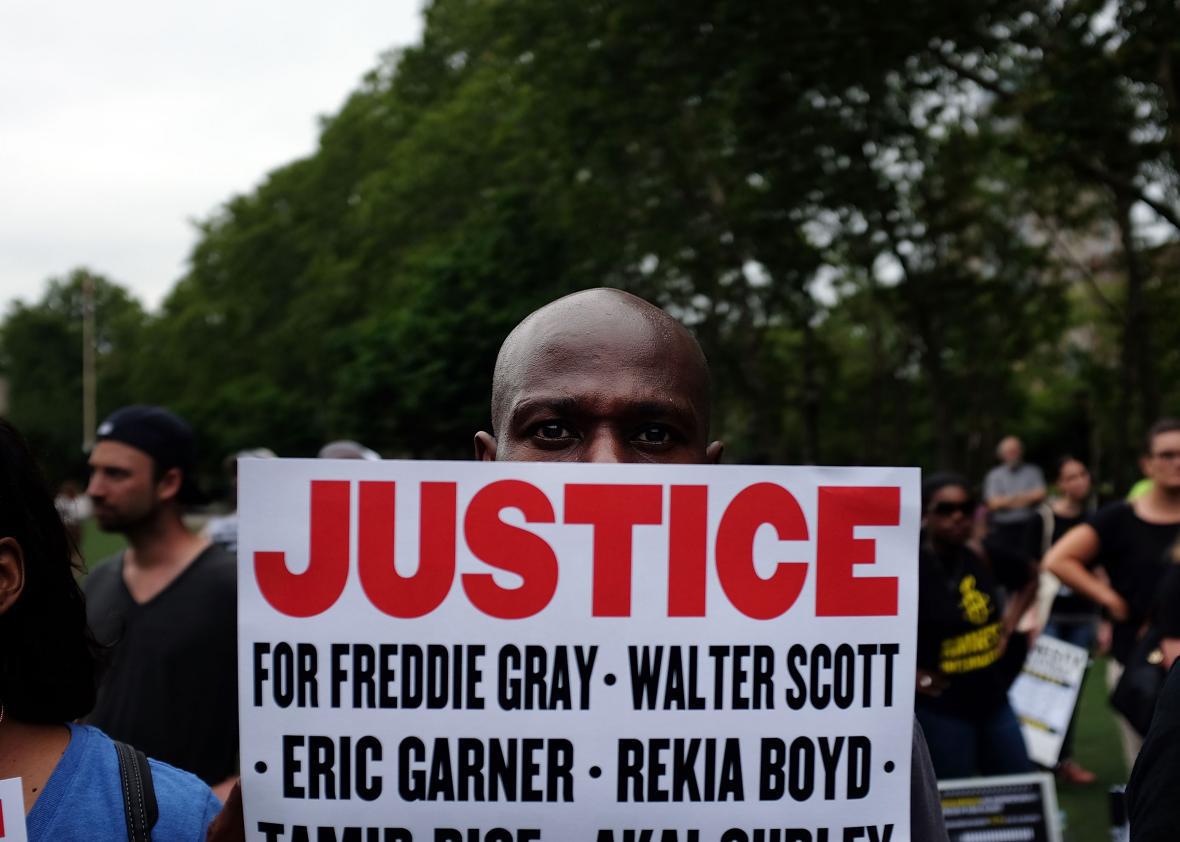

It’s important to note that many of the departments probably didn’t report any data to the FBI during the past decade because their officers didn’t kill anyone. Still, the Guardian illustrates how much is being left out of the FBI count by pointing out that three of the most high-profile incidents involving black men who died at the hands of police in recent years—Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, and Oscar Grant—could not be found in the data set obtained by reporters.

The need for better record-keeping on police-involved killings has been acknowledged recently by government officials at the highest level. At a private meeting of lawmakers on Oct. 7, FBI director James Comey said it was “embarrassing and ridiculous” that members of the public cannot get information from the FBI on violent encounters between police and civilians. Earlier that week, Attorney General Loretta Lynch announced that the Bureau of Justice Statistics, a division of the Justice Department, had begun a pilot program—modeled after information-gathering efforts by the Guardian and the Washington Post—aimed at collecting data on police-involved killings.

Lynch told reporters, “the department’s position and the administration’s position has consistently been that we need to have national, consistent data both on excessive force and on officer involved shootings.”

I emailed Stephen Fischer, the FBI spokesman, to ask what factors are considered when a police department makes the decision on whether to submit data to the FBI or not. Fischer declined to comment on the subject. “It is up to the individual department to decide whether to report or not,” he wrote in an email. “I can’t speak for individual departments. … It could be one of a variety of reasons.”

That’s another problem with the current opt-in model of data collection: Even the FBI doesn’t know why a particular department is or isn’t reporting police-involved killings.