CNN redeemed itself Tuesday night. The network botched last month’s GOP debate by entrusting it to Jake Tapper, a likable and talented journalist who wasn’t ready to moderate a debate. Tapper was either unable or unwilling to direct conversational traffic among the 11 Republican candidates onstage, and the result was a chaotic and unsatisfying three-hour slog that revealed little except the deficiencies of the format; the moderator; and, perhaps, the network that employs him.

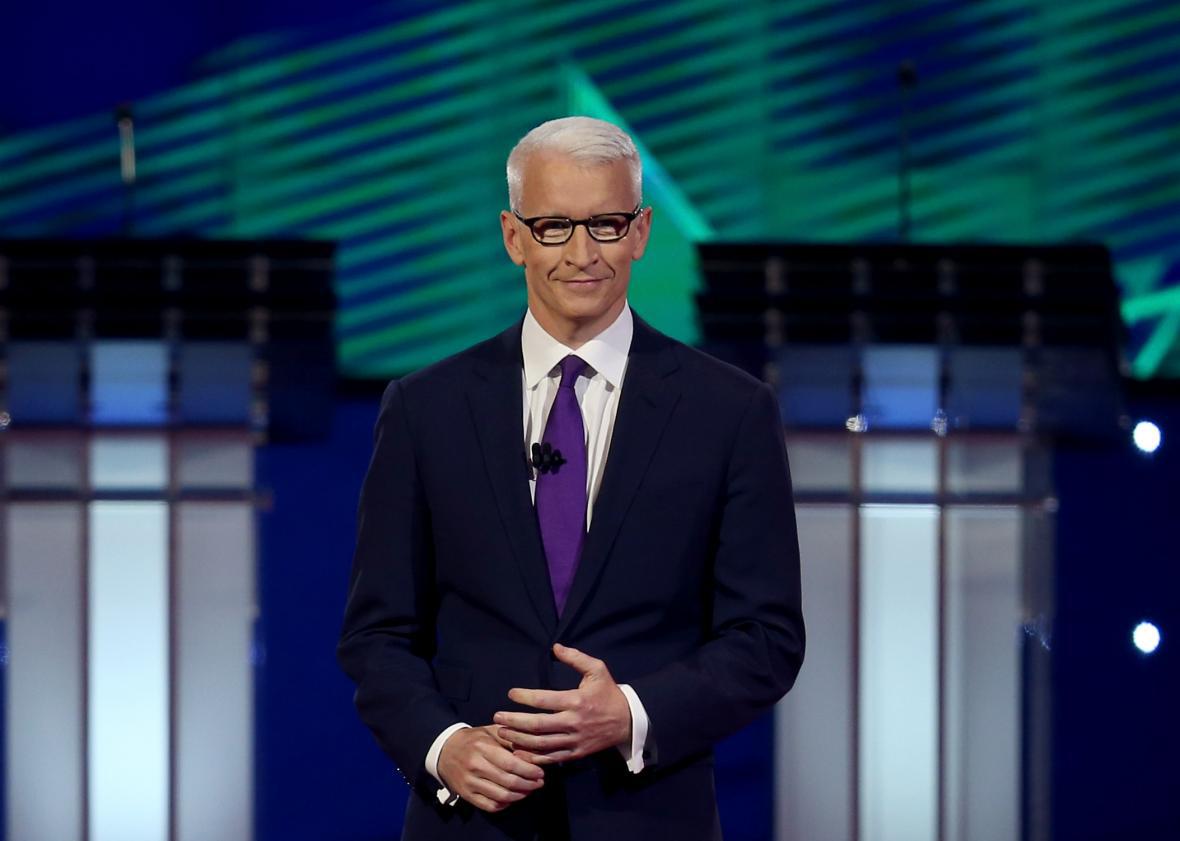

Tuesday night’s Democratic debate was the polar opposite of its predecessor: brisk, informative, issue-focused, and constructively adversarial. Credit for that goes to moderator Anderson Cooper, who showed Tapper and the nation how a lively debate is supposed to proceed and how critical the moderator is to its success.

With Dana Bash, Don Lemon, and Juan Carlos Lopez providing support—Twitter critics have suggested the network marginalized Lemon and Lopez by only assigning them questions pertaining to their ethnicities—Cooper asked good questions and made sure they were answered. During Tapper’s GOP debate last month, I was so annoyed by his “fight-among-yourselves” moderating strategy that I published a post rephrasing his bad questions as good ones. I expected to write a similar post Tuesday night—but I never got the chance.

I had reason to be skeptical that Cooper could run a good debate. The CNN anchor is a full-fledged celebrity, someone who travels in the same social stratum as the candidates and their financial backers, and I worried he would let them off easy as a result—that he’d be unwilling to risk looking like a bully by being firm. But I think Cooper’s celebrity status actually empowered him to be tough. America already likes him, and he knows that.

By keeping the debate brisk and well-directed rather than allowing the candidates to slow the pace with constant interruptions and rebuttals, and by mixing questions designed to elicit long answers with ones meant to be answered in a sentence or two, Cooper kept the candidates off-balance and forced them to engage with one another and with the topics at hand. When the candidates discussed policies and laws that might have been unfamiliar to the audience, Cooper broke in to provide background.

Cooper began with questions about each candidate’s electability—a valid line of inquiry for a primary debate. (Debates become tedious when electability considerations are the only topic.) He came out strong, with pointed questions requiring the candidates to address their weaknesses. Take the question he directed to former Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley: “Gov. O’Malley, the concern is that you tout your record as Baltimore’s mayor. That city exploded in riots and violence in April. The current top prosecutor in Baltimore, also a Democrat, blames your zero-tolerance policies for sowing the seeds of unrest. Why should they elect you?”

When O’Malley defended his record in Baltimore, Cooper was ready with a follow-up: “In one year alone, though, 100,000 arrests were made in your city, a city of 640,000 people. The ACLU [and] the NAACP actually sued you.” The most important thing a debate moderator can do is pay close attention and ask follow-up questions. Cooper did an excellent job of this.

He also didn’t let them off the hook. At one point he asked Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, “As a congressman, you voted against the Iraq War. You voted against the Gulf War. You’re just talking about Syria. But under what circumstances would a President Sanders actually use force?” Sanders sidestepped the question to respond to something Hillary Clinton had said moments earlier. Cooper allowed him to say his piece but didn’t let him dodge the question. “Sen. Sanders, you didn’t answer the question,” Cooper said. “Under what circumstances would you actually use force?”

If Cooper was firm with Sanders and O’Malley, he was a bit indulgent with Clinton, the presumptive nominee. When she exceeded her time, he’d interject a polite and quiet “Thank you” and then allow Clinton to continue until she had finished her point. That was the only major flaw I noticed in Cooper’s performance, and I think it’s excusable. The former secretary of state is the front-runner among the Democrats, and as such it’s OK to give her a bit more time to answer. Similarly, I wasn’t bothered that fringe candidates like Jim Webb and Lincoln Chafee disappeared for long stretches of time. Webb complained repeatedly about not being given enough time to make his points, but I think Cooper was right to apportion speaking time roughly based on each candidate’s level of support.

No matter who was speaking, Cooper was always constructively adversarial: unafraid to push back on an unsatisfying answer and unwilling to let candidates get away with cant and sloganeering. “In all candor, you and your husband are part of the 1 percent. How can you credibly represent the middle class?” he asked Clinton at one point. Later, Clinton replied to a question about how her presidency would differ from Barack Obama’s by citing her gender, to great applause. Cooper wouldn’t let her get away with that. “Is there a policy difference?” he asked.

And Clinton actually answered the question, or tried to. That’s what moderators are supposed to do: get the candidates off their talking points and force them to engage. Cooper succeeded, and the difference between his work and his predecessors was obvious not just to viewers but to the candidates themselves. “What you heard tonight, Anderson, and all of you watching at home, was a very, very different debate from the sort of debate that you heard from the two presidential Republican debates,” said O’Malley at the end of the night. Much of the credit for that goes to Anderson Cooper. I wish he could moderate all the upcoming debates.