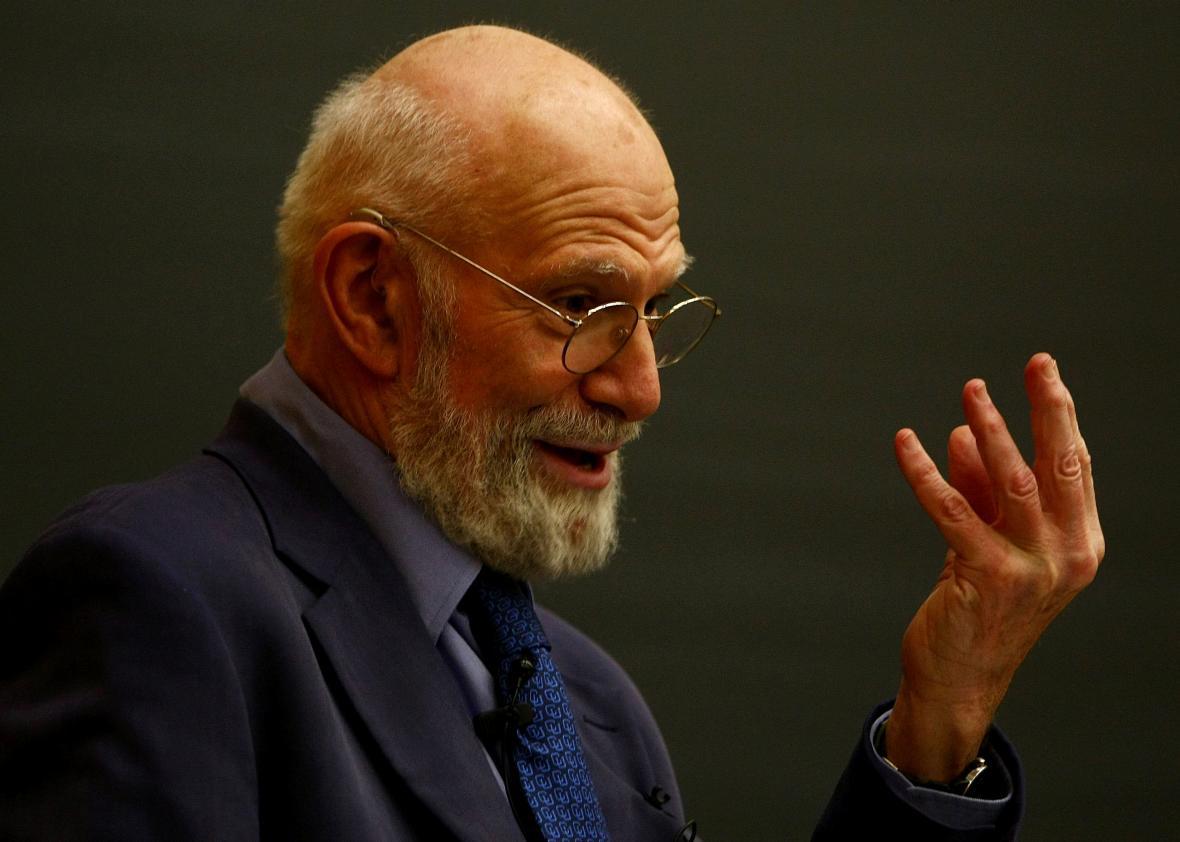

Oliver Sacks, the eminent neurologist and bestselling author, died at his home in New York on Sunday. He was 82. The doctor who used unusual mental disorders to talk about larger themes of the human condition died of cancer, his longtime personal assistant told the New York Times. As a writer with more than one million copies of his book in print in the United States alone, Sacks had a level of popularity that was almost unparalleled in the scientific world and reportedly received about 10,000 letters a year.

His death hardly comes as a surprise. In February, Sacks wrote an op-ed piece for the Times in which he announced that he had a rare type of cancer that had metastasized in his liver and he had months to live.

“Over the last few days, I have been able to see my life as from a great altitude, as a sort of landscape, and with a deepening sense of the connection of all its parts,” Sacks wrote. “This does not mean I am finished with life. On the contrary, I feel intensely alive, and I want and hope in the time that remains to deepen my friendships, to say farewell to those I love, to write more, to travel if I have the strength, to achieve new levels of understanding and insight.”

A professor of neurology at New York University School of Medicine, Sacks wrote more than a dozen books, most of which were about unusual medical conditions, including The Man Who Mistook his Wife for a Hat and The Island of the Colourblind. One of the London-born academic’s first books, Awakenings, about how he used an experimental drug to awaken patients who had been in a coma-like state for years was turned into a movie starring Robert De Niro and Robin Williams and was nominated for three Academy Awards, including best picture. In a video posted on his YouTube channel, Saks explained that “the act of writing, when it goes well, gives me a pleasure, a joy, unlike any other.”

As a prolific writer who was able to make science accessible to masses of readers, Sacks was adept at using the range of human experience to try to explain how the brain worked. The New York Times’ Michiko Kakutani writes of Sacks:

[He] was a polymath and an ardent humanist, and whether he was writing about his patients, or his love of chemistry or the power of music, he leapfrogged among disciplines, shedding light on the strange and wonderful interconnectedness of life — the connections between science and art, physiology and psychology, the beauty and economy of the natural world and the magic of the human imagination.

Although some have accused Sacks of exploiting his own patients for profit, he wrote about his subjects with a “capacious 19th-century humanity,” wrote Lisa Appignanesi in the Guardian earlier this year. In reviewing what would turn out to be his last book, the autobiography On the Move, Appignanesi writes:

His heroes are not Balzac’s provincials on the make in the glittering capital of corruption, but autistic boys with a genius for drawing or prime numbers; or a man afflicted by the tics and uncontrollable swearing of Tourette syndrome; or Dr P, a distinguished musician who has lost the ability to recognise faces but sees them where they are not.

For all their lacks and losses, or what the medics call “deficits”, Sacks’s subjects have a capacious 19th-century humanity. No mere objects of hasty clinical notes, or articles in professional journals, his “patients” are transformed by his interest, sympathetic gaze and ability to convey optimism in tragedy into grand characters who can transcend their conditions. They emerge as the very types of our neuroscientific age.

Instead of simply seeing his patients or cases as victims, Sacks often chose to focus “on how a neural abnormality can create surprising ability,” notes Bloomberg. A man with Tourette syndrome was a great jazz drummer, a woman with autism was able to design humane slaughterhouses and a painter who lost his ability to see color suddenly found new creative powers when he was only able to see in black and white, to name a few examples. Other times, supposed cures made things worse. The Associated Press points out how Sacks famously wrote about a blind man who became “very disabled and miserable” when he suddenly regained sight. Later in life, Sacks began to study hallucinations, in part inspired by his experimentation with LSD when he was young.

In a moving New York Times essay published in August about his relationship with his family’s Orthodox upbringing, Sacks wrote about how his parents reacted when he admitted he liked men. “You are an abomination. I wish you had never been born,” her mother told an 18-year-old Sacks. “The matter was never mentioned again, but her harsh words made me hate religion’s capacity for bigotry and cruelty.” The ending of the essay was the most poignant though, giving the reader an insight into how the writer and scientist was coming to peace with his own demise:

And now, weak, short of breath, my once-firm muscles melted away by cancer, I find my thoughts, increasingly, not on the supernatural or spiritual, but on what is meant by living a good and worthwhile life — achieving a sense of peace within oneself. I find my thoughts drifting to the Sabbath, the day of rest, the seventh day of the week, and perhaps the seventh day of one’s life as well, when one can feel that one’s work is done, and one may, in good conscience, rest.