Sierra Leone has gone a full week without a new case of the Ebola virus for the first time since the outbreak reached the country early last year, the World Health Organization reported this week. Last week the government lifted the largest remaining community-wide quarantine, allowing friends and relatives to reunite for the first time in months.

Nearly 4,000 people have died from Ebola in Sierra Leone, but the last death was two weeks ago. A few dozen people who had contact with victims will remain in quarantine until the end of this month, after which the country must go 42 days without a new case before it can be declared officially Ebola-free, but health workers believe the end is in sight.

Liberia, the country worst affected by the virus, hasn’t had a new case since six infections in mid-July sparked fears of a resurgence. In total, only three new cases of the disease were reported last week, all in Guinea. This is fairly remarkable given that almost 28,000 people have been infected with the disease and more than 11,000 have died since the outbreak began in December 2013. The outbreak caused untold damage to the economies and societies of the three countries where it was concentrated, as well as inciting public panic in many other places, including the United States, where it briefly spread. But it could have been worse: At one point the WHO forecasted that 1.4 million people could be infected, and some experts suggested it could become endemic in West Africa for years to come.

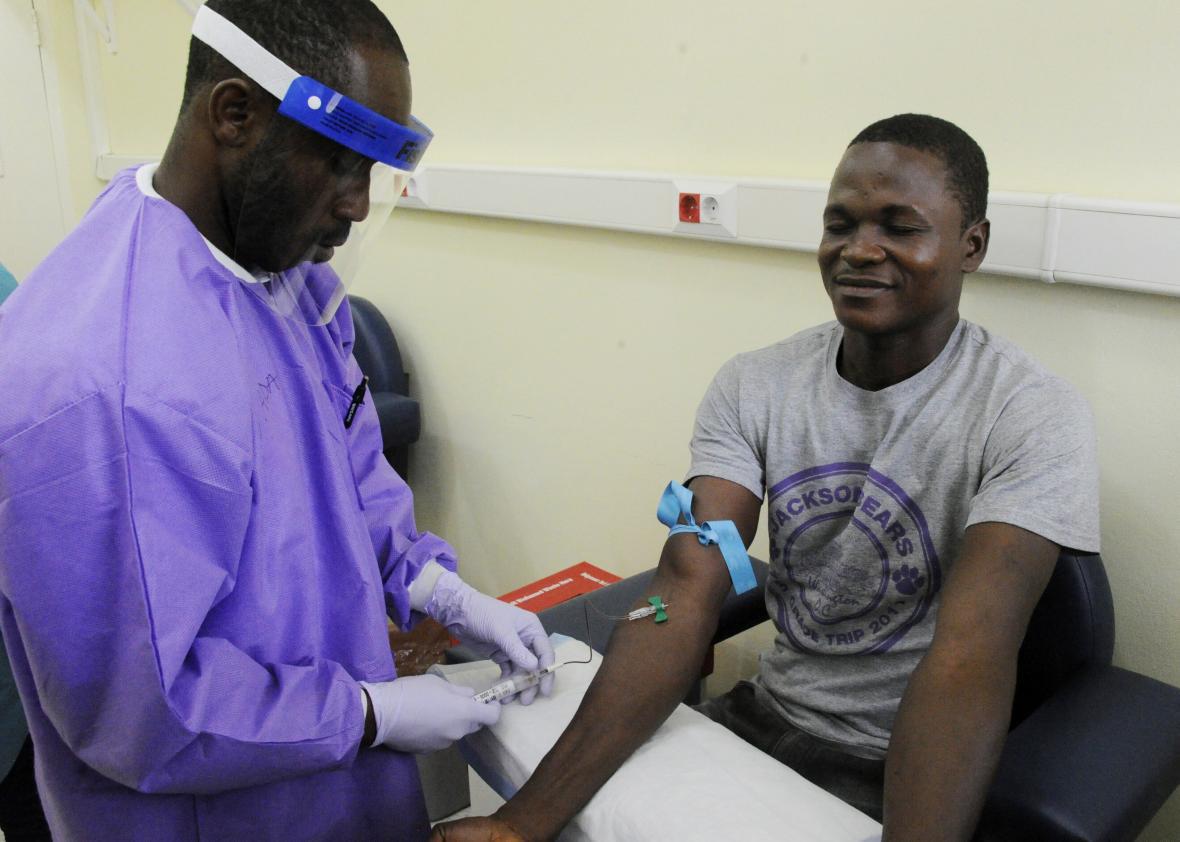

As with other recent public health successes, the campaign against Ebola relied more on education and public safeguards than medical breakthroughs, although a recently developed vaccine has appeared to be highly effective in trials conducted in Guinea since March.

This is all excellent news, but it would be unfortunate if the success in containing Ebola took attention away from the underlying conditions that made the outbreak so disastrous. The Ebola outbreak was a textbook example of what the medical anthropologist Paul Farmer calls an “acute-on-chronic” disaster: It spread so widely and so rapidly thanks to inadequate public health systems, poor sanitation, and years of political violence and corruption that had left people understandably distrustful of government authorities. And that was before the disease killed 7 percent of the health care workers in Sierra Leone and 8 percent of them in Liberia. It didn’t help that the World Heath Organization, the only group in a position to coordinate the international effort, has a budget smaller than many American hospitals, and political priorities have led it in recent years to shift its attention away from infectious diseases.

The WHO’s goal of “getting to zero,” which seemed nearly impossible a year ago, is now within sight. But as Craig Spencer, the doctor and humanitarian aid worker who was infected with Ebola in the fall of 2014, recently wrote in the New York Times, “Staying at zero will require an enormous input of financial and human resources for many months after the last case is diagnosed.”