Update, Aug 20: The National Hurricane Center upgraded Danny to a hurricane at 11 a.m. ET on Thursday, the first of the 2015 Atlantic season. Danny now has an eye, likely the basis for the upgrade, and the latest forecast is essentially unchanged. The original post is below.

Tropical Storm Danny, potentially the biggest Atlantic tropical threat of 2015, has emerged quickly over the past 24 hours or so. The National Hurricane Center expects Danny to grow to hurricane strength by Friday—the first hurricane of the year. After that, there’s a reasonable chance the storm could affect the United States—more on that in a bit.

Danny is currently on track to pass near or through the northeast Caribbean by Monday, where, if it weakens a bit more than officially forecast (though not too much) its rainfall could wind up being a boon to drought-suffering islands like Puerto Rico. Miami-based meteorologist John Morales has a good discussion of this scenario.

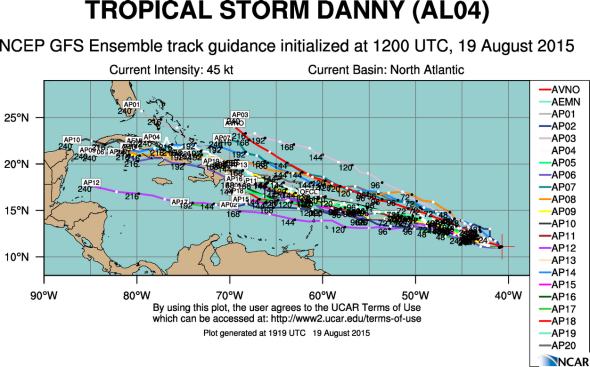

Danny is currently struggling to strengthen and has a tough road ahead of it: Dry air blown in from the Sahara and a pocket of cyclone-killing wind shear over the Caribbean will probably offset the potential boost from increasingly warm water. It’s not possible to confidently predict Danny will even be a storm at all beyond five days from now. On the other hand, it’s perhaps equally as likely that Danny will be a formidable hurricane in 10 days. There are model runs to support both possibilities.

Should Danny survive, there’s reason to believe it could pose a threat to the United States mainland by late August—though I’d rate those chances at no more than 25 percent at the moment. Twelve days is an eternity in tropical cyclone forecasting, and a whole lot can and will change between now and then. In fact, the stunningly photogenic twin typhoons now south of Japan could induce big changes in the North American weather pattern between now and then. Still, if I were living in Florida and there was a one-in-four chance of a hurricane strike within two weeks, I’d want to know about it.

Though it’s borderline meteorological sacrilege to even discuss the possibility of a tropical cyclone landfall so far in advance, a Danny landfall in the mainland United States has the tenuous support of two of the leading weather forecast models, the Euro and the Global Forecast System, the flagship model of the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The Euro, widely regarded as the world’s most accurate weather model, has been relatively consistent over the last several model runs that a weak version of Danny could approach Florida in about 10 days. The GFS has been much more variable, showing a potentially stronger landfall anywhere on the East Coast—as well as the possibility of a much safer curve out to sea. But you should take this information with an Everest-sized grain of salt.

At this point, close weather watchers should be paying attention not to the projected path of the storm itself, but of the large-scale weather pattern that will greatly affect the likelihood of a potential future U.S. landfall. For the last few runs, the Euro has been more insistent on a stronger Atlantic ridge about 10 days from now, which should steer Danny generally more westward, toward Florida or the Gulf of Mexico. The GFS has forecast a stronger trough off the East Coast, and more room for Danny to curve northward out to sea—or to target the East Coast. Again, there’s no way to know how strong Danny will be at this point—it may be just a glorified rainshower—but these clues mean Danny’s future track is a bit more knowable than at first glance.

What’s clear is Florida is long overdue for a hurricane. The last hurricane of any strength to hit Florida was nearly 10 years ago—an unusually long period of time that has also featured massive coastal development. Many people that now live in South Florida have never experienced a hurricane before.

A final clue we have that Danny may in fact eventually target Florida is its similarity with historical storms. Among the top five historical analogs for Danny’s future track is 1992’s Hurricane Andrew, the last major hurricane to strike the Miami area. Andrew also shows up—along with several other historical Florida landfalling storms—in a Washington Post analysis of Danny conducted on Wednesday. Though a name like Andrew sets off alarm bells in many Floridians’ minds, around half of the historical analogs to Danny at this point didn’t affect land at all.

Slate will continue tracking Danny over the coming days, and just to be crystal-clear: there’s no immediate threat to the U.S. mainland at the moment. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t watch Danny closely.