On the day that Secretary of State John Kerry is visiting Cuba to raise the stars and stripes over the U.S. embassy in Havana for the first time in 54 years, Cuban-American senator and presidential candidate Marco Rubio blasted the move as representing “the convergence of nearly every flawed strategic, moral, and economic notion” of Obama’s foreign policy.

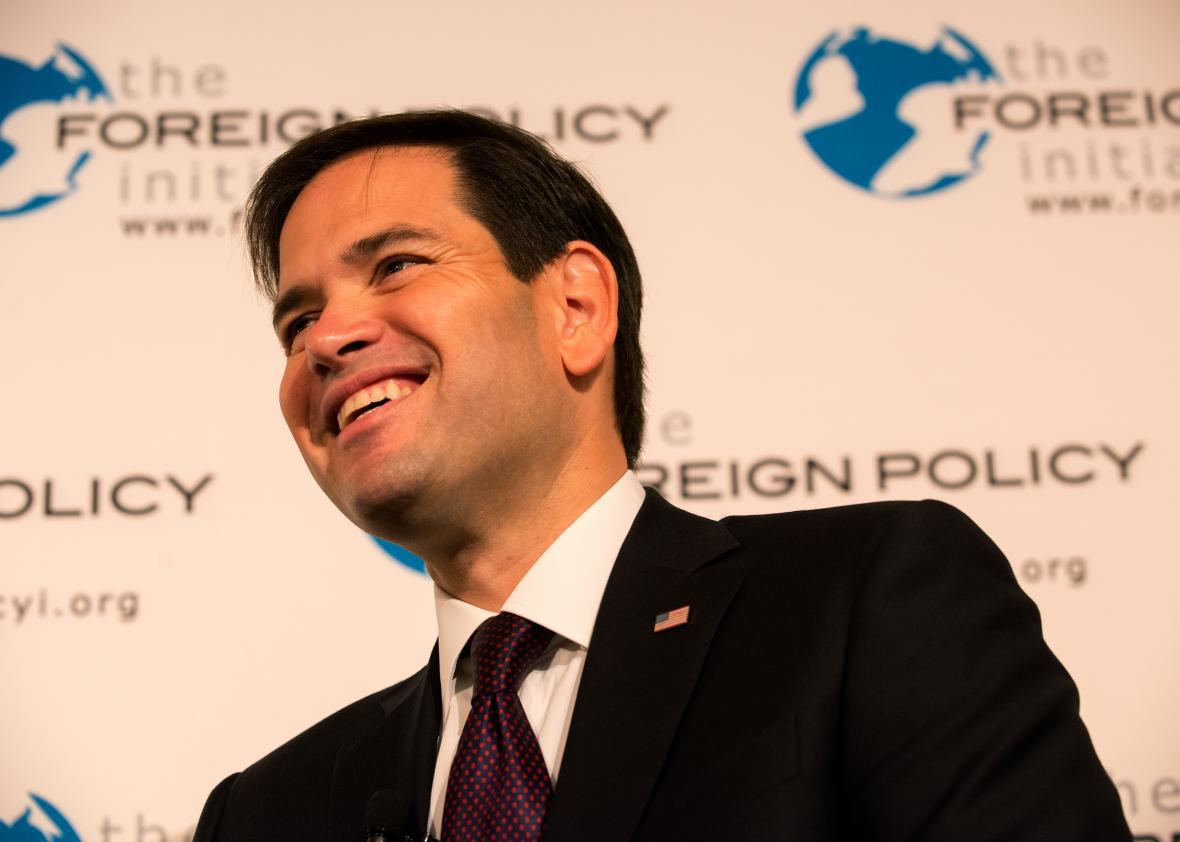

Attacking the rapprochement with Cuba certainly makes sense in the GOP primary, though as I noted last month, it could be risky in the general election with the public increasingly coming around to supporting closer ties with Cuba. But Rubio’s critique is more broad. In remarks released early from the address Rubio delivered this morning at an event hosted by the Foreign Policy Initiative in New York on Friday, Rubio accused Obama of having been “quick to deal with the oppressors, but slow to deal with the oppressed.” He also vowed to roll back the recent diplomatic overtures, should he become president, until “meaningful political and human rights reforms” occur. Likewise, he would revoke the Iran nuclear deal, pass “crushing” new sanctions against Iran, and ensure that any future talks are linked to Iran’s “broader conduct, from human rights abuses to support for terrorism and threats against Israel.”

Every major GOP candidate has promised to rescind the Iran and Cuba deals. But Rubio goes much farther than the others in his emphasis on democracy and human rights. Much more than rival Floridian Jeb Bush, who has been struggling with how to approach his brother’s Iraq legacy, Rubio is running as the standard-bearer of George W. Bush’s neoconservative “freedom agenda”—using American power to aggressively promote democracy overseas.

Though the soundbites are good, it’s an odd choice for Rubio. Much of the Republican party, including to some extent, much of the Bush administration, soured on democracy promotion as the Iraq war grew increasingly unpopular and the policy produced unintended consequences such as Hamas’s 2006 Palestinian election victory. Today, Rubio’s rhetoric stands out in an election where his rivals are citing Egyptian strongman Abdel Fattah al-Sisi as a model world leader. (Like Bush, Rubio isn’t a complete purist: His staunch pro-democracy stance evidently doesn’t extend to America’s allies in the Persian Gulf.) The American public also doesn’t seem too interested in making the world safe for democracy these days: Only about 18 percent say spreading democracy should be one of America’s top priorities. For promoting human rights, it’s 33 percent.

Rubio’s rhetoric does draw a stark contrast with the current president’s skepticism about democracy promotion. Obama famously told an audience in Cairo in 2009 that “no system of government can or should be imposed upon one nation by any other” and, as he nears the end of his term, is finally putting in place something resembling the pragmatic realist foreign policy he ran on.

But Rubio won’t be running against Obama, much as his party will try to frame the general that way. Hillary Clinton may support the Iran and Cuba deals, but as a secretary of state, she was more of a humanitarian hawk than her former boss, pushing for intervention against dictators Muammar al-Qaddafi and Bashar al-Assad. A Clinton-Rubio race offers the prospect of two advocates for using American power to promote democracy and human rights competing for the votes of Americans who are deeply suspicious about the whole concept.