After last Wednesday’s massacre at the Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, Gov. Nikki Haley said the state will seek the death penalty against Dylann Roof, who has reportedly confessed to the shooting. Haley’s condemnation of Roof’s crime was at the very least a welcome departure from the days when similar abhorrent acts were condoned by openly racist elected officials. But Haley’s words aren’t the only way that the government of South Carolina expresses its attitudes. One of those expressions—the Confederate flag that flies in front of its statehouse—has been heavily criticized in recent days, and on Friday the Huffington Post’s Nick Baumann noted another way that the state honors white supremacists: its multiple memorials to 19th-century Gov. Wade Hampton, who was “elected” in 1876 after his party’s death squads suppressed the black vote and killed some 150 people.

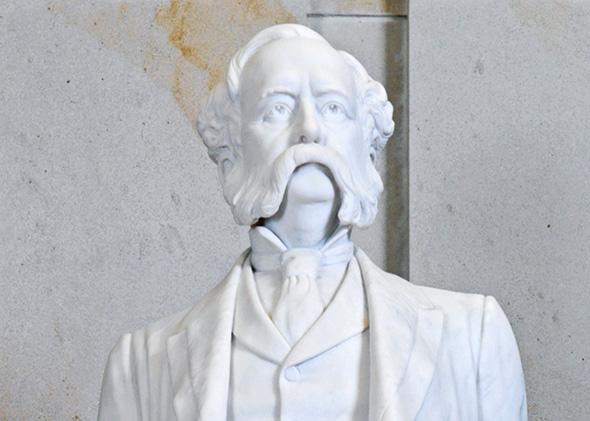

Mother Jones wrote about Hampton in 2013, noting that he’s officially commemorated in the U.S. Capitol by a statue that South Carolina sent to Washington, D.C., in 1929. (The other South Carolina contribution to Statuary Hall celebrates John Calhoun, who was a leading national defender of slavery and states’ right to secede from the Union before his death in 1850.) There’s also a Wade Hampton State Office Building in South Carolina’s own Capitol complex, with a statue of Hampton in front of it.

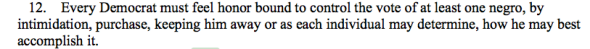

Hampton was a slaveowner and a general in the Confederate army who became governor in 1876—the first Democrat to hold that office after the Civil War—and was later a U.S. senator. His gubernatorial election followed a campaign of terror by Democratic “Red Shirt” groups, who by one account killed some 150 black citizens in the months before voting was held. The groups’ organizing principles explicitly encouraged the murder of Republicans and the suppression of black voters:

SCReconstruction.org

That Hampton benefited from these death squads and took power in part because of paramilitary violence is not incidental to his place in South Carolina’s official history. It’s the only important thing about his place in that history. Per this piece by a South Carolina historian, Hampton himself quickly became irrelevant, a “symbol” who was marginalized by the reactionary radicals who had put him in office. It was the assumption of office itself that Hampton was remembered for as 1876 became memorialized as a year of white triumph. In 1907, South Carolina’s Ben Tillman discussed the year of Hampton’s election on the floor of the U.S. senate:

Then it was that we stuffed ballot boxes, because desperate diseases require desperate remedies, and having resolved to take the State away, we hesitated at nothing … I want to say now that we have not shot any negroes in South Carolina on account of politics since 1876. We have not found it necessary. [Laughter.] Eighteen hundred and seventy-six happened to be the hundredth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, and the action of the white men of South Carolina in taking the State away from the negroes we regard as a second declaration of independence by the Caucasian from African barbarism.

An account written on the 50th anniversary of the election is called Hampton and His Red Shirts: South Carolina’s Deliverance in 1876; it describes “the victorious ride of the Red Shirts” as “one of the most vitally important episodes of the history of the state and country.” Hampton’s statue was sent to D.C. three years after that 50th anniversary.

In a way, the memorialization of Wade Hampton might be even more insulting than the flying of the Confederate flag. The flag’s defenders have convinced many people that they’re not commemorating slavery, just Southern history as a whole. (I don’t believe that argument has merit; I’m just saying others do.) But what else are Wade Hampton’s statue and the Wade Hampton Building besides tributes to his anti-democratic seizure of power? What else could the celebration of a political figure known only for his connection to white supremacist violence possibly be, except an endorsement of white supremacist violence?