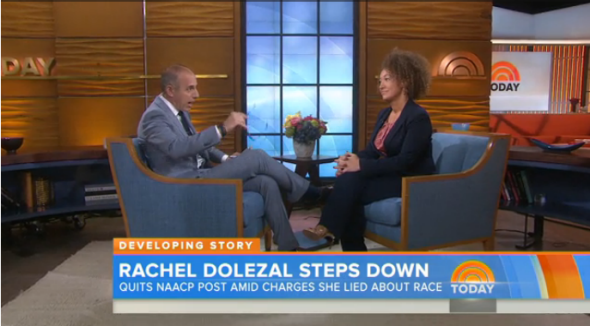

Controversially “black” Spokane NAACP figure Rachel Dolezal told NBC’s Today show host Matt Lauer on Tuesday that her racial identity is “complex” and that she began self-identifying as black as early as age 5—but wasn’t pressed by Lauer about such substantive issues with her credibility as the lack of evidence that the hate crimes she says she was targeted by actually happened or the legal rulings that went against her after she sued Howard University for discriminating againt her because she wasn’t African-American. Here’s the video:

A transcript:

Lauer: Rachel Dolezal, good morning. Nice to see you.

Dolezal: Nice to see you too.

Lauer: You’ve had a busy week. All the headlines, top trending item on Twitter, you resigned your post at the NAACP and you started a discussion on race and what it means in this country. Did this come as a surprise to you or did you always expect the lid would be blown off your story at some point?

Dolezal: The timing of it was a shock. I mean, wow. The timing was completely unexpected. As to the second question, I did feel that at some point I would need to address the complexity of my identity.

Lauer: Let me just say, we can’t talk about the big picture that you have created without talking about the small picture first. Let me just ask you the question in simple terms again, because you’ve sent mixed signals over the years—are you an African-American woman?

Dolezal: I identify as black.

Lauer: You identify as black. Let me put a picture up of you in your early 20s, though, and when you see this picture, is this an African-American woman, or is that a Caucasian woman?

Dolezal: That’s not in my early 20s, but—

Lauer: That’s a little younger, I guess.

Dolezal: I think I was 16 in that picture.

Lauer: Is she a Caucasian woman or an African-American woman?

Dolezal: I would say that visiby she would be identified as white by people who see her.

Lauer: But at the time were you identifying yourself as African-American?

Dolezal: In that picture, during that time, no.

Lauer: Your parents were asked that question this week and they didn’t have any trouble answering it. Here’s what they said: “She’s clearly our birth daughter and we’re clearly Caucasian. That’s just a fact.” Your father went on to say that “she’s a very talented woman doing work she believes in, why can’t she do that as a Caucasian woman, which is what she is?” How do you answer that question?

Dolezal: Well, first of all, I really don’t see why they’re in such a rush to whitewash some of the work that I have done, and who I am, and how I’ve identified, and this goes back to a very early age, with my self-identification with the black experience as a very young child.

Lauer: When did it start?

Dolezal: I would say about 5 years old.

Lauer: You began identifying yourself as African-American?

Dolezal: I was drawing self-portraits with the brown crayon instead of the peach crayon and black, curly, hair, you know, yeah. That was how I was portraying myself.

Lauer: So it started way back then. Rachel, when did you start—and I’ll use the word, you can correct me if you don’t like it—when did you start deceiving people and telling them you were black when you knew their questions were pointed in a different direction? When someone said to you, back then, “Are you black or white?” and you’d say “I’m black,” you wouldn’t say, “I identify as black,” you’d say, “I’m black.” When did you start deceiving people?

Dolezal: Well, I do take exception to that, because it’s a little more complex than me identifying as black or answering a question of “Are you black or white?” I was actually identified when I was doing human rights work in north Idaho as, first, trans-racial, and then when some of the opposition to some of the human rights work I was doing came forward, the next day’s newspaper article identified me as being a biracial woman, and then the next article when there were actually burglaries, nooses, etcetera, was, this is happening to a black woman. And I never corrected—

Lauer: Well, why didn’t you correct it if you knew it wasn’t true?

Dolezal: Because it’s more complex than, you know, being true or false in that particular instance.

Lauer: But the cynics and the skeptics would say, you didn’t correct those reports because it worked for you, because it helped you meet your goals. Is that fair?

Dolezal: I don’t necessarily think that’s fair. I think not just at that time, but before then, too I have had to answer those who have seen me and because I’m a black hairstylist, have styled my hair in many different ways, have been identified as mixed, light-skinned, black, etcetera, and I’ve had to answer a lot of questions throughout my life.

Lauer: You’ve changed your appearance. Your complexion appears darker than it did in the photos of you as a young lady. Have you done something to darken your complexion?

Dolezal: I certainly don’t stay out of the sun, you know, and I also don’t, as some of the critics have said, put on blackface as a performance.

Lauer: Let me address that, because some people have said that the way you’ve changed your opinion [sic] is akin to putting on blackface. And Jonathan Capehart wrote in the Washington Post, “blackface remains highly racist, no matter how down with the cause a white person is.” Do you understand what he means by that?

Dolezal: Absolutely. Absolutely. I have a huge issue with blackface. This is not some freak, Birth of a Nation mockery blackface performance. This is on a very real connected level, how I’ve actually had to go there with the experience, not just the visible representation, but with the experience, and the point at which that really solidified was when I got full custody of Izaiah. And he said, “you’re my real mom,” and he’s in high school, and for that to be something that is plausible, I certainly can’t be seen as white and be Izaiah’s mom.

Lauer: Couple of quick points. There are reports that at times and that at one time in particular you looked at a friend of yours, a guy named Albert Wilkerson, and you told friends of yours that he was your father. He is an African-American man who is clearly not your father. Was that done to enhance your résumé as an African-American woman, or was there another reason for that?

Dolezal: There was another reason. He actually approached me in North Idaho and, you know, we just kind of, we connected, on a very initimate level as family, and—

Lauer: But why point out an African-American man and say “that is my father,” when you know that your father is a Caucasian?

Dolezal: Albert Wilkerson is my dad. Every man can be a father, not every man can be a dad.

Lauer: Your lawsuit in 2002 against Howard University, where you claim you were discriminated against because you were a pregnant white woman. Do you understand how people could hear that and say, “Here’s another example—she says she identified herself as being African-American or black from a young age, but here’s a case where she identified herself as a white woman because it worked for her under the circumstances.”

Dolezal: The reasons for my full-tuition scholarship being removed and my teaching position as well, my TA position, were that other people needed opportunities and you probably have white relatives that can afford to help you with your tuition. And I thought that was an injustice.

Lauer: Would you make the same choices—given all that’s happened, and given the fallout from it, but also the positive side of the discussion that has come out of it, would you make the same choices you’ve made, Rachel?

Dolezal: I would. I would.

Lauer: And what do you want to come out of it? What discussion do you want to prompt?

Dolezal: Well, as much as this discussion has somewhat been at my expense, recently, in a very sort of viciously inhumane way—come out of the woodowork, and—the discussion’s really about what it is to be human, and I hope that that can drive at the core of definitions of race, ethnicity, culture, self-determination, personal agency, and ultimately empowerment.

Lauer: But when you say you would make the same choices—wouldn’t you go back and be a little more transparent about certain things in your life or correct some things that were said about you that you knew to be incorrect?

Dolezal: You know, there are probably a couple interviews that I would do a little differently if circumstances, in retrospect, I knew what I know now. But overall, you know, my life has been one of survival, and the decisions I have made along the way, including my identification, have been to survive and to carry forward in my journey and life continuum.

Lauer: You resigned your position at the NAACP out in Spokane—do you feel you could have been as effective—by the way, you should get a lot of credit, a lot of people feel you breathed new life into that chapter—could you have been as successful, could you have had as big an impact had you been a Caucasian woman as opposed to being identified as an African-American woman?

Dolezal: I don’t know, I guess I haven’t had the opportunity to experience that in those shoes. So I’m not sure, I’m not sure.

Lauer: And finally, your two sons Izaiah and Franklin are here in the studio.

Dolezal: They are.

Lauer: If I were to ask them if you’re a black woman or a Caucasian woman, how do you think they’d answer?

Dolezal: I actually was talking to one of my sons yesterday and he said, “Mom, racially you’re human and culturally you’re black.” And, you know, so we’ve had these conversations over the years, I do know that they support the way that I identify, and they support me. Ultimately, we have each other’s back. We’re the Three Musketeers.

Lauer: Rachel Dolezal. Rachel, thanks for talking to us this morning, I appreciate it.

Dolezal: Thank you.

You can read more on Dolezal’s lawsuit here; a judge and an appeals court both ruled that Howard’s decisions did not impact her adversely and were not racially motivated. Slate’s William Saletan also wrote Monday on other problems with Dolezal’s credibility, including her disputed claims to have been born in a tepee, to have lived in South Africa, and to have been the target of a number of incidents of racially motivated harassment.

Dolezal is scheduled to be interviewed by other NBC and MSNBC hosts over the course of the day, so perhaps some of those issues will be discussed in further depth in her subsequent appearances.

Correction, June 16, 2015: This post originally misspelled Izaiah Dolezal’s first name.