A new report out earlier this month by the global consulting firm Mercer is perhaps the most striking argument yet for fossil fuel divestment, written in the cold, calculated prose of international finance. Its very blunt conclusion: “Climate risk is inevitable. Some impacts on investment returns are inevitable.”

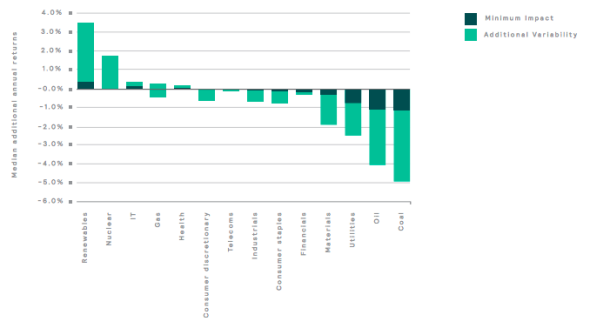

The report looks out to 2050, but its focus on the next 18 months to 10 years—and its emphasis on the unique risks to the fossil fuel industry—makes it especially relevant in the near-term. Specifically, the report advocates for “portfolio decarbonization”—aka divestment—and argues that by reducing your investment exposure to sensitive sectors of the economy (the report identifies utilities, real estate, timber, agriculture, but calls the fossil fuel industry the most risky) you can avoid holding “stranded assets” should world governments put caps on carbon emissions or extreme weather produce escalating damage.

In short, by ridding your portfolio of climate sensitive or fossil fuel intensive companies, you can make the world a better place, and make money at the same time. Climate deniers with fat bank accounts, consider this your chance to change your tune—it’s OK to be selfish, to do it for the money, we won’t blame you.

The Mercer study’s heft is enhanced because it comes with the endorsements by some of the biggest investment funds in the world (with collective responsibility for more than $1.5 trillion), and its release was timed for maximum relevance in advance of December’s global climate negotiations in Paris, which are expected to result in the world’s first international agreement to limit greenhouse gases. The report is the most thorough to date about how various economic sectors will fare under different scenarios of climate action.

The best part of the report is the names it assigns to its climate scenarios: Transformation—corresponding to a world where ambitious near-term limits on carbon result in a rise in global temperatures of no more than 2°C, in line with what scientists and policy experts say is the maximum “safe” amount of warming, Coordination (3°C), and Fragmentation (4°C). These labels provide a very useful way of imagining how the world’s economy and political climate may morph over the coming few decades, and reflects the latest consensus science on the large-scale impacts—from a heroic, immediate, nearly universal rejection of the dangers of continued fossil fuel use in the most ambitious scenario to fragmenting nation-states in a worst-case scenario. (For reference: The world’s current climate policies will likely result in a 3.6°C to 4.2°C rise in global temperatures, a pace that’s actually worse than Mercer’s Fragmentation scenario at the top end.)

Those scenarios roughly correspond with the options currently under consideration by the world’s governments as they craft the blueprint for the meeting in Paris later this year. A 2°C goal is increasingly seen as out of reach by the traditional top-down political process—unless public opinion rapidly shifts. That’s where the world’s investors come in.

Should the world get its act together, it would have a direct benefit for investors. “A 2°C scenario does not have negative return implications for long-term diversified investors at a total portfolio level over the period modeled (to 2050).” That’s finance-speak for: If you want to make money, take ambitious action on climate change.

The corollary to that finding is equally relevant: If you’re an investor in the fossil fuel sector, ignore climate risk at your own peril. Interests in the fossil fuel industry have long been a wrench in the political process of climate-friendly policies, but the Mercer study provides solid evidence that they’re the ones who stand to lose the most money in the next few years, regardless of our collective climate pathway.