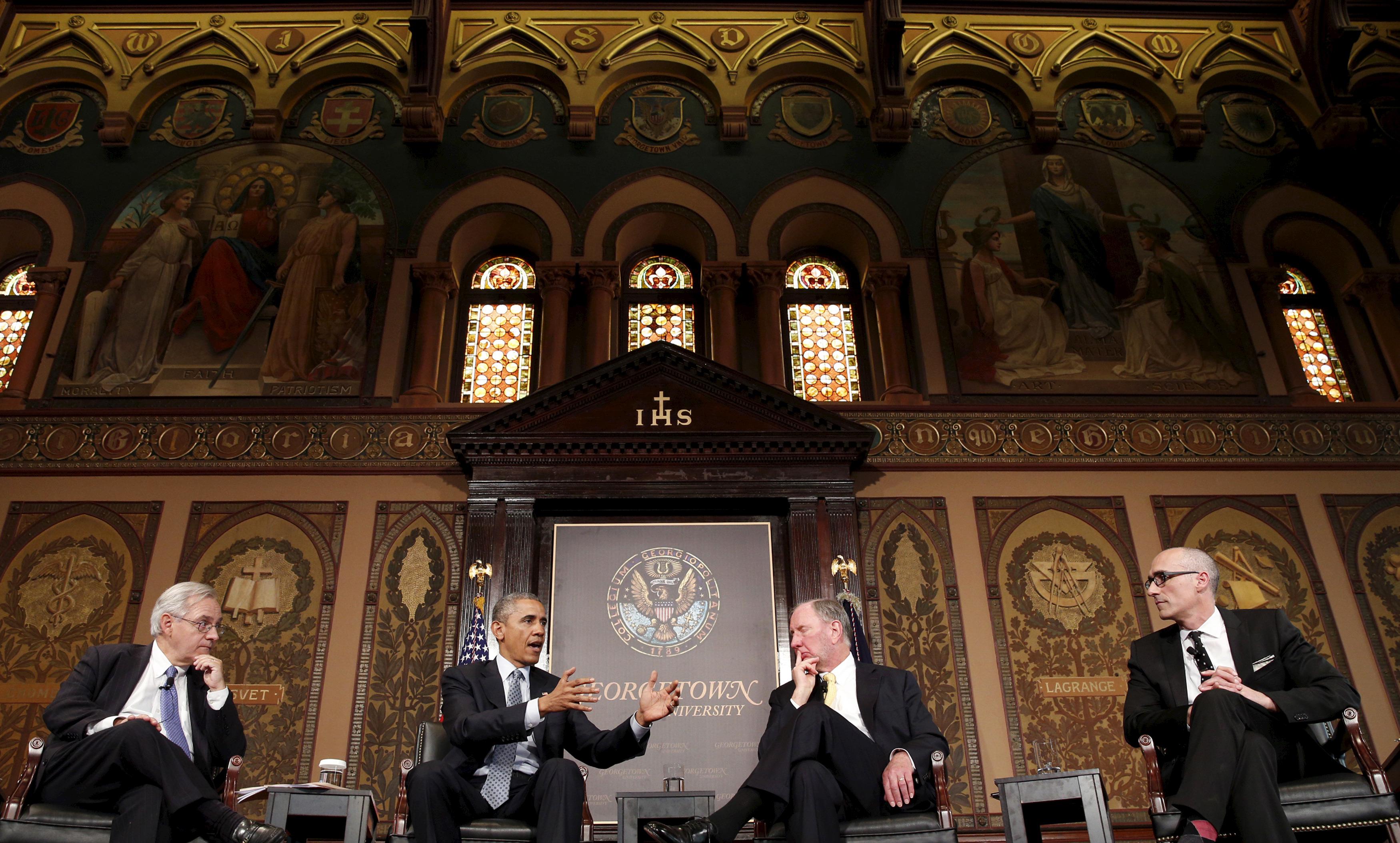

President Obama appeared on a Georgetown-sponsored public policy panel Tuesday and, in addition to making everyone laugh a few times, he participated for about an hour in a discussion of American poverty as it relates to history, culture, and government. Wealth inequality has become perhaps the most ascendant subject of public concern and political debate in the United States, and Obama’s remarks laid out a kind of total liberal theory on the subject—responding in particular to criticism that he’s taken from a number of prominent progressive black writers about the way he discusses poverty and the values of black Americans.

You can read an informative summary of the context here, but in brief: Obama, at events such as historically black college commencements and appearances related to his My Brother’s Keeper initiative for young men of color, has made a point of encouraging personal responsibility, family togetherness, active fatherhood, and the like. A number of writers, including the Atlantic’s Ta-Nehisi Coates, the New Yorker’s Jelani Cobb, and Slate’s Jamelle Bouie, have criticized these comments for playing into the premise that there is something uniquely dysfunctional about black American culture. (Other forums in which you’ll hear such “respectability politics”-type lectures, they say, are Bill Cosby speeches and right-wing-radio discussions of indolent welfare cheats.) At Tuesday’s panel, Coates was mentioned by name and the president was asked to respond to his critiques. Here’s what he said:

On this whole family-character values-structure issue. It’s true that if I’m giving a commencement at Morehouse that I will have a conversation with young black men about taking responsibility as fathers that I probably will not have with the women of Barnard. And I make no apologies for that. And the reason is, is because I am a black man who grew up without a father and I know the cost that I paid for that. And I also know that I have the capacity to break that cycle, and as a consequence, I think my daughters are better off.

And that is not something that—for me to have that conversation does not negate my conversation about the need for early childhood education, or the need for job training, or the need for greater investment in infrastructure, or jobs in low-income communities.

So I’ll talk till you’re blue in the face about hard-nosed, economic macroeconomic policies, but in the meantime I’ve got a bunch of kids right now who are graduating, and I want to give them some sense that they can have an impact on their immediate circumstances, and the joys of fatherhood.

And we did something with My Brother’s Keeper—which emphasizes apprenticeships and emphasizes corporate responsibility, and we’re gathering resources to give very concrete hooks for kids to be able to advance. And I’m going very hard at issues of criminal justice reform and breaking this school-to-prison pipeline that exists for so many young African American men. But when I’m sitting there talking to these kids, and I’ve got a boy who says, you know what, how did you get over being mad at your dad, because I’ve got a father who beat my mom and now has left, and has left the state, and I’ve never seen him because he’s trying to avoid $83,000 in child support payments, and I want to love my dad, but I don’t know how to do that—I’m not going to have a conversation with him about macroeconomics.

I’m going to have a conversation with him about how I tried to understand what it is that my father had gone through, and how issues that were very specific to him created his difficulties in his relationships and his children so that I might be able to forgive him, and that I might then be able to come to terms with that.

And I don’t apologize for that conversation. I think … this is where I agree very much with Bob [panelist Robert Putnam] that this is not an either/or conversation. It is a both-and.

With My Brother’s Keeper set up to be a major part of Obama’s public life after his term ends—and with his general level of candor seeming to rise as that term’s conclusion draws nearer—we can likely expect to hear him address this particular debate much more in the years ahead.

Also, as a side note, it was very odd to watch the president, during Tuesday’s panel, occasionally sitting silently while someone else talked. Like, nothing against fellow panelists E.J. Dionne, Robert Putnam, and Arthur Brooks, who all spoke insightfully and mostly deferred, as was appropriate, to Obama, but they aren’t the president of the United States. We can listen to what they think at, like, all the other panels.