Read all Slate’s coverage of The Jinx.

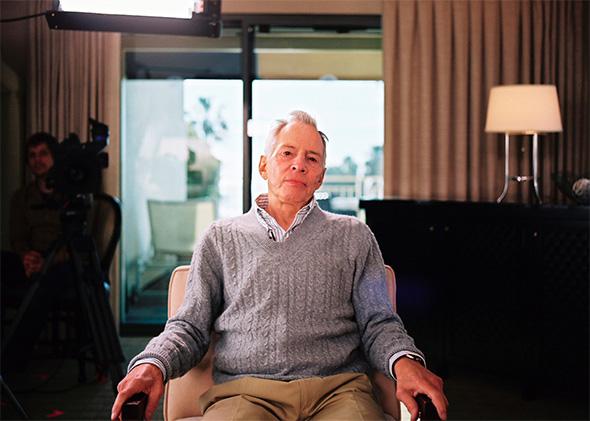

The season finale of The Jinx, with Robert Durst muttering that he “killed them all, of course” in an office bathroom, seemed pretty definitive. But it also left a lot of us scratching our heads over the chronology of what is depicted in the series—who knew what when?—and about the communication that filmmaker Andrew Jarecki and his team had with law enforcement.

Today we’ll be answering as many of our own questions as we can, and updating this post throughout the afternoon. If you have questions you’d like us to try to answer, leave them in the comments.

In Episode 5 of The Jinx, the late Susan Berman’s stepson shows the filmmakers a letter that he has discovered amid Berman’s personal effects. The handwriting on the envelope seems to implicate Durst in Berman’s murder. Did the filmmakers have a legal obligation to make law enforcement aware of the letter, or the audio recording of Durst talking to himself in their bathroom, after they discovered them?

No. Withholding evidence from law enforcement is almost never a crime. “Citizens don’t have a legal obligation to provide information to the police about criminal activity when they have no involvement in the crime itself,” said Daniel Richman, a criminal law professor at Columbia Law School, who has not watched The Jinx. “It’s useful if they do, and good citizens often do, but there’s no legal obligation to turn in a friend, colleague, or interviewee.”

If it turns out that the filmmakers did sit on the evidence—though Jarecki said today that he turned over the bathroom audio recording to law enforcement “many months” ago, and the Susan Berman letter even earlier—you might wonder if they could be charged with “accessory after the fact,” for assisting someone they knew to have committed a crime in order to prevent his or her apprehension. But according to Michael Kraut, a criminal defense attorney and former deputy district attorney in Los Angeles, charging someone with “accessory after the fact” in California —which typically gets invoked when a person hides a murder weapon for a friend or relative—requires a prosecutor to “show the specific intent to assist or aid the person in getting away with the underlying crime.”

“The only way it would be ‘accessory’ is if the filmmakers had made conscious decisions” to help Durst get away, Kraut said. “It would have had to be, ‘We have the evidence that the police is looking for and what we need to do in order to assist Robert Durst is get rid of these tapes and this letter.’ Because then there would be a specific attempt to assist the person.” Short of that, “accessory” wouldn’t apply.

But wasn’t Durst an imminent danger to public safety? Didn’t Jarecki and his colleagues have a duty to do everything they could to bring about his apprehension at the earliest possible moment?

Kraut said the potential dangerousness of a suspected offender doesn’t matter when considering whether a person has a legal obligation to turn over incriminating evidence to police, unless the person who is withholding the evidence belongs to a profession, like psychiatry or the law, in which reporting the imminent commission of crime is mandatory. Journalism is not one of those professions. “If you’re a journalist and somebody sits down with you and does an interview describing the murders they’re about to commit, unfortunately, or fortunately, there is nothing to be done to the journalist” for not passing that information along to law enforcement, Kraut said.

Is Durst’s maybe-confession in the bathroom off limits, as a piece of evidence, because he might not have realized other people could hear him talking?

No, because Durst consented to being wired with a microphone. It might have been different if Jarecki had captured that audio as a result of secretly bugging the bathroom, said Richman. But since Durst willingly wore the mic, everything he said into it is fair game.

But the Times reported last night that Jarecki and his co-producer Marc Sperling “struggled with whether to bring the letter to law enforcement authorities” because, according to Jarecki, their lawyers advised them that doing so “too soon” could lead to them being “considered law enforcement agents in the event of a prosecution, possibly jeopardizing the material’s admissibility in court.” What does it mean to be considered a “law enforcement agent”?

Richman told me he thinks this is a red herring. The standard scenario in which a civilian is deputized as a “law enforcement agent,” he said, occurs when someone is asked by investigators to wear a wire in order to record a suspect saying something incriminating. In those situations, you have “some pre-coordination” between law enforcement and the person they’ve recruited as an informant or collaborator; typically, evidence gathered in that way has to come with a warrant in order to be admissible, which is probably what Jarecki was talking about when he spoke to the Times.

But given that Jarecki and his team were not secretly recording Durst on orders from the police — and that Durst voluntarily agreed to be hooked up to a microphone — Richman says it’s hard to see how the filmmakers would have ever ended up being considered “law enforcement agents,” regardless of when they turned over the Susan Berman letter.

Is it possible Bob Durst was being sarcastic when he said “Killed them all, of course”?

Yes, it’s possible. He reveals himself to be a sarcastic, salty guy throughout the series. And while it might seem strange for Durst to be sarcastic while talking to himself—you’d think sarcasm would require an audience—it’s actually relatively common for people to do this: Just think of the last time you said something like “oh, great” or “just what I needed!” under your breath, for no one’s benefit but your own.

The use of “of course” is consistent with sarcasm, according to Roger Kreuz, an experimental psychologist at the University of Memphis who has studied “lexical markers” typical of sarcastic speech.

“People frequently signal sarcastic intent with lexical markers, such as interjections (gosh, gee), or certain phrases,” Kreuz wrote in an email. “ ‘Of course’ is a common marker of sarcasm because it helps to set off the following remark as potentially nonliteral.”

Kreuz cited a 2000 paper on the vocal cues associated with sarcasm in which a researcher concluded that sarcastic statements tend to be spoken more slowly, more loudly, and at a lower register than sincere statements. What Durst was doing in the bathroom could be characterized as muttering or murmuring, Kreuz said, but the phrase “of course” is “spoken more forcefully and loudly than the preceding utterances.”

That is not definitive, obviously. But there is certainly room for doubt.

Did the LAPD deliberately plan for Durst’s arrest to coincide with The Jinx’s final episode?

Everyone is saying no. Asked if he had made any kind of deal with law enforcement regarding the timing of Durst’s arrest, Jarecki told Good Morning America that it would have been impossible. “A, we don’t have that kind of power. We’re not in charge of the arrest timing, and we had no idea of the arrest timing,” he said. The LAPD’s Deputy Chief Kirk Albanese went even further in an interview with the Los Angeles Times, saying that the show’s revelations had played no role in the department’s decision to carry out Durst’s arrest. “We based our actions based on the investigation and the evidence,” Albanese was quoted as saying. “We didn’t base anything we did on the HBO series. The arrest was made as a result of the investigative efforts and at a time that we believe it was needed.”

* * *

Most recent update: 6:14 p.m.