To date, President Obama’s most substantive response to the killing of Michael Brown has come via the Justice Department, which is conducting two investigations in St. Louis County—one into whether Brown’s civil rights were violated when he was shot, and another into the question of whether area police departments engage in consistent violations of citizens’ civil rights. A recent piece by Ruben Castaneda in Politico speaks to the way the latter investigation might actually work. Castaneda’s article is about Prince George’s County, Maryland, an area that historically struggled with the same kinds of problems being discussed in Ferguson:

In a series of articles published in 2001, the Washington Post analyzed the use of force among county police going back to 1990 and found that officers had shot 122 people and killed 47 of them, giving Prince George’s a higher rate of fatal shootings per officer than any other major city or county police force at the time. I was a reporter in the Post’s Prince George’s bureau at the time and recall that the vast majority of those shot were black; many had committed no crime, the Post found, and 45 percent were unarmed. In one case, two officers claimed they had fatally shot a teenager when he tried to grab their guns, but according to the autopsy, police reports and records from a civil lawsuit, the young man was shot 13 times in the back while lying prone on the floor. Internal police investigations—many of which were inaccurate and misleading—cleared every officer in every one of the 122 Prince George’s shootings, the Post reported.

Unlike Ferguson, Prince George’s County did not lack for black political representatives, but bad blood between police and poorer residents, punctuated by incidents of police brutality, nonetheless led to federal investigations by the FBI and Justice Department. The results included an overhaul of the way the police trained and deployed their canine unit in addition to a number of other steps:

… in January 2004 the Justice Department and the county signed an agreement that called for the police department to put in place broad reforms, including internal investigations into every incident in which a police officer shoots someone; a board of police commanders to review such shootings; a prohibition on officers investigating any incident in which they themselves used any kind of force; and an improved computer database to flag officers who use force multiple times. The police department also said it installed video cameras in 600 cruisers to document the actions of officers on the street.

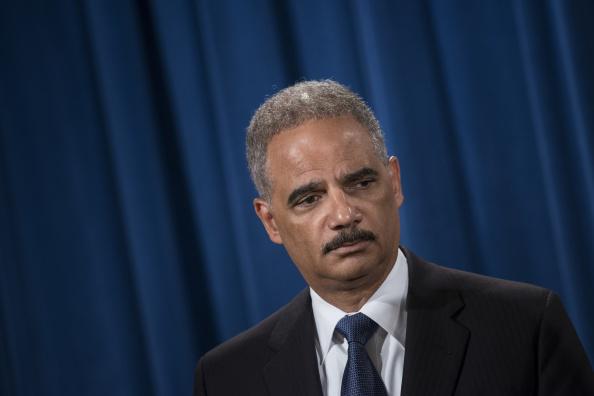

Castaneda writes that police-community relations have since improved significantly and that incidents of violence against unarmed suspects have dropped. Of course, this being reality, fatal police-involved shootings have not disappeared entirely, and one of Castaneda’s main sources—an investigator who works with defense attorneys—says she has “not seen a lot of change.” What’s more: Castaneda writes that one significant factor in changing police behavior was the criminal conviction of an officer who released a canine against an unarmed homeless man. It was a consequence that other officers could not ignore. Which is to say that in Ferguson, no matter what reforms and retraining programs the federal government puts into place, much could still depend on the potential prosecution of officer Darren Wilson. And getting a jury conviction of Wilson is not something Eric Holder or Barack Obama, for all their power, can guarantee.