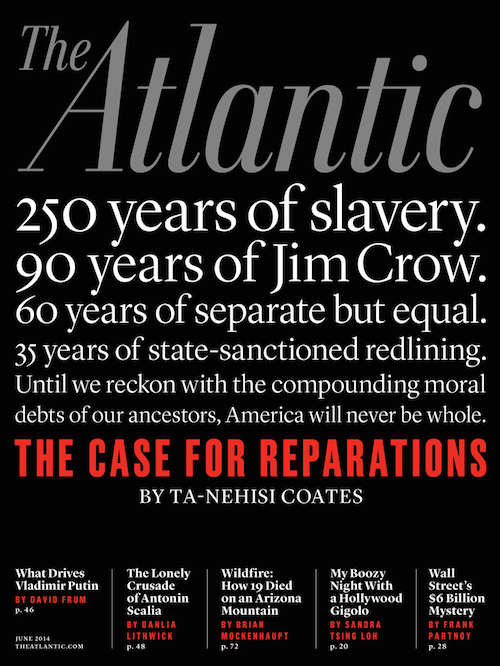

Last night the Atlantic posted a 15,000-word piece by writer Ta-Nehisi Coates that frames 400 years of black experience in the United States as a case for reparations. Given Coates’ reputation and the explosiveness of the subject—and the way that the Atlantic teased the piece in past days like it was a blockbuster movie—expectations were high, and the piece, by most accounts so far, fulfills them.

For this American history major’s money, there are three aspects of Coates’ article that make it more than just an effective summary of existing thinking and scholarship (which it is) and into a groundbreaking piece in its own right:

1) Its emphasis on black workers creating wealth from the 1700s through sharecropping through the industrial postwar 1950s—and its corresponding lack of emphasis on the emotional harms of discrimination. Coates writes about the fortunes made through the efforts of black Americans using terms like “assets,” “profits,” and “economic foundation.” Consider this striking fact:

In 1860 there were more millionaires per capita in the Mississippi Valley than anywhere else in the country.

The piece simultaneously documents the variety of methods, from the obvious (slavery) to the less so (home ownership policies) by which the government of the United States has prevented black citizens from keeping that wealth and passing it down generationally. American debates over race and poverty often revolve around “giving” “our” money to an impoverished group out of sympathy for their condition. Coates barely acknowledges that motivation. His piece is about giving someone back the money that they made in the first place.

2) Its emphasis on the coordinated, federally-backed effort to keep blacks from owning homes after WWII. Slavery happened a long time ago, right? Coates doesn’t use the phrase “slavery reparations” or “reparations for slavery” in his article. Its central sections are about the way that the wealth of banks and the federal government in the post-WWII era (much of it, incidentally, created by blacks in the labor force and secured by blacks in the armed services) was channeled to white homeowners, creating a stable white middle class while blacks were kept (legally!) from having access to mortgages and middle-class neighborhoods.

It was the [federal-government-backed] Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, not a private trade association, that pioneered the practice of redlining, selectively granting loans and insisting that any property it insured be covered by a restrictive covenant—a clause in the deed forbidding the sale of the property to anyone other than whites. Millions of dollars flowed from tax coffers into segregated white neighborhoods.

Again Coates preemptively undermines one of the most reflexive arguments against reparations. No, you personally didn’t own slaves or keep a black person from voting, his piece says to white readers, and you probably have never rejected a black person from a job because of their skin color. But if you or your parents were alive in the 1960s and got a mortgage, you benefited directly and materially from discrimination.

3) The stories of people who are still alive. Coates’ essay is framed by reported profiles of black men and women, still living, who have been subject to what is essentially extortion and forced segregation throughout their lives. It’s another reminder that the eradication of separate-but-equal and the March on Washington should not have cleared the existence of racial discrimination from the national consciousness.

The piece persuasively (and seemingly effortlessly) turns the issue of race in America into a pressing discussion about work, wealth, and theft rather than an unresolvable grudge-match about bygone guilt. (Please read it here!) Of course, it also has the words “reparations” and “slavery” in it, so you can assume that a lot of discussion about it will go like this:

Yep.