Over the past two weeks, the leaders of the two most important nations of the world won contests that will ensure that something close to continuity will reign for the next four years. In both China and the United States, extremists who would love to recreate the Cold War’s dynamic will be left on the sidelines mostly, still able to stir trouble but not actually steering policy.

This is a good thing. By any measurement, the U.S.-China relationship and rivalry—a rival-ationship, perhaps—is the most important in the world. During the 2012 election campaign, sadly, it apparently was necessary to cater to dimwits who think that China is the new Evil Empire and that the economic relationship is a one-way street, benefiting only China and undermining the United States.

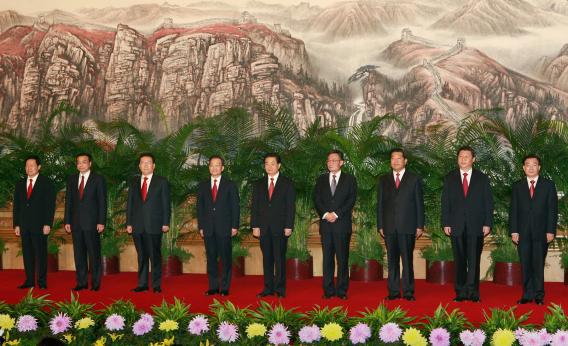

Similarly, in Beijing, as China’s Communist Party weighed the composition of the new leadership announced Thursday, no one dared show any signs of weakness (or even reason) when it came to nationalistic fetishes like the disputed islets of the South China Sea or demands by Westerners for improved human rights.

But hopefully, we now get down to business. With the US election decided and China’s new leader, Xi Jinping, officially installed, the time for simplistic views has passed. Before the US enters yet another “political cycle,” genuine, frank conversations and compromises on both sides need to take place, and both Obama and Xi need to explain to their respective populations why getting along is the only way to avoid catastrophe.

Contrary to the rhetoric of the right—and of the trade-union left, too—China’s dependency for growth on the American market, along with commercial innovations the U.S. regularly produces, puts Beijing at a disadvantage in the long run.

With its increasing dependence on imported energy, persistent internal unrest, and a susceptibility to bouts of inflation, China’s pushmi-pullyu relationship with America presents terrible dilemmas for the country’s communist leadership.

The fact is, in spite of the Chicken-Littlism of the right, China’s rise as an economic giant, and eventually a military and diplomatic competitor to American power, is taking place under terms the United States can influence and even harness to its own advantage. So far, in the three decades since China opened its economy to capitalism and began its breakneck sprint toward world-power status, the United States has failed to develop a coherent strategy to leverage these advantages—particularly in innovation, technology, and intellectual creativity.

Such a strategy would require Washington to invest heavily in its own economic and creative strengths, as well as adjust its military posture in the Pacific to accommodate Chinese interests without sparking conflict. It would also require Washington to insist on greater Chinese participation in international diplomacy and peacekeeping and prepare American allies in Asia for the realignment of power that looms ahead.

To understand how we got here, we need to go back a few decades. In 1989, a deep freeze enveloped U.S.-China ties after the Tiananmen Square massacre. Gradually, isolation gave way to a paternalistic approach as the United States held out “rewards” like most-favored-nation trade status or membership in the World Trade Organization as incentives for China to continue opening its economy to competition. All of this made sense early on, when China’s home market was largely closed off to foreign products and foreign direct investment was limited to joint ventures with state firms.

However, the approach lost its effectiveness in 1997 when China absorbed Hong Kong’s dynamic banking sector. Suddenly, more and more Chinese trained in United States and other foreign universities chose to return to their homeland. Supercharged by the mix of long-term economic planning, first-class financial acumen, and cheap credit, China’s growth accelerated, and it became clear that its emergence as an economic giant was inevitable.

But too many assume they know where this leads. In fact, the exact shape of the future geopolitical order remains very uncertain. Some view the United States and China as rival standard bearers of competing ideologies—democratic market capitalism and repressive state capitalism—bound to clash in the 21st century just as fascism, communism, and democracy did in the previous one. But clinging too fervently to this belief risks creating a self-fulfilling prophesy, particularly in a world where the balance of power in Asia and elsewhere is in transition and where none of the old talking shops, from the United Nations to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations to the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, are ready to offer a credible forum for mediating disputes.

The issues that receive obsessive attention from each side—the undervalued Chinese currency, disputed territorial claims in the South China Sea, and China’s gradual modernization of its military—raise the risk of a sudden miscalculation that could have tragic global consequences. What’s more, the black-and-white view of this relationship obscures the fact that the United States retains the upper hand militarily and economically.

Washington should be plotting a future based on the awesome strengths of American free society and economic productivity. Instead, it scapegoats China, its chief competitor, for striving to lift its population out of destitution. Since the 2008 financial crisis, the United States has acted like a football team that can only play defense. Case in point is the running dispute over China’s currency, the renminbi, or RMB, which is also known as the yuan. The People’s Bank of China—the country’s central bank—has kept the RMB low in order to maximize the competitiveness of Chinese products. The dispute pits those who think a strong RMB would make U.S. manufactured goods more competitive globally against those who see it as a relatively small issue in a very complicated relationship.

The larger problem is not about exchange rates but “global imbalances”—the fact that China’s consumers save at enormous rates and consume little compared with the spend-crazy, credit-addicted West. Getting Chinese consumers engaged in the global economy would do far more to employ American workers than a readjustment of its currency rates. Rather than building a mountainous surplus based on export earnings that it ploughs into U.S. Treasuries and other investments, China could be recirculating that money domestically and stimulating a consumer boom that would produce a positive effect for every major manufacturing power on Earth.

Of course, there are enormous structural impediments to this readjustment—for instance, Chinese banks effectively operate as funnels, sucking up much of the savings in Chinese households and transferring them (via bank balance sheets) to the corporate-state sector, underwriting its investments in massive infrastructure and other projects, and keeping consumer spending weak. Reforms to this system, which barely figure in US-China joint communiqués, would mean that more Chinese-made products would stay in China, with fewer dumped cheaply into foreign markets.

But such subtleties are lost on American legislators. Rather than focusing on ways to maintain and extend the US lead in high-end manufacturing, US politicians have waged a doomed battle to protect manufacturing industries like textiles and furniture that stand no hope of supporting what the American workforce considers a decent life. As a result, Congress has pressured for an appreciation of the RMB to be the featured ‘task’ of recent US financial talks with the Chinese. Granted, the United States has also established an annual bilateral economic summit that attempts to broaden the conversation to such areas as energy and climate change, but with US jobless rates hovering near 9 per cent, the pressure to scapegoat isn’t letting up anytime soon. The ‘all eggs in one basket’ foolishness of this is clear, and the idea that China will relent given the potential cost to its fragile domestic stability seems unlikely.

Like all powers emerging from long periods of backwardness, China wants to make the most of its labour cost advantages while they last — something that giants of nineteenth-century American capitalism understood very well. Fair play, which figures high in the rhetoric of contemporary American politicians, featured not at all in the development of American capitalism’s march to global dominance.

Imagine a China run by a democratically elected government. Given the likelihood that an appreciation of the RMB would cause mass layoffs as foreign factories switch to other, even cheaper Asian producers like Bangladesh or Vietnam, any government claiming to act in the name of its citizens would resist outside pressure to allow the RMB to appreciate.

Meanwhile, neither the Chinese nor other foreign holders of US Treasuries are under any illusion about the ultimate aim of US policy: a covert devaluing of the US dollar, thus drastically reducing the value of the enormous investment China and other US creditors hold as their shares of the US national debt.

This lack of a ‘grand strategy’ in America’s approach to China shows up in minor trade and commercial disputes. Recently, a bid by the Chinese telecommunications company Huawei Technologies to buy the American firm 3Leaf was dropped under pressure from the US Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, a Cold War-era body founded to prevent sensitive technology from falling into Soviet bloc hands. In 2007, the same panel stopped Huawei buying an Internet routing company, 3Com, which was ultimately purchased by US giant Hewlett-Packard.

There will be times when such actions make sense. Some of China’s largest firms remain deeply entangled with the state and China’s military. And not all of China’s proposed investments have caused political fights. China’s Lenovo bought IBM’s PC business in 2006, and the huge construction firm, China State Construction Engineering Corporation, is a major contractor on the reconstruction of the San Francisco Bay Bridge and has won contracts for work on New York City’s subway and other large infrastructure projects.

But China’s FDI in US corporations remains tiny — a paltry $791 million in 2009, compared with the over $43 billion invested in China by American firms that same year. With China’s appetite for such investments likely to increase by up to eight times in the next decade, the United States would be foolish to continue warding off such money particularly given that these investments would help, over time, support US exporters and offset the enormous trade deficit the United States has been running with China for decades, amounting to $273 billion in China’s favor in 2010.

China’s great manufacturing complexes now dominate global markets across vast product lines, including appliances, consumer electronics and consumer durables like sporting goods, clothing, toys, furniture and textiles. Yet China lacks something that its nineteenth-century peers had in spades: innovators. Even in 2010, the year China officially overtook Japan as the world’s second largest economy, no Chinese brand could be called a household name in any Asian market, let alone in the wider world. Something is retarding China’s transition from copycat manufacturer to innovative top dog. The kind of manufacturing that accounts for nearly all of China’s export earnings relies on low-cost inputs, including labour, as opposed to the value-adds of quality and technology that underpin an advanced economy’s manufacturing sectors, notably in Japan, Germany and the United States. The combination of a nineteenth-century business model and a twenty-first-century pseudo-communist political repression does not foster creative thinking.

The problem might be solved in the long term by investment in R&D and reforms to China’s economic incentives and education system — indeed, Japan suffered from precisely these problems early on in its emergence from the depths of destruction after World War II into a postwar economic powerhouse. But economists also suspect that the centralized nature of China’s government will prove a lasting liability, allowing the United States and other advanced economies to maintain their lead in high-tech goods for far longer than might otherwise be the case.

This underscores a deeper dilemma. China’s brute strength in manufacturing is based on the simple, and possibly unsustainable, deal that the Communist Party made with its urban elites — namely, that it will keep incomes rising and leave these urban elites alone to make money as long as they keep their political aspirations to themselves. But as more and more Chinese in the vast, poor interior clamour for their own piece of the pie, wages will rise and demands for safety and environmental codes will erode competitiveness. When this happens and jobless workers get angry, the urban elites may demand a greater say in their own government. But by then, the rural millions may not have much patience left.

China is by no means doomed to remain a smokestack power. Increasing investment in science and technology, now running at about 1.5 percent of the GDP, puts China at the top of the table among emerging economies in terms of R&D spending, and fourth overall behind only the United States, Japan and Germany. But the country’s mediocre higher educational system, demographic and political challenges and corruption suggest that this will be more of a Long March than a Great Leap Forward.

Take the problem of demography. China certainly cannot be described as suffering from a shortage of people, but it is suffering from an acute shortage of young people, thanks to its enforcement of one-child population control policies since 1979. China has enjoyed a larger ‘demographic dividend’ (extra growth as a result of the high ratio of workers to dependents) than its neighbours. But the dividend is near to being cashed out. Between 2000 and 2010, the share of the population under 14 — future providers for their parents — slumped from 23 percent to 17 percent. China has around eight people of working age for every person over 65. By 2050 it will have only 2.2. Japan, the oldest country in the world now has 2.6. As the Economist magazine pointed out recently, China is getting old before it has got rich.

The US figure, according to Census Bureau projections, is 3.7 working people per retiree — and the trend will go gently upward. Indeed, of the countries that will rank as the world’s largest economies later in this century, only the United States, Brazil and Turkey have managed to avoid acute ‘dependency ratio’ problems. For the United States, a relatively high birth rate and a much more open approach to immigration have saved it from the worst of the crisis.

In 2011, the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) reported that, due to a number of changing economic realities — including rising salaries and economic expectations among Chinese workers, new labour, environmental and safety regulations abroad, the higher cost of energy required to ship products halfway around the world, and the US market and the uncertainties of political risk in these places — the cost benefits of producing in Asia no longer automatically outweigh the risks. Indeed, the BCG report predicts a ‘renaissance for U.S. manufacturing’ as labour costs in the United States and China converge around 2015. Anecdotally, the effects can already be seen in new plants created in the United States and in some instances in which plants set up abroad a generation ago to leverage lower labour costs have relocated back to America. This has started to happen, too.

If the main factors in these decisions were labour costs and the weak dollar, the victories would be Pyrrhic. ‘Inputs’ — energy, transportation, raw materials and other production costs — will fluctuate. But, the decisive advantages include innovative management and production techniques, savings on transportation costs, lower political risk and corruption, and the productivity and relatively high skill levels of the American workforce.

The US economy, with its potent, creative corporate sector; transparent bureaucracy; world-beating universities; and highly skilled labour force, does not have to bow down to China. It can compete and adjust to the arrival of China and to the billion-odd other middle-income workers being added to the global economy in other emerging-market countries by stretching its lead in high-end, knowledge-based commerce. The true danger for the United States does not lie in predatory Asia sweatshops. Instead, this danger lies in bumbling, for political reasons, into an overtly hostile stance that puts the world’s two most powerful nations on course for a war so terrible that no nation, regardless of its choice of economic or political models, will survive it.