Can a democratic system function efficiently in an advanced economy in our modern, globalized world? A system based, say, on a couple of 18th century documents updated occasionally by nine people in black robes and a two-chambered legislature that must devote at least as much time to the raising of funds to re-elect itself? I think it can—eventually—but not everyone agrees.

This is the conversation that I have continually found myself in during three weeks of conversations at universities, public forums, bookstores, think tanks, and corporations. People are skeptical, and they are right to be.

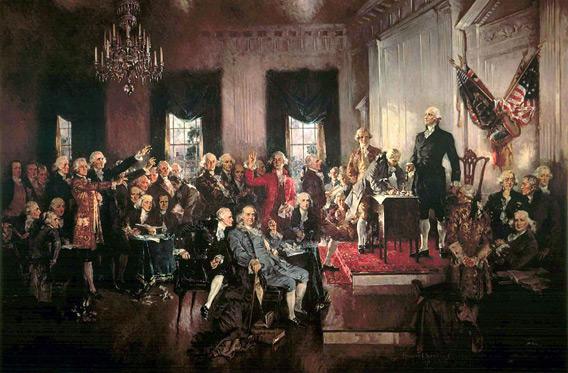

Would Jefferson, Madison, Hamilton, and other American architects of our own system necessarily design precisely the same system that grew out of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and Bill of Rights if they faced today’s realities? At a time when the primary challenges facing the U.S. include increasing inequality of income distribution; a collapse of critical infrastructure; and the rise of other global powers that will compete for resources, influence, and power, would the system (just for instance) insist that elections take place every two years at the national level, thus ensuring a nearly permanent stage of politicking?

(If the obvious answer eludes you, consider an alternative question: Would these statesmen have left slavery in place during the administration of an African-American president? Or given the “purse strings of government” to the branch run in part by people like Rep. Paul Ryan, who said last summer that a default on the U.S. national debt might even be a good thing.)

So you have to wonder, what would the system look like in such circumstances? The conversation on this point was particularly poignant at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism last night, where I shared a stage with Thomas Edsall, author of The Age of Austerity: How Scarcity Will Remake American Politics.

Edsall, like me a longtime journalist who could stand and watch the train wreck of our national dialogue no more, puts forward a radical proposition—that the future will be an increasingly ugly fight between the rich and poor in this country over dwindling resources.

Summed in in Michiko Kakutani’s review in the Times last might, this means a “ brutish future stands before us,” with Republicans and Democrats “enmeshed in a death struggle to protect the benefits and goods that flow to their respective bases”— a “dog-eat-dog political competition over diminishing resources.”

Here, for once, was someone gloomier than me—or at least than my book’s ominous title. Edsall, who spent decades as the leading political reporter of the Washington Post, sees the failure of our economy to recover from the collapse of 2008 as a symptom of our political dysfunction rather than merely exacerbated by it.

This is a nuanced difference—I tend to disagree in that I view the adoption of the theory or radical economic deregulation by the Democrats in the late 1990s as the tipping point—the moment where reason gave up the ghost and the U.S. financial system—with all its global entanglements—invariably spun wildly onto its own doomed course.

That fateful decision by the Clinton administration—the idea that they couldn’t fight Reaganomics, so they’d join it—was not the result of division in our politics; it was the result of cynical, tactical positioning by Clinton’s team ultimately dubbed “triangulation.” It worked wonders at the polls, but ultimately it also pulled the sentries from the economic gates.

To me, scarcity is not the primary thing preventing the two or three back-room deals that are necessary to recalibrate U.S. spending and agree on a “stimulate now, balance later” approach to our economic problems. The answers are there—just as they answers to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has been clear for years. It is a matter of political will.

The real problem is the civil war raging within the GOP, whereby a weakened elite (wiling to make a deal) has lost control of its nativist, willfully ignorant right flank. Nothing less than electoral failure will bring that war to an end, and in spite of early polls showing a race in November, I think failure is precisely what awaits the GOP in November. There is no teacher, after all, like failure.

Over the past few weeks, though, this question keeps arising. Is the job of running the world’s largest economy and most powerful military simply too complicated for our 18th-century template?

In Mountain View, Calif., I gave a Google Talk that involved an audience wired to reject the idea that anything can be too complex to solve. But there, too, skepticism about the human element—particularly when ensconced in Washington—prevailed. Why, one member of the audience asked me, would any logical foreign country continue to invest its money in U.S. Treasury bills—the “loans” that enable our deficit spending—given the conduct of our political class?

It is an excellent question—and, as I’ve been saying, in Beijing and Kuala Lumpur, Brasilia, Moscow, Mumbai, and Jakarta, financial specialists are hard at work trying to create an alternative to the U.S. dollar as the world’s reserve currency.

It may be that only then, when that alternative exists, that the deciding votes in the GOP’s civil war, and the wider battle over America’s future, are cast. If so, those votes will be cast by people who do not share a need to put America’s best interests first.

Then again, that sounds a lot like our current political elite.

The sad truth is that in a modern, complex world, citizens have to hope that they have elected representatives who will, if only rarely, take a far-sighted approach to issues even if it bucks popular opinion. The average person simply does not have time to consider the relative value of free trade accords, talks that would demilitarize outer space, proposals to unwind Fannie and Freddie, and countless other problems that any honest attempt at solving requires serious focus.

In theory, the job of our congressional representatives in particular should be to avail themselves of the enormous resources of the federal government to learn all that is possible to know about every issue before them and to cast the vote that facts compel them to cast.

In fact, most of our representatives and senators lazily take the advice either of their party’s leadership—calibrated almost entirely for electoral purposes—or from wealthy special interests of one ilk or another—calibrated entirely for the benefit of a corporation, political cause, or micro-segment of the population.

Fixing problems like this, it seems to me, will require something other than a well-meaning former community organizer, nine judges, and a Congress of self-interested fundraisers. It will require American voters to finally demand reforms not merely to policy but to our system of government. For whatever Edsall and I disagree on, we agree on this: Our political system is broken and incapable of fixing itself.