We live in an era, according to many people I respect, in which tenets of capitalism that a decade ago seemed unshakably part of the 21st century are being challenged. Ian Bremmer’s upcoming book, “Every Nation for Itself: Winners and Losers in a G-Zero World,” builds on a theme we’re both fond of: that the competition between state capitalism and market economics is very real, but that it need not split the world into Cold War-like warring tribes if managed properly.

Big “if” in there, of course, especially in the midst of a GOP presidential primary season. And, truth be told, good reasons exist for the free market side to be defensive these days, too. Capital flows now favor the Emerging Markets (EM), and in many cases demographics do, too (though not with respect to “one-child” obsessed China, but that’s another story).

The ability of China and other EM powers to generate growth while still intervening furiously in their domestic markets has chipped away at the western dogma that argues such states will invariably be swamped by inefficiencies and poor bureaucratic choices and fall victim to a growth-and-jobs killing sclerosis.

The irony that these same market purists led the world’s largest economy off an economic cliff in 2008 is interesting to point out but less important in the long-run. Crises happen, and intelligent societies emerge from them better equipped to avoid making the same mistakes.

But the great, universal question hanging over global economy today is this: will a middle income EM country – a Brazil, Turkey, Indonesia or South Africa – or even a small, resource rich country aspiring to improve its lot - have a better chance moving up the economic food chain and avoiding cyclical catastrophe by emulating China’s state capitalist model, or the west’s liberal market democratic form of capitalism?

Ian’s book and many others argue convincingly that many states – from “usual suspects” like Venezuela and Iran, to more surprising ones like South Africa, Saudi Arabia and Egypt – effectively already have adopted some form of China’s state capitalist model.

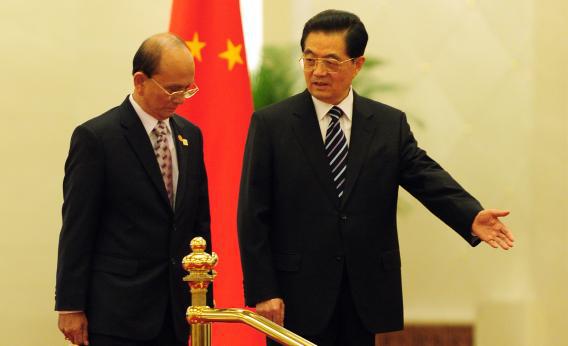

But the slide goes both ways. I find it strange that few have remarked on the amazing flip-flop occurring in Myanmar (Burma) right now. This country, led by a paranoid, repressive pro-Beijing military junta since the late 1980s, has come of out its shell. Six months ago, Myanmar’s President U Thein Sein visited Beijing, where Hu Jintao promised to “protect Myanmar’s interests” and signed a treaty of friendship. But Myanmar has since moved in some very un-Chinese directions.

Yet, upon emerging from the darkness chosen to release political prisoners, Myanmar appears poised to go West rather than stick with its patrons to the north. Over the next few months, it looks likely to elect a civilian-led government and set in motion sweeping economic and political reforms.

After decades of stagnating as a resource-rich, repressive backwater under Beijing’s wing, the Burmese Spring, as some have inevitably called it, has led to calls in the US Congress for a lifting of US sanctions, and a high-profile visit from Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in December.

More importantly, Myanmar has entered into serious talks with two institutions that will insist that it play by liberal market economic rules: the IMF and World Bank. The military junta, which appears to have gone out of business after last year’s elections, had stopped payment on previous debts. A recent visit by a joint delegation stressed that the arrears would have to be dealt with before new international financing became available – but Myanmar’s mining and energy revenues should make that academic.

But the two multinational lenders already have started helping Myanmar’s government modernize its banking and regulatory sectors, and a World Bank vice president said if the arrears are cleared up and the April 1 elections are judged to be fair, the taps will open quickly.

“If President Thein Sein maintains the trend of opening Myanmar economically and politically — and there is reason to believe he will — such bottlenecks could be removed, external finance could flow, and Myanmar could experience an economic boom as labor productivity and living standards catch up with its Southeast Asian neighbors,” writes Vikram Nehru of the Carnegie Endowment’s East Asia Forum.

Other promising signs have emerged, too. Japan, which suspended aid to Myanmar when Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi was arrested in 1993, has just pledged to reengage there. The government late last year also suspended a Chinese-funded $3.6 dam construction project that had local residents and environmentalists alarmed – another sign that what the average person thinks may finally matter there.

All this is progress, of course, for Myanmar’s long-suffering citizens. Free and fair elections are hardly a given, and the country continues to suffer from serious ethnic frictions. But viewed from the standpoint of global influence, this looks a bit like Sadat ejecting his Soviet advisors back in 1977. the decision of such a long-standing Chinese ally to essentially reject China’s most basic practice – buying off the middle class with economic reforms while insisting on complete control of political discourse. Ever since then, China’s fortunes have waned in the country it practically owned until recently, and relations – both locally and diplomatically – have suffered.

Maybe it is better that Asia has not yet sunk into a zero-sum mindset – no headlines read, “Rangoon to Beijing: Drop Dead,” or maybe “Obama Sets Pick, Myanmar Rolls.”

But beneath the happy headlines about Suu Kyi’s release and an apparent springtime for democracy there, the deeper story is of a brewing competition for influence between cash rich China and fickle Uncle Sam from the Atlantic Coast of Morocco right around to the 38th parallel in the Korean Peninsula. And from Algeria to Zambia, in that sense, a race of sorts has already begun.

Michael Moran is Director and Editor-in-Chief of Renaissance Insights, at Renaissance Capital, the emerging markets investment bank. Follow him on Twitter, subscribe to his Facebook feed, or preorder his book, “The Reckoning: Debt, Democracy and the Future of American Power,” coming in April from Palgrave Macmillan.