Sprint: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days by Jake Knapp with John Zeratsky and Braden Kowitz is a new book in which the Google Ventures’ design partners share the step-by-step process behind the “sprint” methodology that Knapp created to help companies such as Google, Slack, and Blue Bottle Coffee design new products and services in the space of a workweek. In the excerpt below, the authors detail how the Wright Brothers inspired the sprint process and how the methodology that they outline in the book is being adapted in companies, classrooms, and government agencies across the country.

It’s a freezing December day, overcast and blustery. Two co-founders lean close to each other and exchange a few words. One week ago, their latest prototype failed, but they think they know why. They’ve made a few fixes, and this morning, both men feel confident. After more than three years of building and testing, their crazy long-term goal might be in reach.

A cutting 20-mile-per-hour wind curls fine spray off the sand. Most people would say the weather sucks, but the two men hardly seem to notice. If their prototype fails, they’ll still learn something, and they know that only five people will see it happen. They make the final preparations and check in with the observers. It’s time to begin.

And it works. For 12 glorious seconds, everything goes right. Their second test is another success, and the third. Hours after beginning, they run the fourth and final test of the day, and boom! Four-for-four. In the last test, the prototype works for a full 59 seconds, and the co-founders are elated. It’s 1903, and Orville and Wilbur Wright have just become the first humans to fly a powered aircraft.

It’s easy to think of the Wright brothers as otherworldly historic figures whose famous flight was an unparalleled work of genius. But as a reader of this book, you might recognize the methods and hard work that got them off the ground.

The Wright brothers started with an ambitious, practically crazy goal. At first, they didn’t know how to get there. So they figured out which big questions they needed to answer. In 1899, the Wrights did their own version of “ask the experts” by corresponding with others who had tried to fly and writing to the Smithsonian Institution for technical papers on aerodynamics. They found existing ideas by researching kites and hang gliders, observing birds, and studying boat propellers. Then they combined, remixed, and improved.

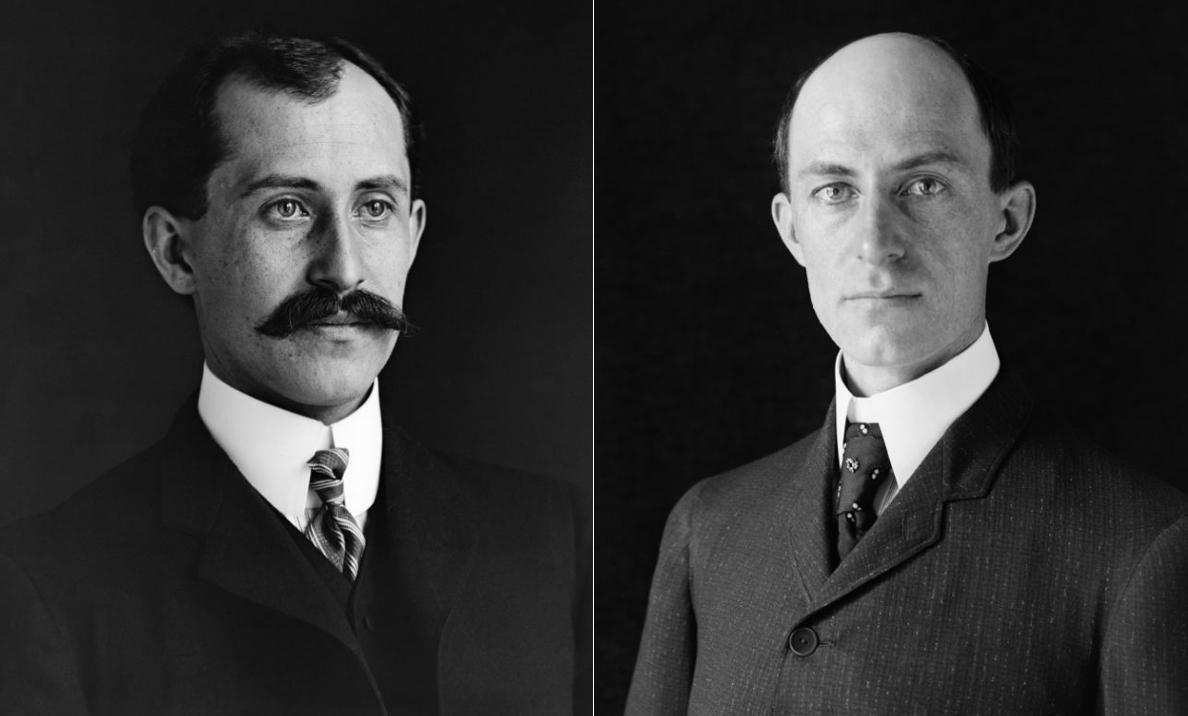

Orville Wright and Wilbur Wright/Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons

For the next few years, they made progress by staying in a prototype mindset. One step at a time, they isolated challenges and broke through obstacles. Could they get enough lift? Would a person be able to keep an aircraft steady? Could they add an engine? Along the way, they crashed. A lot. But each time, they used a new prototype purpose-built to answer one specific question. They remained fixed on the long-term goal, and they kept going.

Sound familiar? The Wright brothers didn’t use sprints to invent the airplane. But they used a similar toolkit. And they used it, and used it, and used it. Forming a question, building a prototype, and running a test became a way of life.

Google Ventures design partner Jake Knapp conducting a “sprint.”

Google Ventures

Sprints can create those habits in your company. After your first sprint, you might notice a shift in the way your team works. You’ll look for ways to turn discussions into testable hypotheses. You’ll look for ways to answer big questions, not someday, but this week. You’ll build confidence in one another’s expertise and in your collective ability to make progress toward ambitious goals.

The phrase “ambitious goal” might sound like corporate-speak or the headline of a bad inspirational poster. But we shouldn’t be embarrassed to have ambitious goals at work. Each of us has only so much time in a day, in a year, and in our lives. When you go to work in the morning, you should know that your time and effort will count. You should have confidence that you’re making a difference in real people’s lives. With the techniques in this book, you can bring focus to the work that matters.

Since 2012 we’ve run more than 100 sprints with startups. That’s a big number, but it pales in comparison to the number of people who have taken the sprint process and used it on their own to solve problems, reduce risk, and make better decisions at work.

Co-author John Zeratsky (far right) seated on the couch midsprint.

Google Ventures

We’ve heard about sprints in classrooms. At Columbia University in New York City, professor R.A. Farrokhnia wanted to teach his business and engineering students how to run a sprint, but—with the typical class schedule—there was no way to get a solid week of time. So he hacked the system. Farrokhnia found a free week at the end of summer term and organized an experimental “block week” class that would stretch across the full five days. The typical classroom at Columbia is arranged in auditorium seating, not ideal for a sprint, so he tracked down classrooms being remodeled and hauled in some whiteboards. The sprint was on.

In Seattle, two high school math teachers named Nate Chipps and Taylor Dunn used a sprint to teach their students about probability. The students created high-fidelity prototypes of a board game in one class period. In the next class, they watched as their peers played the prototype game, making notes about which ideas worked and which didn’t. By the time they turned in their final assignment (a revised version of the game), they’d observed how the probability principles operated in real life.

Google Ventures

We’ve heard about sprints in all kinds of contexts. Legendary consulting firm McKinsey & Co. began running sprints, as did advertising agency Wieden+Kennedy. The sprint process is used at government agencies and nonprofits, as well as at major tech firms, at companies such as Airbnb and Facebook. We’ve heard sprint stories from Munich, Johannesburg, Warsaw, Budapest, São Paulo, Montreal, Amsterdam, Singapore, and even Wisconsin.

It’s become clear that sprints are versatile, and that when teams follow the process, it’s transformative. We hope you’ve got the itch to go run your own first sprint—at work, in a volunteer organization, at school, or even to try a change in your personal life.

You can run a sprint anytime you’re not sure what to do, or struggling to get started, or dealing with a high-stakes decision. The best sprints are used to solve important problems, so we encourage you to pick a big fight.

Throughout the book, we outline a handful of unconventional ideas about how to work faster and smarter:

- Instead of jumping right into solutions, take your time to map out the problem and agree on an initial target. Start slow so you can go fast.

- Instead of shouting out ideas, work independently to make detailed sketches of possible solutions. Group brainstorming is broken, but there is a better way.

- Instead of abstract debate and endless meetings, use voting and a decider to make crisp decisions that reflect your team’s priorities. It’s the wisdom of the crowd without the groupthink.

- Instead of getting all the details right before testing your solution, create a façade. Adopt the “prototype mindset” so you can learn quickly.

- And instead of guessing and hoping you’re on the right track—all the while investing piles of money and months of time into your ideas—test your prototype with target customers and get their honest reactions.

At Google Ventures, we invest in startups because we want them to change the world for the better. We want you to change the world, too. To that end, we’ll leave you with one more thought about the Wright brothers, this one from their friend John T. Daniels, who was present at their famous flight on Dec. 17, 1903.

“It wasn’t luck that made them fly; it was hard work and common sense,” said Daniels. He went on: “Good Lord, I’m a-wondering what all of us could do if we had faith in our ideas and put all our heart and mind and energy into them like those Wright boys did!”

Reprinted from the book Sprint: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days by Jake Knapp with John Zeratsky and Braden Kowitz. Copyright 2016 by Simon & Schuster, a part of CBS Corporation.