Vimeo co-founder Zach Klein started the Cabin Porn Tumblr in 2010 as a way to document his own adventures in building a forest community called Beaver Brook in upstate New York with friends. Soon people around the world began contributing photos, and the website has grown to feature more than 12,000 cabins, treehouses, yurts, sugar shacks, and other handmade structures that perfectly capture the age-old, modern-day urge to escape to a cabin in the woods. A new spinoff book of the same name features photos of some 200 of those structures, as well as 10 stories about the people who made them.

Here at the Eye, Klein shares an excerpt called “How to Live 30 Feet in the Air” written by Wired correspondent Steven Leckart about a young man who returned to his childhood home in Sandpoint, Idaho, to build the treehouse bedroom he always fantasized about having in his backyard.

Photo by Noah Kalina

Ethan Schlussler laid down his ax. He stood back and looked at the mammoth pile of firewood sitting on the hill behind his mother’s barn. After four hours of bucking grand fir, he’d finished splitting enough wood to last them a month. It was an early afternoon in June 2013, and the summer sun wouldn’t be setting until close to 9 p.m. Now what? Ethan wondered. Glancing up at the trees, he suddenly remembered that when he was younger he’d dreamed of building a treehouse.

In 1999, when he was 8 years old, Ethan and his family moved to an 8½-acre plot on the outskirts of Sandpoint, Idaho, near the Kaniksu National Forest, a lush 1.6 million acres that spill across Idaho, Washington, and Montana. Nestled along a creek, the family’s land was full of fragrant evergreens, conifers, and deciduous trees: grand fir, white pine, hemlock, western larch, western redcedar, cottonwood, Douglas fir, Engelmann spruce, and Rocky Mountain maple.

By the time he was 10, Ethan was a proficient climber. At 12, he hammered together his first “treehouse,” a modest little platform with no walls or roof that still sits 20 feet up in a birch tree near his mother’s cabin. The family lived in a two-bedroom A-frame with a corrugated aluminum roof and wood-burning stove. It was cozy but small. So when he was 18, Ethan began fantasizing about constructing a separate bedroom for himself in a towering grand fir neighboring the cabin. He grabbed a pencil and started sketching. He drafted a few floor plans but then got distracted and left for college to study photography.

Photo by Noah Kalina

When he returned home a few years later, he started working for a local contractor: felling trees, landscaping, renovating homes, and constructing guest cabins. He also helped his mother maintain their forest, which included clearing trees and chopping a lot of firewood.

As Ethan chopped firewood that afternoon in June 2013, he thought about time. It had been five years since he’d abandoned his plans to build a new bedroom. “A lot of people have dreams; then they get a job and have a family. And then they get to be 40 or 50 and suddenly realize all their dreams just fell by the wayside. I didn’t want that to happen to me,” he recalls. “Twenty years from now, I didn’t want to be like, Why didn’t I ever build a treehouse when I had the chance? I realized I had the time and the energy and the resources. So I just decided right there: OK, I’m gonna do this.”

Photo by Noah Kalina

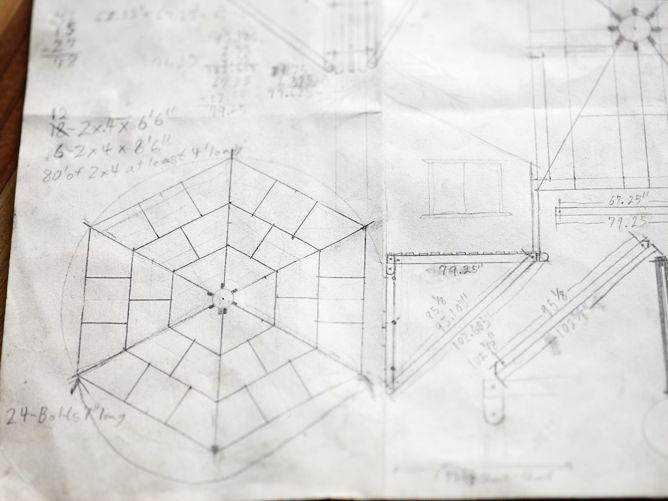

Ethan walked around, surveying the trees. He climbed a few before settling on a tall, healthy larch. He found his original drawings and started sketching new ones.

The experience of working for the local contractor had increased his knowledge of construction. He wanted to avoid drilling holes and inserting bolts into the tree. A common and dependable way to fasten lumber to a trunk, bolting doesn’t necessarily harm or stunt a tree’s growth, but it can. Ethan was determined to find an alternative. He was also determined to engineer something unique. “I intentionally ignored the rest of the world when it comes to treehouses,” he says. “I did no research whatsoever. I wanted to build it entirely from my own ideas. I wanted it to feel like it was entirely mine. If you’re not looking at a book telling you how to do it, then every possibility is open to you.”

Photo by Noah Kalina

Photo by Noah Kalina

That afternoon, he quickly got to work sketching ideas. He devised a clamping system—a series of 2-by-4s arranged vertically around the trunk and held in place by a metal cable. With enough pressure and friction, the 2-by-4s would stay fixed, at least theoretically. From there, the boards would become an anchor—the skeleton to which he could attach the frame of his treehouse.

Ethan hacked together a small prototype to test his clamp design on a little tree, 3 feet off the ground. He drilled a small hole into each board, threaded the cable through, pulled it tight, and then welded a bolt to the cable ends. The boards didn’t budge. So he climbed on top of the boards, hugged the tree, and jumped up and down over and over. The boards still didn’t budge.

Photo by Noah Kalina

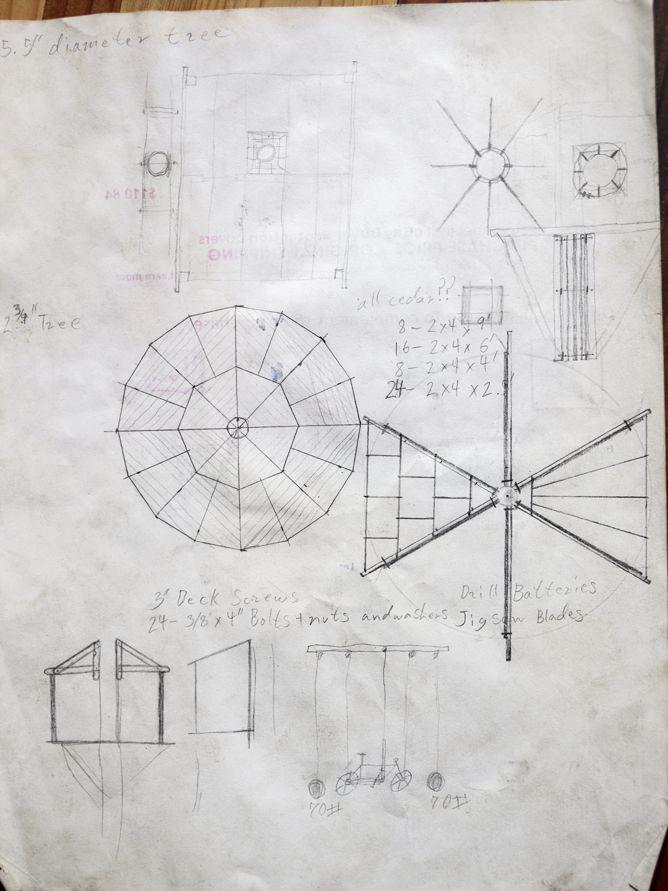

Ethan returned to his larch. He measured the trunk’s circumference and began calculating the specifications for a larger clamp. With the sun starting to dip behind the tops of the evergreens, he moved inside and began drawing floor plans. In time, his design evolved from a circle to an octagon, and then to a hexagon. Fewer sides would make for a lighter, less complicated frame.

For two weeks, Ethan worked his job five days a week from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. Every afternoon, he’d return home and work on the treehouse until 9 p.m., or whenever it got too dark to work. He borrowed a lumber mill from his childhood friend Aza, who helped him cut some of the boards. Ethan opted for cedar, because it’s lightweight, highly resistant to rot, and one of the prettier woods available on his mother’s property. He built the clamp and six triangular support braces to hold up the floor and walls. Then he borrowed a 32-foot extension ladder, which determined the height of the treehouse; he simply climbed to the top of the ladder and marked a spot on the trunk. A rock climber and self-described adrenaline junkie, Ethan has little concern for heights.

Photo by Noah Kalina

He slung each of the 60-pound support braces over his shoulder and carried them up the ladder one at a time. He used a ratchet strap to hold everything in place on the tree until he was ready to secure the clamp permanently with logging cable and bolt the braces to it. It took a week of afternoons to get everything installed, then a day and a half to lay the flooring just right. He wanted the floor to echo the treehouse’s hexagonal shape. To create the right pattern, he needed to adjust the lengths and angles of the boards gradually. Getting all the angles to match was maddening; every tiny little variation from the previous cut just kept getting exaggerated. On day one of the flooring, Ethan spent more than eight hours in the tree. Without walls or a roof, the treehouse was so light that the platform swayed back and forth whenever he moved. When he got back down on solid ground, he felt seasick.

Photo by Noah Kalina

Once the flooring was finished, he started hosting treehouse parties. Around the edge of his 100-square-foot platform, he constructed a temporary railing. Sometimes six friends would join him to sleep in the tree.

Throughout July and August, the rest of the treehouse was designed on the fly. Ethan built the roof before the walls. He decided to include a porch. Most importantly, he thought about having to climb that 32-foot steel ladder repeatedly. In three months, he’d already ascended and descended the ladder hundreds of times. His knees were tired. And it was boring. What he needed, he realized, was some kind of elevator. Maybe a small platform with a hand crank and winch? Ethan wasn’t sure. He kept thinking.

Photo by Noah Kalina

His friend Aza suggested a pedal-powered elevator. Aza thought it’d look cool to orient the bike vertically with both wheels touching the tree trunk—the cyclist would literally ride up the tree. Ethan thought a horizontal orientation would be easier to build and operate; plus, it’d still look cool to sit on the bike and float upward, almost as if he was defying gravity. He commandeered his mother’s old Diamondback and bought five large pulleys and about 150 feet of metal cable. He built most of it in a day and then tinkered for a week. He attached two cables—one to the front of the frame and one to the back—so that the bicycle wouldn’t tip forward or backward.

At first, pedaling was exceptionally difficult. So Ethan removed the big sprocket from the crankset and welded it onto the back wheel hub to make the gearing lower. He also found an old water tank sitting in a junk pile along with scrap metal near his mother’s garage. He attached the tank to the cabling, figuring that with enough water, it’d be heavy enough to function as a counterweight to help pull the bike up as he pedaled. He was right. It worked.

Photo by Noah Kalina

Watching visitors pedal themselves up into the treehouse is gratifying for Ethan. He knows the elevator adds a sense of whimsy to the whole structure. But he’s equally thrilled about his one-of-a-kind clamping system. Although the treehouse has gradually inched down the trunk—2 feet in one year—the structure itself is holding up just fine. Plus, he’s made adjustments that have slowed its descent. As the treehouse keeps settling, Ethan believes, the trunk will grow around the clamp, helping to prevent further sliding and keep everything in its right place. “And, you know,” he says, smiling, “only time will tell if I was right or wrong.”

Photo by Noah Kalina

From the book Cabin Porn by Zach Klein with Steven Leckart; feature photography by Noah Kalina. Copyright © 2015 by Zach Klein. Reprinted by permission of Little, Brown and Company, New York, NY. All rights reserved.