Martin Salisbury’s new coffee table book, 100 Great Children’s Picture Books, is an eccentric survey of works from around the world that are remarkable for beautiful, innovative, or original art and design.

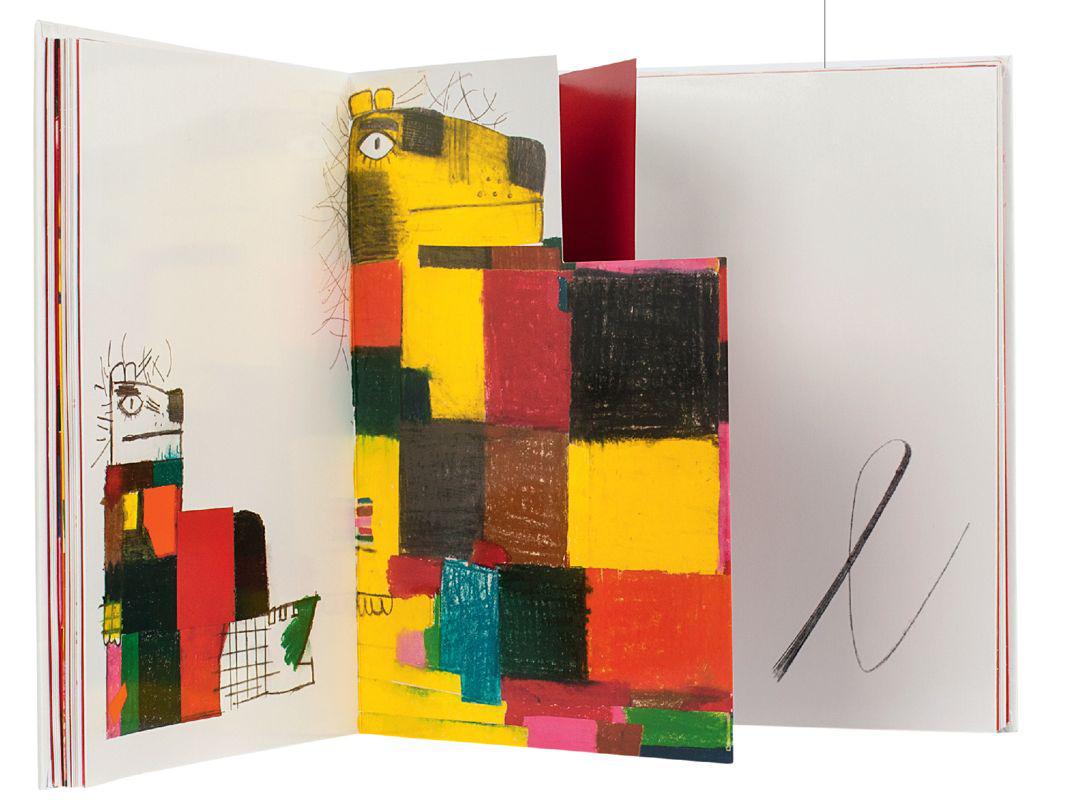

Salisbury says that Pacovská’s innovative work “plays with the physical make-up of the book as an object, as a total experience that is not rooted in the visualization of text or narrative.”

Courtesy of Laurence King

Salisbury teaches illustration at the Cambridge School of Art at Anglia Ruskin University in the U.K., where he created and directs the U.K.’s first master’s program in children’s book illustration. The book is a celebration of the resonance that the images in children’s books have on our culture and our lives.

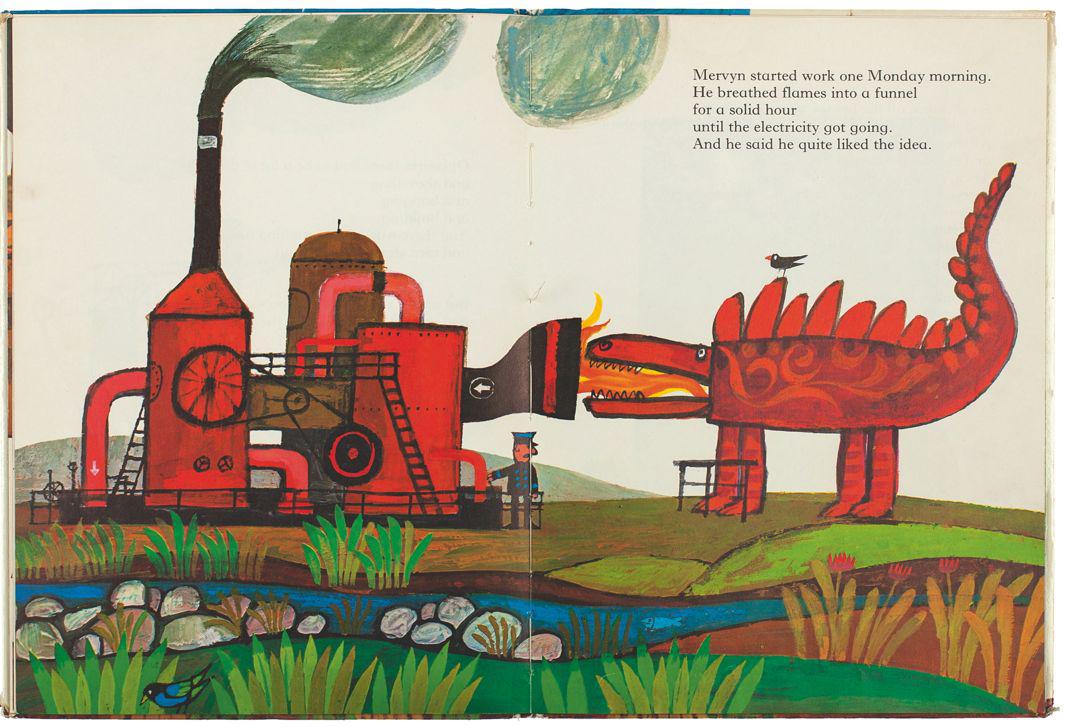

Courtesy of Laurence King

The professor acknowledges that his diverse, worldly, and highly personal selection is a subjective list; many of the books featured are from his own collection or those of friends and colleagues. “I am of course very aware that, as a multi-modal form of communication, the successful picture book is about much more than good art and design,” he writes in the book’s introduction. “This selection, however, is first and foremost about good art and design, and is made entirely on that basis. It aspires to deliver a visual feast for those who love the picture book.”

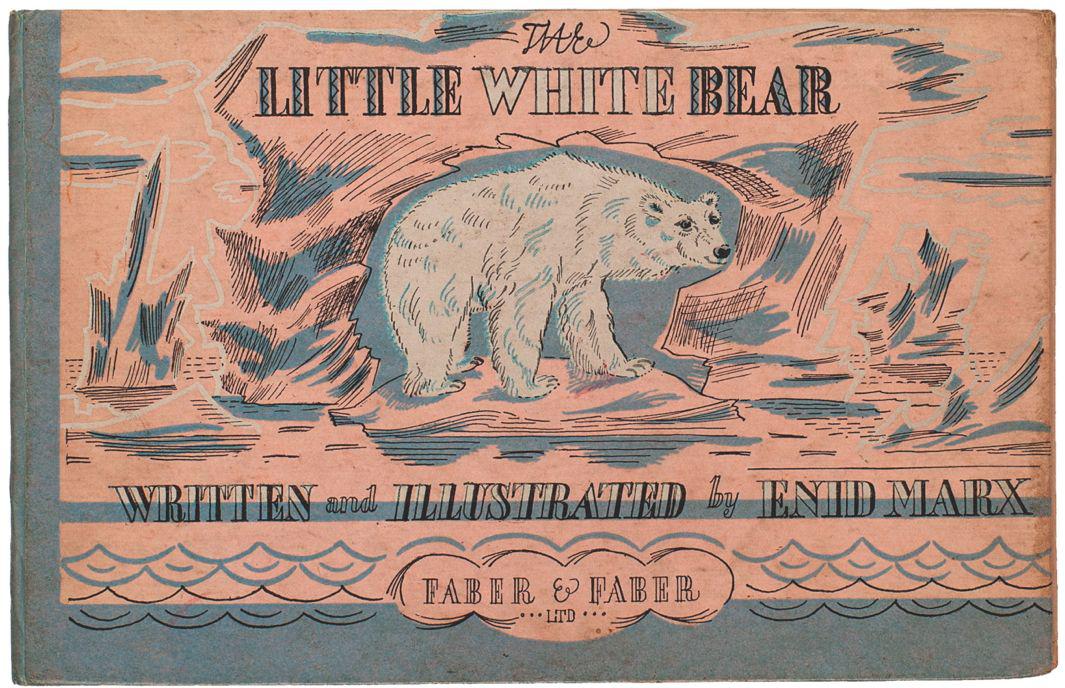

The cover of The Little White Bear by Enid Marx, a distant relative of Karl Marx. The book was published in London in 1945. Many of her books had wartime themes and were printed on coarse wartime paper, giving texture to the illustrations.

Courtesy of Laurence King

Salisbury points out that despite our obsession with screens, the printed picture book as an object continues to thrive. Current digitization of the artistic process, he says, has only made them more sought-after and valued.

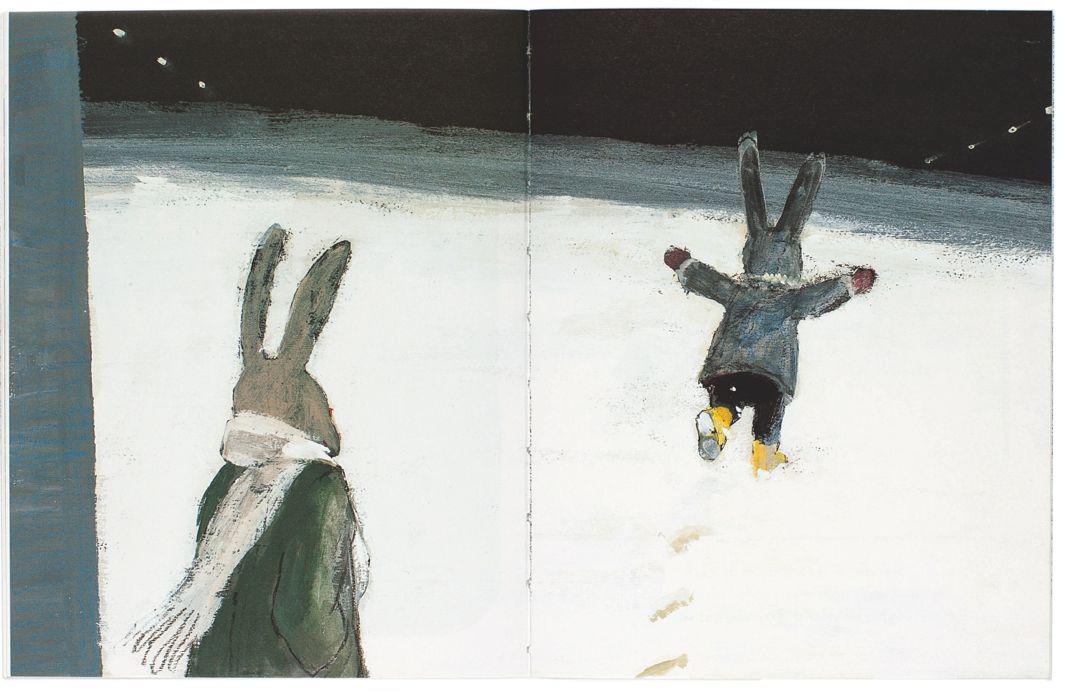

Courtesy of Laurence King

He adds that institutions have begun to recognize the ties between children’s book illustration and cultural heritage, among them the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, Massachusetts; Japan’s Chihiro Art Museum and the Brian Wildsmith Museum of Art; Seven Stories National Centre for Children’s Books in England; and London’s House of Illustration.

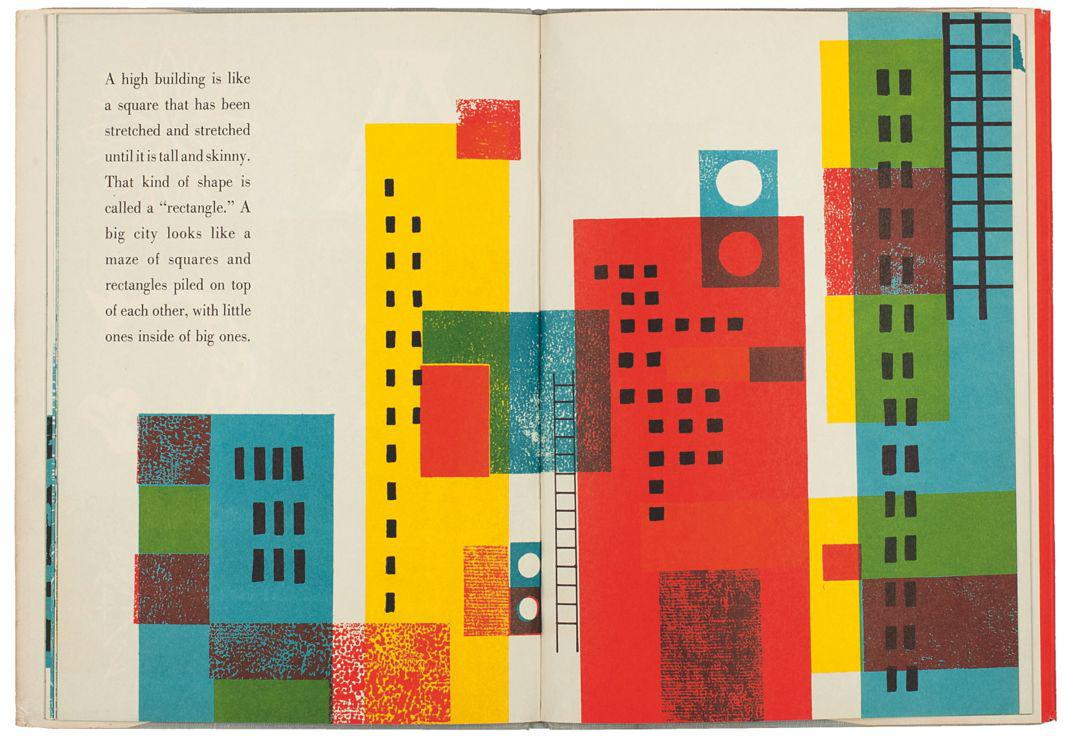

Helen Borten’s Do You See What I See? is an art primer to introduce children to the formal qualities of shapes, lines, and colors. It was a New York Times best-seller when it was published in 1959. “Although its use of limited colour and geometric motifs is redolent of the 1950s,” Salisbury writes, “its integration of word and image to explain the power of design was way ahead of its time.”

Courtesy of Laurence King

“In the course of my own work I encounter thousands and thousands of picture books, old and new, from all over the world,” Salisbury writes. “I have been fortunate enough to sit in judgement over them as a member of international awards juries at global book fairs. I have waded through the hundreds of publishers’ stands at those same fairs. On a daily basis I look at the sketchbooks, notebooks and picturebooks-in-progress of master’s students who are aspiring to a career in the field. Their passion for the subject is a continuing source of inspiration, and the thrill of seeing a beautiful picture book emerge from a sketchbook never leaves me.”

Courtesy of Laurence King