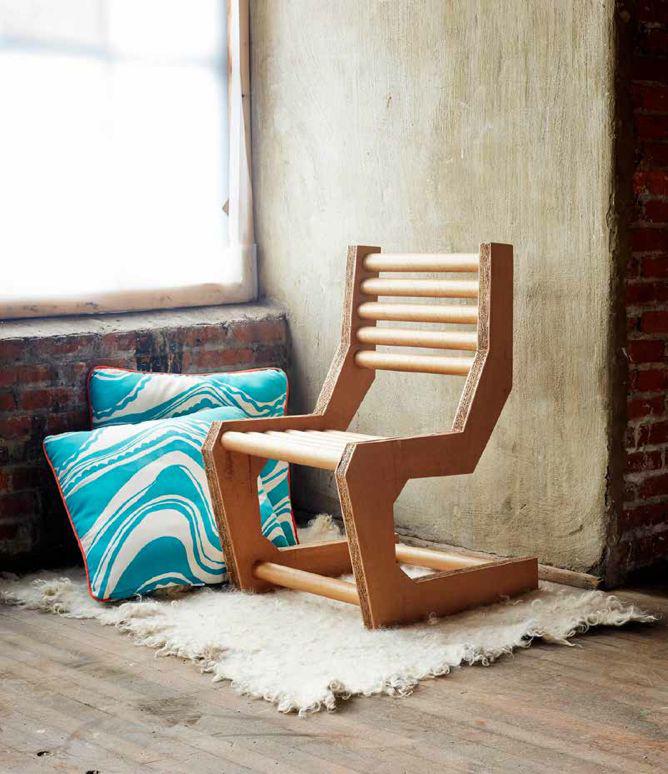

Will Holman’s new book, Guerilla Furniture Design: How to Build Lean, Modern Furniture With Salvaged Materials, is a manifesto and a how-to manual for building cool DIY furniture and household objects from paper, wood, plastic, and metal (like the lounge chair above, a new design that didn’t make it into the book but can be accessed along with other work by the designer on Instructables and OpenDesk).

In the book, Holman offers an outline of the history, sustainability principles, and philosophy behind his DIY ethos. In the following excerpt from the book, he talks about how his personal narrative of being an itinerant young designer in search of a job shaped his guerrilla design view.

Courtesy of Will Holman

I graduated with a degree in architecture from Virginia Tech in May 2007. In June, I packed a van, moved home, and spent a restless summer unsuccessfully searching for work in Baltimore. In August, I put a backpack in the back seat of my ’98 Corolla and drove West. I arrived in Cordes Junction, Arizona, one week later.

Designer and author Will Holman.

Photo by Kip Dawkins Photography. Courtesy of Storey Publishing.

For the next year I lived at Arcosanti, an experimental community an hour north of Phoenix. Founded in 1970 by Italian architect Paolo Soleri, Arcosanti is a prototype arcology, a dense urban system designed to produce its own food and energy. Eager to learn, I worked in the construction department, welding and pouring concrete, expanding the city. The wide-open country was gorgeous, the people warm and welcoming. I spent my Saturdays rooting around Arco’s boneyard, home to 40 years’ worth of construction debris, scrap metal, scaffolding, and old cars. Dragging fragments back to the workshop, I welded pieces together to create furniture for my co-op apartment.

In the summer of 2008 I headed back to Baltimore, straight into the nascent headwinds of the Great Recession. I spent the next year working at a custom cabinetry shop. At night, I sent out résumés and designed my own projects, hoping the economy would rebound. Architecture firms were devastated by the housing collapse, work was slow, and nobody was hiring. I put aside my architectural dreams for a time and concentrated on developing my woodworking skills, tutored by the master craftsmen at my job.

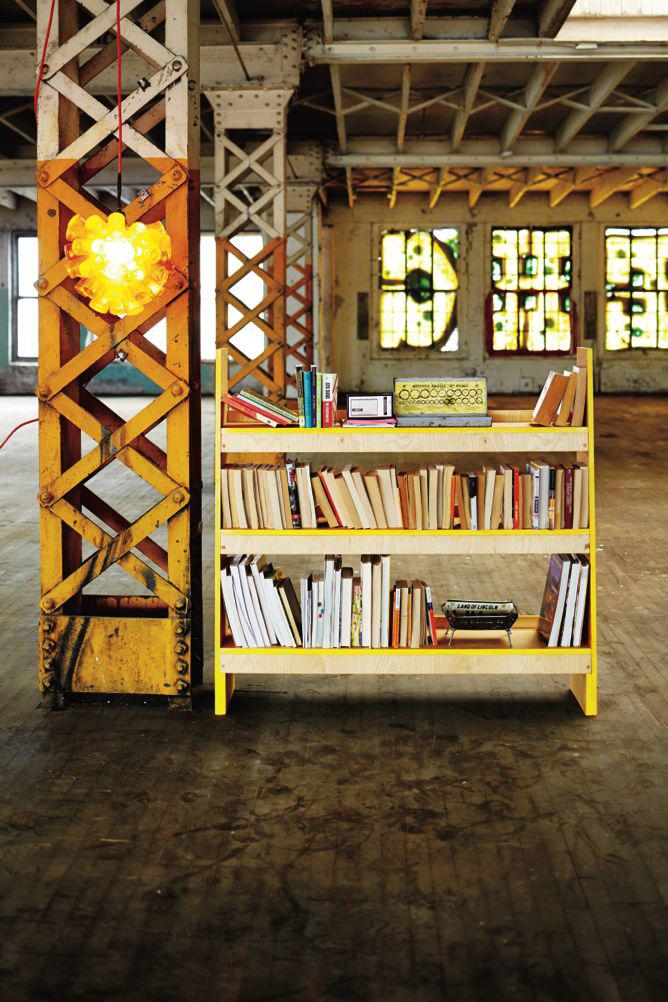

A pendant lamp made of empty prescription pill bottles.

Photo by Kip Dawkins Photography. Courtesy of Storey Publishing.

Photo by Kip Dawkins Photography. Courtesy of Storey Publishing.

In the spring of 2009 I applied to the Rural Studio. Founded in 1991 by Auburn University professors Samuel Mockbee and D.K. Ruth, the Rural Studio is an architectural design-build laboratory in Hale County, Alabama. I was accepted into their Outreach program, figuring I could wait out the recession for one more year.

The studio was (and still is) engaged in a long-term research project—the 20K House—meant to address the lack of decent low-income housing in the rural South. After eight months at the drafting board, my teammates and I built the ninth 20K House in about 50 days. Our client moved in at the end of June and parked himself on the porch, sitting in a rocking chair I made out of construction scraps.

Will Holman calls his carboard version of a 1920s cantilever chair “a guerilla take on the most iconic of modern forms.”

Photo by Kip Dawkins Photography. Courtesy of Storey Publishing.

School over, I looked for jobs across the South—in New Orleans and Birmingham—and back in Baltimore. Nothing came. I managed to rustle up some renovation work around the small town of Greensboro, Alabama, where I was living, spending weeks scraping and repainting the old tin roof on an antebellum home.

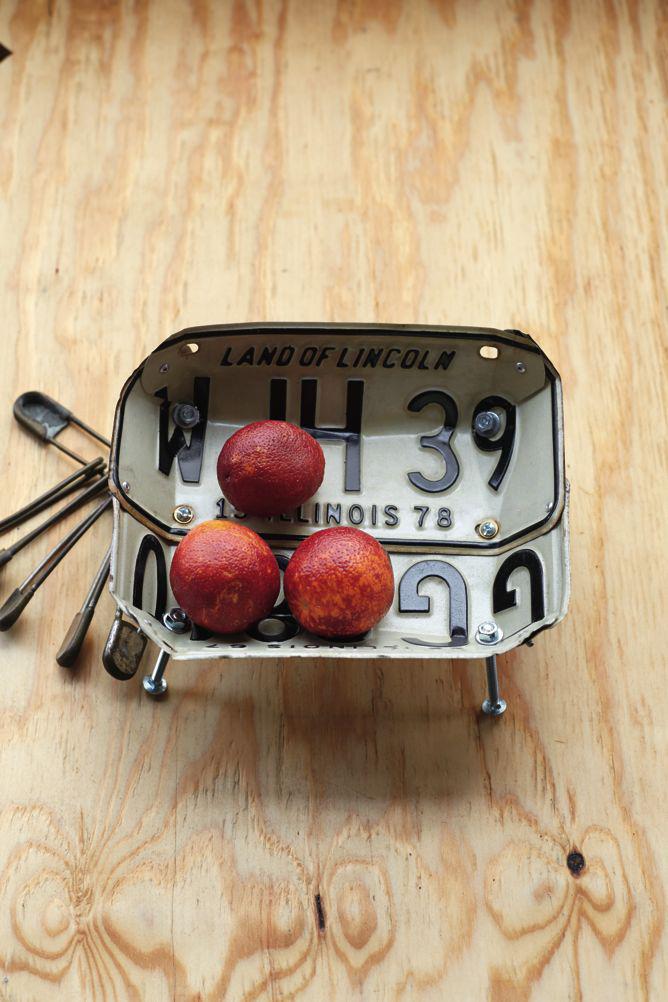

In late summer I got a job with YouthBuild, a local nonprofit that taught trade skills to young folks (coupled with GED classes) and paid them a small stipend for doing work around the community. That year we built a big vegetable garden, bordered by a fence made of old road signs from the county dump. On the weekends I tinkered with bending extra signs into chairs.

YouthBuild’s grant was cut in June 2011. I was out of work and in the wind, again. This time, I pointed the Corolla north, to Chicago, with a tiny U-Haul in tow. But salaried jobs were hard to come by, even in the big city, so I patched together a freelance career—building furniture, writing articles about woodworking, teaching design to teenagers, and working for an artist renovating a group of derelict buildings on the South Side.

The Scrap Table is 12 feet long, made with multiple pieces laminated with glue and threaded rods.

Photo by Ryan LeCluyse. Courtesy of Storey Publishing.

Photo by Kip Dawkins Photography. Courtesy of Storey Publishing.

Many of my friends, co-workers, and former classmates were in the same boat, hustling in a gig economy where steady work seemed increasingly difficult to find. I recently moved again, halfway back across the country, to my sixth apartment in as many years.

This time, work and life conspired to land me back in my hometown. Baltimore—like Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, or St. Louis—is a Rust Belt town, scarred by violence, corruption, factory closings, and population loss.

Battered as it may be, Baltimore is unbroken, populated with scrappy artists and makers who are experts at living on the margins. I’ve taken on a fellowship at a local nonprofit working to develop space for artists in the Station North district. We are leveraging cheap real estate and ubiquitous media into a new culture of making, reimagining our industrial heritage with modern tools.

My design sense was shaped by nomadism, recessionary economics, and the great abundance of America’s waste stream. Over the years, it would have been easy to furnish my varied apartments with thrift-store finds and big-box buys. Instead, I looked at each move as a fresh start, a new opportunity to solve a set of old problems: how to get me, and my stuff, off the floor. With little money, few tools, and improvised workshops, I shaped my environment out of paper, plastic, wood, and metal. Guerilla Furniture Design is meant to help you do the same.

Excerpted from the book Guerilla Furniture Design by Will Holman with the permission of Storey Publishing.