Pop-up parks, open streets initiatives, and other short-term community-based projects have become DIY tools in the arsenal of urban activists, land-use planners, and policymakers looking to make their cities better places to live. Tactical Urbanism: Short-Term Action for Long-Term Change by Mike Lydon and Anthony Garcia, out Tuesday, is a history of the Tactical Urbanism movement from two of its founders, as well as a toolkit for those looking for ways to improve their communities without get strangled in bureaucratic red tape.

The following adapted excerpt is about the guerrilla wayfinding effort Walk [Your City], a project to encourage walking initiated in Raleigh, North Carolina, in 2012 by concerned citizen Matt Tomasulo that is now being used by walkability advocates, community organizations, and city planners elsewhere.

If the 20th-century city was about inviting people to drive everywhere for everything, then the city of the 21st is about inviting them to walk. Although 41 percent of all trips made in the United States are 1 mile or less, fewer than 10 percent of all trips are made by walking or biking.

Economic, public health, and environmental gains are correlated to neighborhoods designed to support walking, but the supply of walkable neighborhoods in America is low. Yet one recent study shows that millennials favor neighborhoods where walking is convenient at a rate of 3 to 1.

Walkability is really just shorthand for everything that creates a neighborhood’s desirable character: mixed-use quality architecture, density, pedestrian-oriented street design, and proximity to parks and usable public space.

What happens when all these factors are present in a neighborhood but most people living there don’t walk much anyway? On a cold, rainy night in January 2012, a 29-year-old North Carolina State graduate student named Matt Tomasulo went looking for answers.

In 2007 Tomasulo had moved to Raleigh to pursue a dual master’s degree in landscape architecture and urban planning. He found a fast-growing, highly suburban, auto-dependent city of 425,000 residents. Tomasulo chose Cameron Village (Walkscore: 80) because of its proximity to campus and range of services within walking distance. Yet few people walked, even in his historic neighborhood built for exploring on foot. “They would drive two minutes just to get dinner,” Tomasulo says.

Courtesy of Matt Tomasulo

People told him they didn’t walk because it was “too far” to get from point A to point B. So he began mapping the distance between popular destinations, quickly discovering that a majority of respondents were at most a 15-minute walk from where they wanted to go.

He knew he couldn’t permanently change land use, urban design, or infrastructure overnight, but he believed he could tackle people’s misperception of distance by providing more information. What if the city could display signs with the names of popular local destinations, directional arrows indicating where to walk, and the time it would take the average person to get there? And what if people could scan a QR code on that sign to get directions instantly?

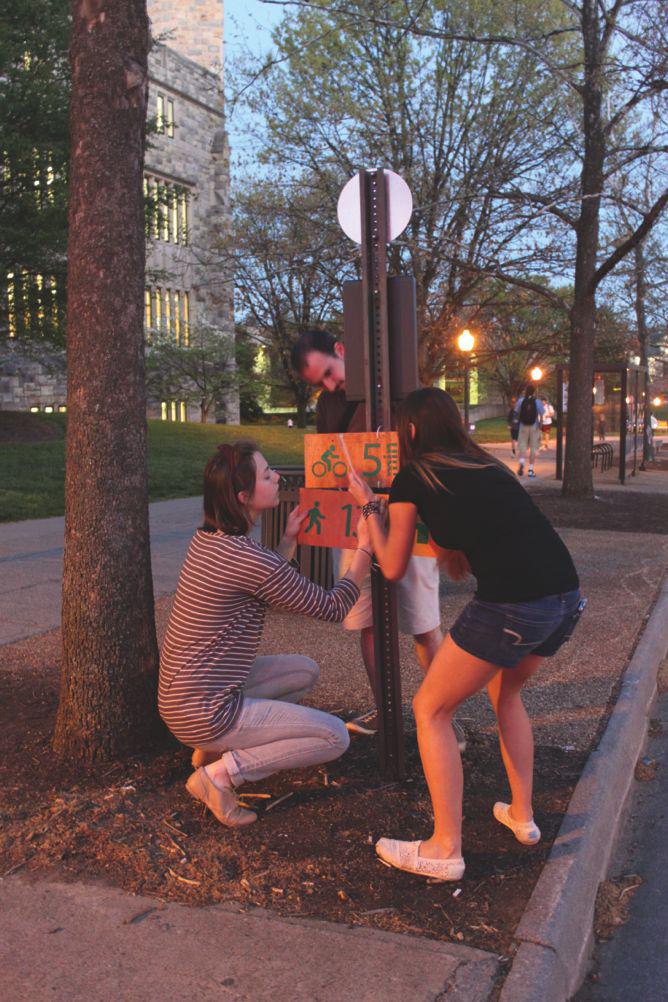

The city of Raleigh had a number of policies that encouraged walking. But Tomasulo didn’t have the money or the patience to work within city guidelines, so he devised a wayfinding project in line with government policy that he planned to implement without government permission. He designed lightweight, inexpensive “guerrilla wayfinding” signs made from corrugated, weather-resistant plastic sheets that could be attached to telephone or street lamp poles with zip ties. He hung 27 signs, dubbing the project “Walk Raleigh.”

“I very intentionally did not deface public property,” Tomasulo says, adding that equally illegal real estate signs found on lawns and telephone poles across the city often remain in place for months on end. “Walk Raleigh at least had a civic purpose and was consistent with the city’s stated goals,” he says.

Before posting the signs he had secured the domain name walkraleigh.org and created a Walk Raleigh communication platform via a Facebook page and a Twitter handle. Tomasulo knew the QR codes could help track the number of people interacting with the signs. Within days the Facebook page received hundreds of “likes,” and the story began to make its way around the urbanist blogosphere and attract media attention. But when one too many news outlets asked why the technically illegal signs were still up, the city responded by taking them down.

Raleigh citizens protested, so the city moved quickly to figure out how to reinstate the campaign, making the project a “pilot program” of the city’s comprehensive plan and asking whether Tomasulo would be willing to donate the signs back to the city for a three-month, city-sanctioned pilot project. The city officially recognized that the project was consistent with its goals to increase nonmotorized mobility, enhance bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure, and even expand wayfinding signs.

Courtesy of Michael Kulikowski

Tomasulo changed his master’s project to focus on scaling the Walk Raleigh project initiative. He envisioned a Web platform where anyone could log on, customize his or her own signs, and have them shipped within days—zip ties included.

To widen the appeal beyond his city, Tomasulo changed the name of the project from Walk Raleigh to Walk [Your City] and turned to Kickstarter to help raise the funds. The Kickstarter staff took a shine to his project and promoted it on the site’s front page, where it garnered more than $11,000 in funding from 549 supporters.

By July 2012 Tomasulo had built a small team and created a beta version of the Walk [Your City] template that provided sign templates for free download. It soon inspired guerrilla wayfinding projects in cities including New Orleans; Rochester, New York; Memphis, Tennessee; Dallas; and Miami. Tomasulo built out the Walk [Your City] website, which allows anyone to not only customize the digital sign template but also to purchase the desired number of signs and have them shipped to a specific location within days, along with instructions and best practices for hanging the signs.

The platform has attracted more than 10,000 sign template downloads and is being used in city and citizen-led projects around the world. “People in communities as small as 1,500 people to as large as New York City have used the signs,” Tomasulo says. “It’s low-cost and highly scalable. We’re proud of that.”

Back in Raleigh, the North Hills neighborhood has installed 93 signs, and in January 2013, the city of Raleigh voted to allow the sanctioned use of Walk Raleigh signs.

So where does the project go next? Will cities across North America begin to use temporary wayfinding signs while the dollars are scraped together for permanent signage? Will the Walk [Your City] effort bring in enough revenue to be sustained for others to use? Does it actually increase walkability in cities? We don’t have the answers to all those questions yet, but Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina is betting that Tomasulo is on to something. In early 2014 the health care giant provided Tomasulo with enough funding to hire his first full-time employee to help guide the implementation of the tool in three different pilot cities across the state. The company views it as a preventive measure against obesity. And CityLab reported in February that the Knight Foundation is planning to fund a large-scale expansion of the project.

“It is really exciting to see the attitude change,” Tomasulo says. “We just want to build a culture of walking.”

Adapted from Tactical Urbanism: Short-Term Action for Long-Term Change by Mike Lydon and Anthony Garcia, with permission from Island Press.