Massimo Bottura’s book, Never Trust a Skinny Italian Chef, is a heady trip into the thoughtful mind of the three-Michelin-starred culinary genius behind Osteria Francescana in Modena, Italy. Both a global citizen and a deeply Italian chef’s chef, Bottura counts Ferran Adrià and Alain Ducasse as mentors, has an American wife, and invents dishes inspired by cultural icons like Thelonius Monk and Picasso. The walls of his restaurant, one of the world’s best, are an ever-changing gallery of contemporary art that is more mission statement than decoration. Italy is his material, but art is his metaphor, the conceptual and critical lens through which he approaches and assesses his innovative reinventions of Italian culinary traditions.

Here at The Eye, Bottura shares an adapted excerpt from his book in which he discusses how he discovered the links between art and cooking and explains how a painting of a Ferrari inspired a radical redesign of the ultimate Italian classic: lasagne.

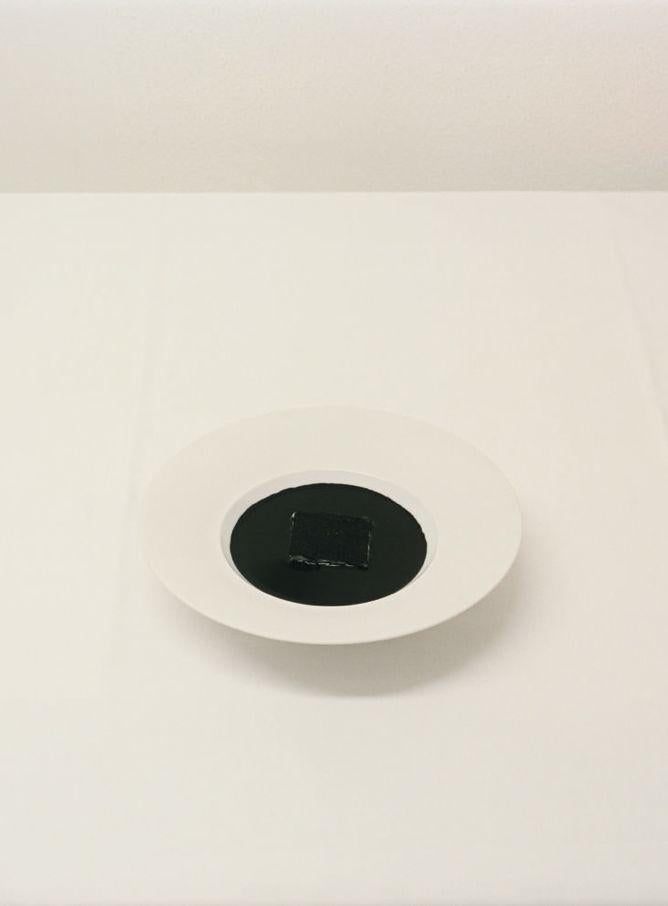

Photo by Carlo Benvenuto

Like so many things in my life, art was a chance encounter. It all began when I met my wife, Lara, who walked confidently through the strange world of contemporary art. Soon after we met, she introduced me to art, avant-garde theater, and performance art that I had never heard of or even imagined existed, and most of which I did not understand. Over time my suspicions waned. I began to see the parallels between the apparently disparate worlds of art and cooking.

Photo by Carlo Benvenuto

Lara and I forged relationships with art galleries and traveled to exhibitions, Biennales, and art fairs. We began to collect art. We were not afraid of placing odd and unexpected artworks in the restaurant. We changed the art frequently, moving paintings and sculptures around like ingredients on a plate. With each addition, our walls began to speak.

Photo by Carlo Benvenuto

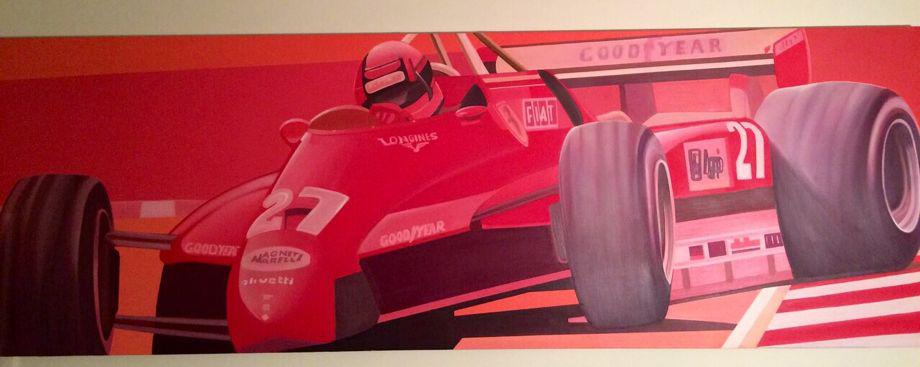

A painting of a Ferrari by Gian Marco Montesano placed next to Vanessa Beecroft’s photograph of a formation of Navy Seals addressed chaos and order. A sculpture of solid glasses by Carlo Benvenuto and a bronze garbage bag by Gavin Turk triggered reflections on the poetry of the everyday. Drawings made with a box of colored markers by Ceal Floyer addressed the conceptual nature of child’s play. An aerial photograph of Rome by Grazia Toderi reminded us of how important distance is to understanding culture. A series of needlepoint images from La Vie en Rose by Francesco Vezzoli invited music, beauty, and suffering into the picture frame. Olafur Eliiasson’s landscapes, like Matthew Barney’s Cremaster film stills, revealed real and imaginary worlds. And the pigeons … Maurizio Cattelan’s Tourists were installed in the restaurant, just as we had first seen them at the Italian Pavilion at the 1997 Venice Biennale, as a reminder of how all this madness had started.

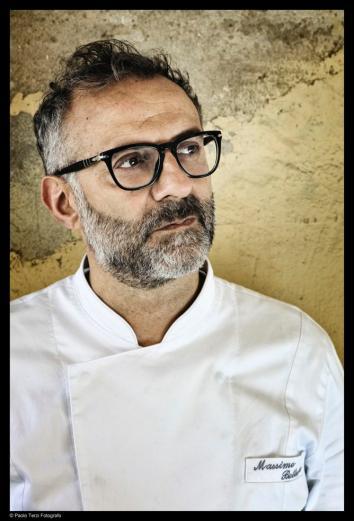

Courtesy of Paolo Terzi

In time the art found its way into the kitchen, and before we knew it, art became our landscape of ideas, firing our palates and our recipes with imagination. In addition to influences from the visual arts, music, and literature, it became a reference point for a kitchen that was determined to move forward, beyond tradition, beyond technique, beyond our horizons. We had never considered art a decoration, but a way of expanding beyond our physical confines, letting us see beyond the medieval city of Modena while remaining within it.

In October 2000 one of the most influential Italian restaurant guides published a scathing review of Osteria Francescana. It began: “The ambiance, if you don’t look at the ugly painting of the Ferrari, isn’t bad. … As for the rest, it wouldn’t take much for things to improve because in addition to technique, good flavor and originality at all costs, a plate also needs heart … ” I felt attacked on all fronts: my taste in art, my recipes, and, most importantly, my soul. What were we doing wrong? I would have defended Gian Marco Montesano’s Ferrari painting La Dame et Son Chevalier (The Lady and Her Knight) with my life. It embodied the spirit of the legendary Ferrari driver Gilles Villeneuve. The artist had captured an instant of distorted fate, with the front tires nearly melting off the canvas. The painting made visible that ephemeral moment between victory and destiny.

Courtesy of Lara Gilmore

The artwork on the walls of Osteria Francescana has never been a question of decoration. Paintings work like visual metaphors, or bridges that lead guests toward the ideas in the kitchen. Maybe the restaurant critic did not understand this premise, or that Emilia is riddled with contradictions. For one, slow food and fast cars. The tractor engines that harnessed glory from the earth were made in the same factories as the motor car engines that would one day leave the fields and take to the race tracks. The Ferrari painting in the dining room testified that agriculture and machinery are intertwined in Modena. There are the long silences of the aging process of Parmigiano Reggiano, prosciutto, and balsamic vinegar as well as the noisy battery of the metal, carbon, and steel that produce roaring engines that challenge gravity. Enzo Ferrari was a man with a passion for speed and a vision of the future. He took everything to the extreme. Could we take lasagne to the extreme, making it both technically correct and perfectly designed, fast and light like a Ferrari?

Italians grow up eating lasagne. There is no season nor occasion that does not merit lasagne. I was notorious for stealing the edges of the toasted top layer, which I considered the best part, before the pan left the kitchen. Who hasn’t been tempted to break off the crisp corners flavored with juices from the ragù? A fast and light lasagne sounded like a contradiction, but I was confident that if the flavors were abundant enough they could be reduced to minimal gestures. On lightness, the poet Paul Valéry observed: “One should be light like a bird, not like a feather.” Light is flight.

With this idea in mind, we designed a lasagne like the air jets of the 312 T4 Ferrari, one of the fastest models, but one that was never praised for its beauty. On each pasta triangle, boiled and then baked for crispness, there are alternating layers of ragù and bechamel, one after the other. An entire dish made from the best part of the lasagne.

Photo by Carlo Benvenuto

Gilles Villeneuve raced in 67 Grands Prix and never won a single world championship. Some say he was the last great driver; in our minds he won every race. We held our breath as he risked his life at every curve. After the devastating review we felt like Villeneuve and his car spinning out of the picture frame. With La Dame et Son Chevalier, we chose to take the next curve even faster, to risk everything.

Adapted with permission from Never Trust a Skinny Italian Chef (Phaidon) by Massimo Bottura, $59.95, copyright Phaidon Press Inc.