For three decades, Mark A. Landis conned the art world by deftly copying works by great artists then donating his forgeries to dozens of museums under his own name and a roster of assumed names and identities that ranged from philanthropist to a priest.

But in 2008, his nonmercenary but questionable antics were discovered by a museum registrar named Matthew Leininger, who appointed himself lead detective on an obsessive quest to expose and stop Landis. (Landis has never faced prosecution for his actions, which, while clearly deceptive, have not been found to be illegal.)

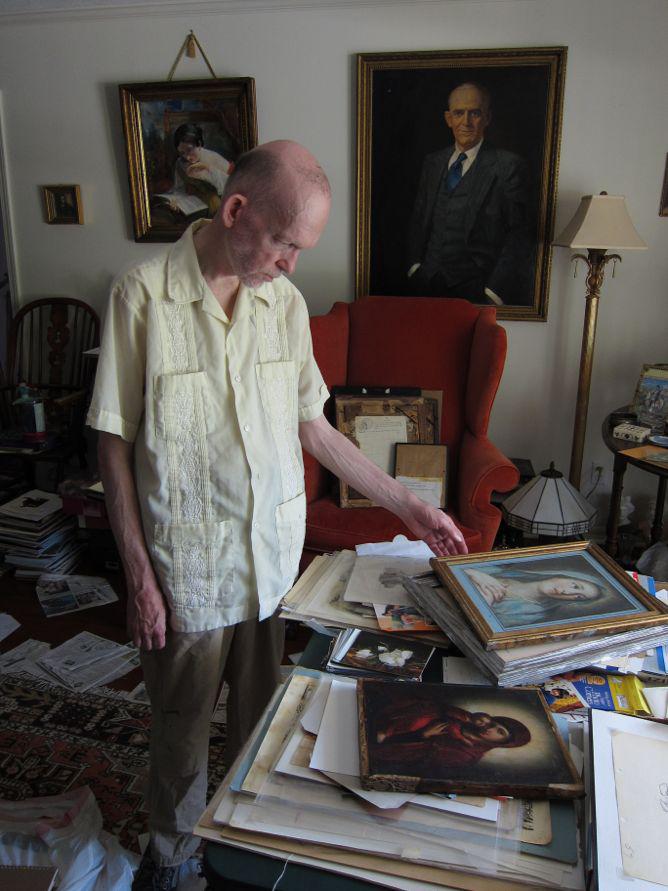

Mark Landis at home, showing off some recent forgeries.

Photo by Sam Cullman. Courtesy of Oscilloscope Laboratories.

An article in the New York Times about Landis inspired Art and Craft, a new documentary directed by Sam Cullman and Jennifer Grausman (with co-direction by Mark Becker) that opens in New York City on Friday. But even for those familiar with the story, which has since been covered around the world, the documentary presents a compelling look at Landis himself and the surprising process he used to reproduce 15th-century religious icons, Picassos, and Walt Disney characters using supplies from local craft stores in Laurel, Mississippi, where he lives.

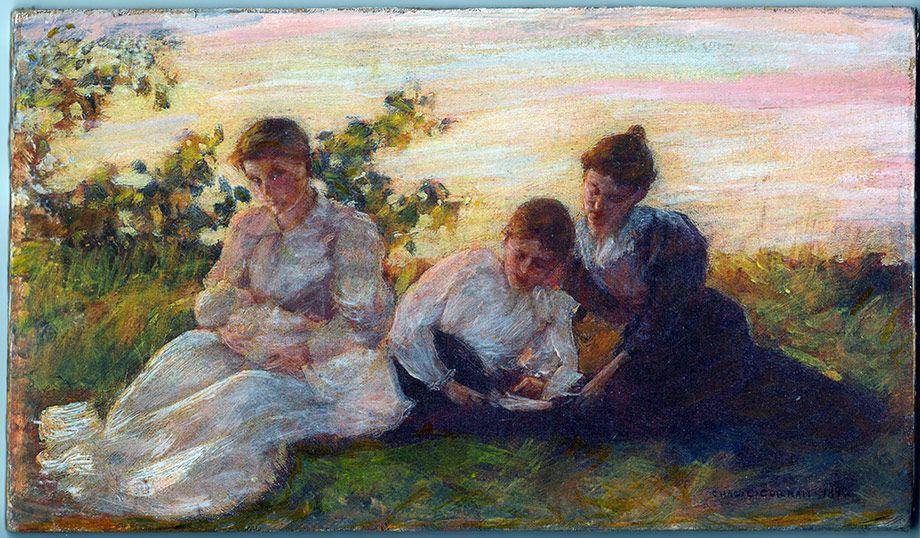

Copying pictures from catalogs was a habit Landis picked up as a child while traveling in Europe with his parents, who would leave him alone in hotel rooms in the evenings. “It’s reassuring,” he says in the film. Over the years, he perfected a technique in which he would place a sheet of paper directly over a catalog painting and flip it back and forth between the image and the paper, able to hold the image in his mind just long enough to copy it. In the ensuring years, he has developed an arsenal of tricks: photocopying images from catalogs blown up to the size of the originals to use as templates, using coffee to stain the backsides of framed works to age them convincingly—all while watching old TV and films in his bedroom.

Courtesy of Oscilloscope

Landis learned about Picasso’s Blue Period from a movie, not art school. He didn’t grow up fantasizing about becoming an artist, he says, but a philanthropist, the kind of characters in old movies set in and around the art world seemed like they were getting the kindest attention and having all the fun.

Far from a central-casting version of a slick con artist, Landis is nevertheless a compelling leading man in this gently told portrait of his life. Born in 1955 and diagnosed with schizophrenia at age 17, he lives alone in his deceased mother’s apartment. He has a measured, Truman Capote–esque speaking voice. He is often medicated in a way that alters his affect but never dulls his wit. Once found out, he seemed genuinely if naively concerned that people are angry at him for what he did.

When explaining his motivation, he says that he is simply making use of his gifts. “I have no delusions about being any sort of … great artist,” he says, when asked why someone of his skill and determination doesn’t devote his energy to his own work. “I decided to be a philanthropist,” he says.

Landis remains a mysterious figure, even after this intimate portrait tells his story. But listening to him talk does offer the occasional epiphany as to why a man of such talent and skill has only one original work of art to his credit: a portrait made after a photograph of his young mother. After spending several years in a mental institution starting at 17, Landis studied photography, but he never earned a degree. Once he had learned basic photography skills, he said, “I couldn’t think of a thing I wanted to photograph.”

Courtesy of Oscilloscope