In her excellent new book Factory Man: How One Furniture Maker Battled Offshoring, Stayed Local—and Helped Save an American Town, award-winning journalist Beth Macy tells the story of John Bassett III, a third-generation factory owner and descendant of Virginia’s Bassett Furniture family, which once ran the world’s largest wood furniture manufacturing company before cheap Chinese imports put an end to all that. A rare success story, Bassett took on the Chinese by filing the world’s largest anti-dumping petition—and winning in 2005. Bassett is now the chairman of Vaughan-Bassett Furniture Co., which employs some 700 people and has sales of more than $90 million. Here at the Eye, Macy shares an adapted excerpt from the book that explains how the Chinese began to decimate the U.S. furniture-making industry beginning in the 1980s—and how Americans helped them do it.

It took a Chinese native, living in Taiwan and educated at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, to figure out how to capitalize on the new importing landscape in the late 1970s. As a young man, Larry Moh had fled communist China under Mao with his family, later marrying into a wealthy Taiwanese family that included two brothers-in-law—Harvard MBA graduate Ronald Zung and his brother, Laurence Zung, a Ph.D. in chemistry.

There was now a hotel boom in Hong Kong, part of an industrialization wave that was bringing American businessmen to East Asia by the hordes. China’s growth was still modest, an exception in Asia at the time, with just 17 percent of its population living in cities (compared with half today). The so-called Asian Tigers of Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, the Philippines, and Hong Kong were already roaring, providing China with strong examples of economic possibility from every side.

But under the iron fist of Chairman Mao, China remained poor, agrarian, and isolated, partly by choice and partly as the result of an American embargo involving a ban on all transactions with China through 1972. China was at the beginning of what Marx called “primitive accumulation,” in which the bulk of a working population transitions from working the countryside to working under the smokestacks in cities and towns. Its evolution from farm to factory was a half-century behind the American South’s, although China would undergo the transition in a much shorter time span under Deng Xiaoping’s market economy quest.

Larry Moh understood with certainty that Asia was ripe for industrialization, and with his new furniture company, Hong Kong Teakworks, he and his brothers-in-law borrowed $80,000 and positioned themselves to take full advantage. Brother-in-law Ronald was sent to North Carolina State University to learn the ins and outs of furniture manufacturing, while brother-in-law Laurence was dispatched to find a furniture-grade lumber the company could use in Asia—other than the prized but expensive native teak—so they wouldn’t have to import hardwood from the United States.

Photo by David Hungate

Rubberwood was plentiful in nearby Malaysia, and it was grown in groves, where it was tapped for latex, like American maples for syrup. Rubberwood went into the making of tires, condoms, and rubber gloves, and when the sap became too thick to extract—typically when the trees reached their mid-20s—they were usually felled. With its high sulfur content, rubberwood attracted bugs, and the two countries where it was most prevalently grown—Malaysia and Indonesia—were humid, causing mold and insect problems. The trees decayed so quickly that felled rubberwood was known to turn to Jell-O in as few as 10 days. Once a rubberwood tree no longer produced latex, it was deemed unharvestable and burned.

Until Laurence Zung came along and figured out how to turn garbage into gold. “You had to be one step ahead of the bug,” he recalled. When he applied the correct concentration of a chemical called pentachloride to the raw rubberwood, he realized, he could repel the insects without staining the wood. Hong Kong Teakworks could count on using rubberwood in furniture-making, with results akin to hardwoods grown in the American South.

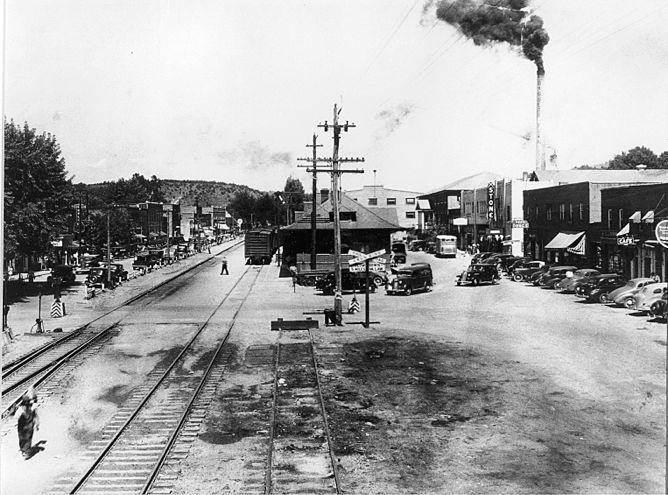

Courtesy of the Bassett Historical Center

Not only would the lumber be free, but regulations in Hong Kong were scant and labor costs next to nothing, with production workers making 76 cents an hour against an American factory worker’s $6.36 in 1975.

So Moh and his brothers-in-law built a factory on two floors of a Hong Kong high-rise and set out to expand the Asian furniture offerings far from the usual wicker and rattan. With urban space at a premium, the high-rise didn’t allow for the typical loading dock setup. They installed ramps literally inside the building, allowing trucks to deliver materials and haul the finished goods away from the higher-level floors.

They started out specializing in hotel furniture, designed wider to fit the heftier shapes of American business travelers. “You had all this trade building up with big Americans going over there who didn’t like the smaller, Asian-styled furniture,” analyst Jerry Epperson recalls.

Photo by David Hungate

Making American-sized hotel furniture was a natural beginning for Moh and his brothers-in-law, and hotel owners ate it up because they could charge more for the larger rooms that housed it. But like the toymakers and textile producers before him, it dawned on Moh: Why couldn’t he build furniture designed for sale in American stores, just like the carmakers in Japan were doing?

Within a few years, Moh’s company, now called Universal Furniture, had factories in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan. Unlike the Italians and Koreans who had long exported furniture for their immigrant cousins in the United States, Moh was the first to export furniture from Asia for consumption in middle America. “From a visual point of view, it was identical to what we were buying here,” Epperson said. It was basically Bassett Furniture—less, of course, 20 to 30 percent the cost.

American consumers ate it up.

So it went that Moh became the first Asian to clobber the Southern furniture-makers exactly where they’d punched the guys in Grand Rapids, Michigan, a century before—with free hardwood and dirt-cheap labor. And the most surprising thing of all? Moh was so proper and polite, practically Southern in the way he went about conducting his business, that the Americans taught him exactly how to do it.

Adapted excerpt from Factory Man: How One Furniture Maker Battled Offshoring, Stayed Local—and Helped Save an American Town, by Beth Macy, reprinted with permission from Little, Brown and Company.