In the recently published Bicycle Design: An Illustrated History, authors Tony Hadland and Hans-Erhard Lessing offer a comprehensive and authoritative survey of nearly 200 years of cycling technology and design. Here at the Eye, they highlight 10 pivotal moments in the design history of the bicycle.

When one of us tried to put a quintessential bicycle history on Wikipedia in 2010, an anonymous Wikipedian immediately overwrote the text, commenting that “No single time or person can be identified with the invention of the bicycle.” Today, Wikipedia has a specific entry on bicycle history, indicating the growing interest in this long neglected area of the history of technology. But it has a limited scope and also contains debunked myths, such as the claim that the Scotsman Kirkpatrick Macmillan built the first crank-driven bicycle, or that Leonardo da Vinci invented the bicycle.

After attending 20 International Cycling History Conferences alongside academics, curators, and collectors, we knew the statement “No single time or person can be identified with the invention of the bicycle” to be misleading. The conferences have established a clear sequence of innovations and well-identified inventors that led to the bicycle of today—and, by the same route, to the automobile.

This inspired us to write a book built on the research presented at the conferences, which we hope will put an end to inaccurate histories, errors copied from one book to another and invented anecdotes, such as the claim that the bicycle was “invented for the narrow paths of German forests.” At a time when we are commemorating the outbreak of World War I, it’s worth noting that many of the debunked bicycle creation myths arose from late 19th-century nationalism. Every advanced country wanted to claim the bicycle as its own invention.

Below we offer our Top 10 19th-century bicycle innovations, most of which are still in use. These innovations are landmarks of bicycle evolution, as well as the beginnings of the bicycle components that are easily recognized by any user of the bicycle today. We also pay tribute to their inventors, who we feel deserve the same fame as automobile pioneers.

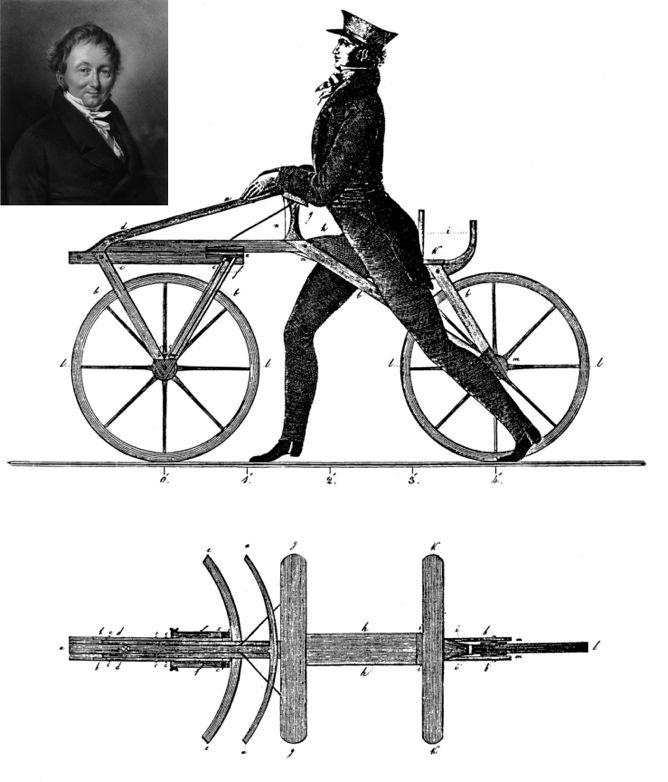

Portrait courtesy of H.-E. Lessing; drawings by Drais, circa 1817 via MIT Press.

1817 - THE DRAISINE

Karl Drais’ counterintuitive discovery that a vehicle with two aligned wheels could easily be balanced by tiny actions was the technical breakthrough from which all bicycle development stems. His 1817 “Laufmaschine” (running machine) or “Draisine” was meant to replace horses starved after the Tambora eruption brought the year without a summer in 1816. It was scooted forward with one’s feet on the ground and was raced at speeds of 14 miles per hour. Its success in the western world was curtailed by legal restrictions and the return of horses after the good harvest of 1817.

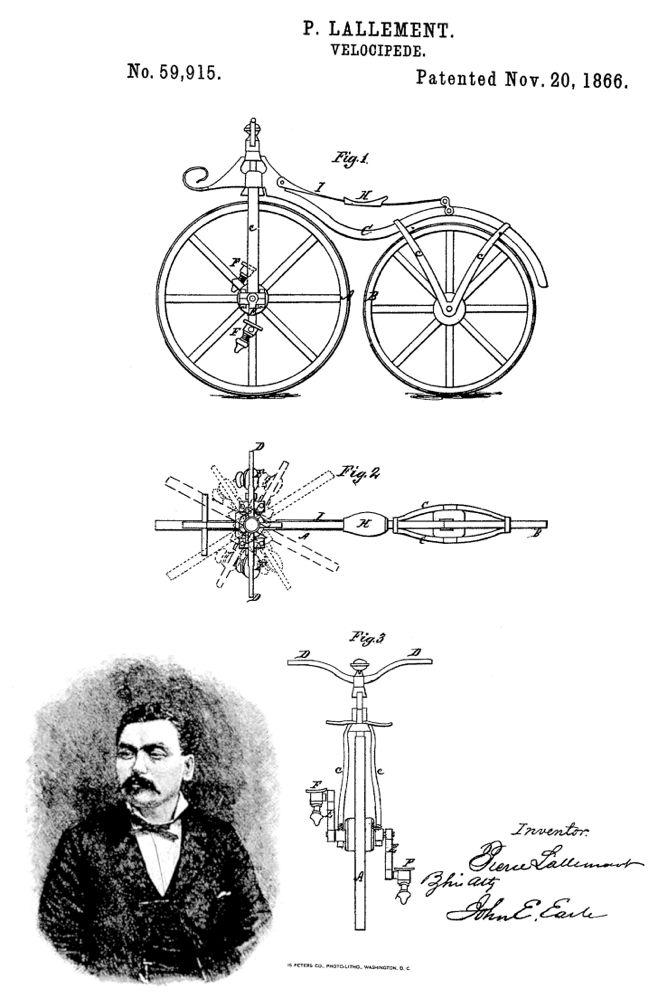

Courtesy of MIT Press

1866 - THE CRANKED TWO-WHEELED VELOCIPEDE

For decades, the growth of railroads stole the show from early two-wheelers. (That, and the fact that people were frightened of balancing on them.) But around 1865, somebody in France dared to take both feet off the ground and onto cranks for pedaling the front wheel, proving that it was possible to balance on a bike and crank at the same time, and thus spawning a new boom. These added cranks on the front wheel formed a wholly new cycling concept, and soon the machines were made of metal rather than timber. Who came up with the cranked front wheel idea is still fiercely debated but we know that French cartwright Pierre Lallement emigrated to the United States and took out a patent in 1866. At home he couldn’t become a national hero because his last name sounded like l’Allemand, the French word for the German, then the archenemy. Meanwhile in France, the Olivier brothers used Pierre Michaux as a front man for their business, producing cranked velocipedes in significant numbers, soon spreading to the U.S. and U.K.

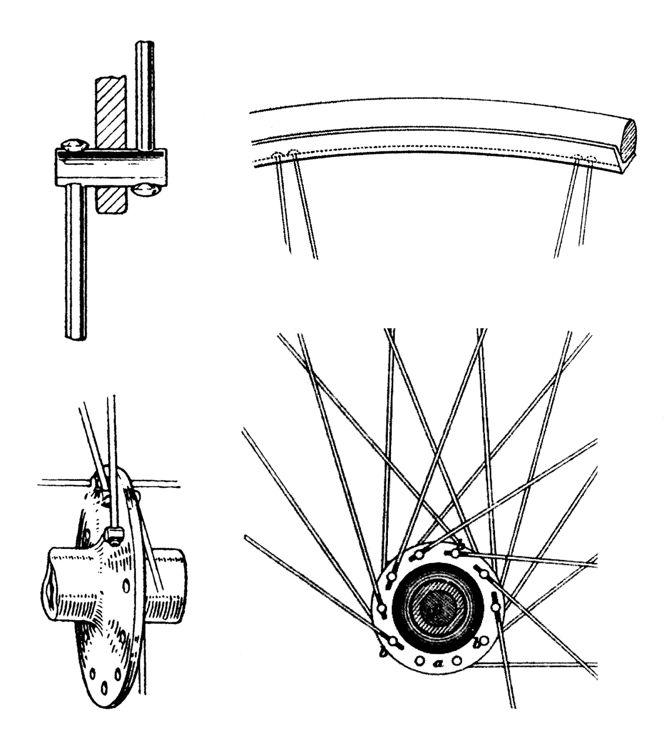

Courtesy of Keizo Kobayashi via MIT Press

1869 - THE TENSION-SPOKED WHEEL

Races began to be organized regularly by velocipede clubs in France starting in 1869. When wooden spokes were replaced by steel tension wires—as patented by an Alsatian in Paris named Eugène Meyer—it was a breakthrough moment. Huge front wheels could now be built for higher speed, limited only by the inseam of the rider. Meyer, an unsung hero, had been forgotten until recently because his name was misspelled and couldn’t be traced at the patent office. His velocipedes were the era’s most beautiful and were ridden by top racers. When the French racers brought these high wheelers to England in 1870, they were seen and immediately improved upon by James Starley.

Courtesy of MIT Press

1874 - TANGENT SPOKING

James Starley is regarded as the father of the British cycle industry. His first patent on spokes provided a means of tensioning them in unison by slightly twisting the hub relative to the rim. The lightweight structure of the spoke wheel would crumble immediately, were it not for the tensioning of the spokes to make it stable. As Meyer’s machines were unknown, Starley’s “Ariel” design, derived from that patent, was long regarded as the earliest high-wheeler or “bicycle,” as these machines were then called in the United Kingdom. Still better was the tangential spoke arrangement of Starley’s next patent, preventing the spokes from being broken by the rotational thrust of the pedal crank. Tangent spoking became the world standard.

Drawing by R. John Way; courtesy of MIT Press

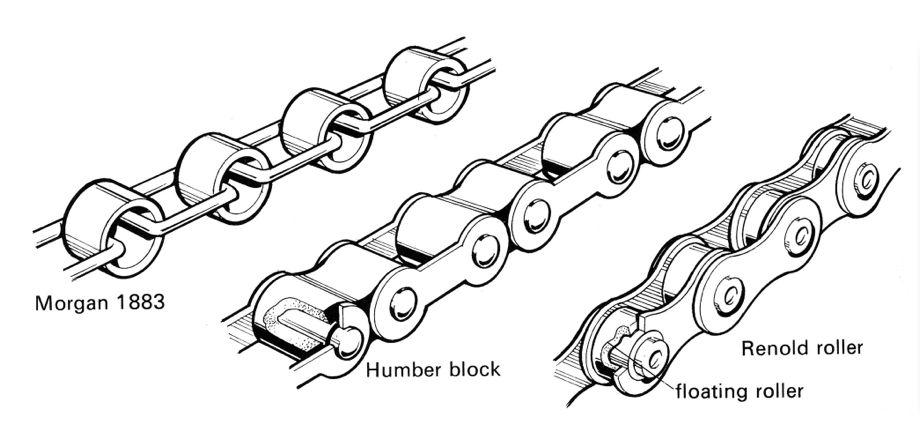

1880 - BUSH-ROLLER CHAIN

The idea of using a chain to transmit power to the drive wheel of a bicycle, instead of pedaling cranks directly fixed to the front wheel, was being discussed in the British technical press by the mid-1860s and several French inventors patented chain-driven bicycles. In 1880, Swiss-born Hans Renold invented the bush-roller chain at Manchester, in which pairs of inner and outer links were riveted together. The inner chain links rotated on the rivet pins and had bushings on which ran loose rollers, providing a large, rotating, low-friction bearing surface for the sprocket teeth. Bush-roller chain became a world standard. The rider enjoyed minimal resistance to pedaling and no longer had to fear the breaking of his chain.

Courtesy of MIT Press

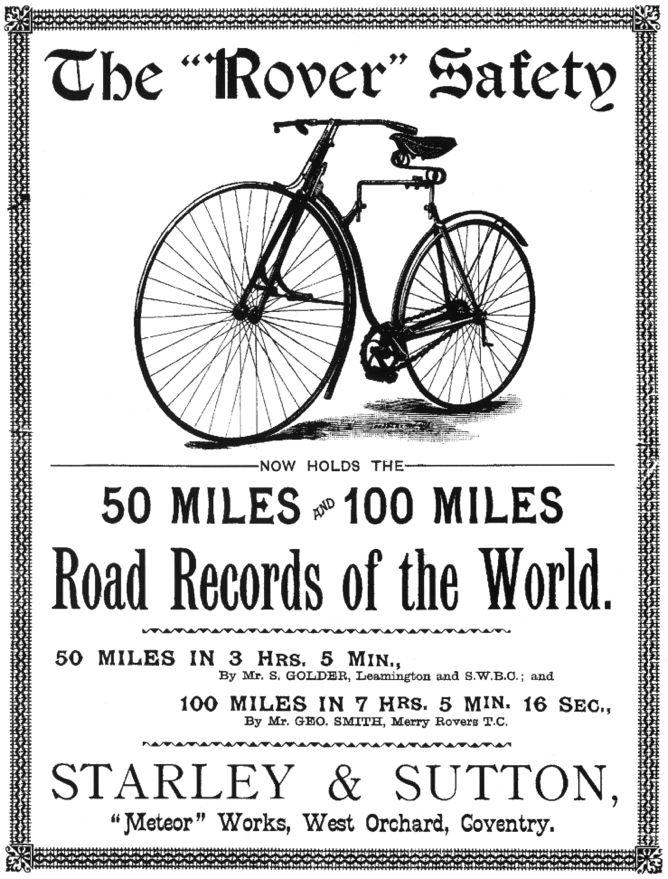

1885 - THE ROVER SAFETY BICYCLE

Although the high-wheeler was efficient and fast, it was difficult to ride safely. Bicycle makers and inventors began to develop lower, safer bicycles, with geared-up rear-wheel drive, eliminating the need to sit atop a huge front wheel. John Kemp Starley, a nephew of James Starley, created the first rear-driving bicycle to attain widespread popular favor. The 1885 Rover Safety had most of the hallmarks of what was to become the standard bicycle. It featured direct steering of the front wheel, wheels of similar size, a diamond-shaped frame and chain drive to the rear wheel.

Courtesy of Dunlop Tyres UK via MIT Press

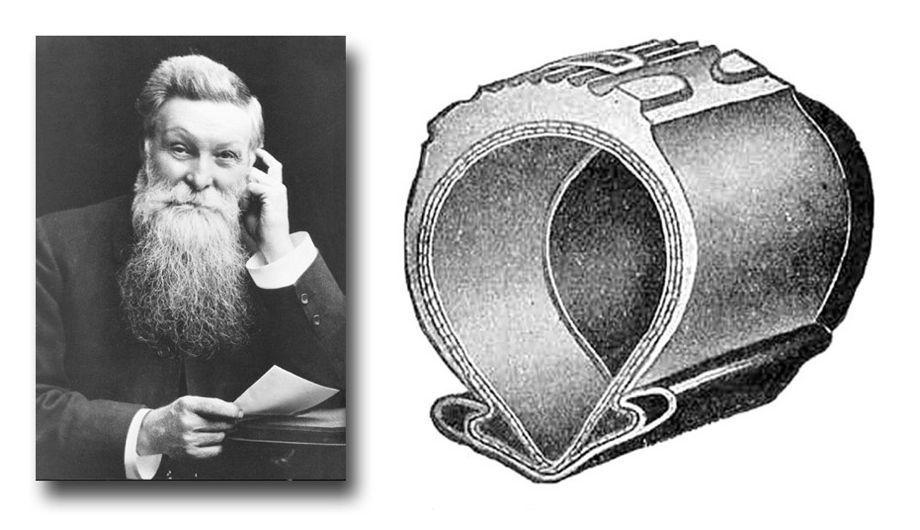

1886 - PNEUMATIC TIRES

A Scotsman named William Thomson patented the pneumatic tire in 1845, but it was not commercially successful and was soon forgotten. Another Scot, John Boyd Dunlop, reinvented the idea in 1886 and its efficiency for an easier and less bumpy ride was demonstrated in winning races from 1889 on. Dubliner Harvey du Cros took the lead in organizing the Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co. and bought up other patents, including some that improved on Dunlop’s design making it detachable for better repair of punctures. In the early 1890s, bicycle makers rapidly adopted pneumatic tires and they were soon standard equipment.

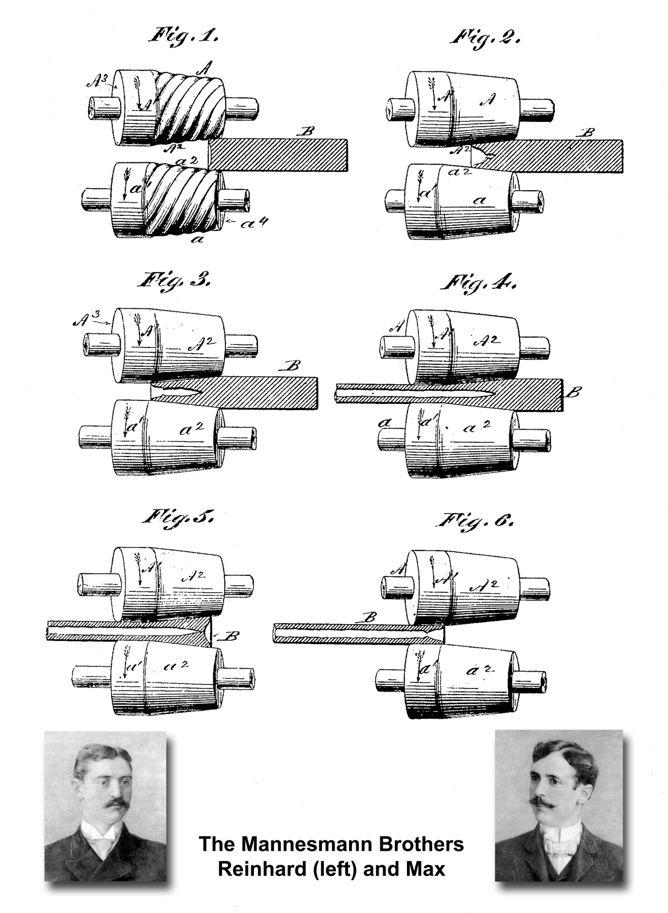

Courtesy of Salzgitter AG-Konzernarchiv/Mannesmann-Archiv, Mülheim an der Ruhr via MIT Press

1887 - TUBE ROLLING

With the market for bicycles growing, manufacturing became based on the principle of the division of labor, as in automobile production. A tiny but important bicycle part, the cotter pin, used to fasten the left side crank, did not withstand for long the enormous forces during pedaling. Max and Reinhard Mannesmann, heirs of a small German rolling mill, tried to harden their cotter pins by rolling them. Unexpectedly, they observed that this produced a central void in the steel. They combined this discovery with an existing process and could now convert a solid steel bar into a seamless tube within seconds. Their invention came at the right time to satisfy the lightweight “tube hunger” of the bicycle industry. A former employee circumvented their patent and grabbed the U.S. market. For many decades, the vast majority of quality bicycles have been built of lightweight seamless steel tubing, as pioneered by the Mannesmanns.

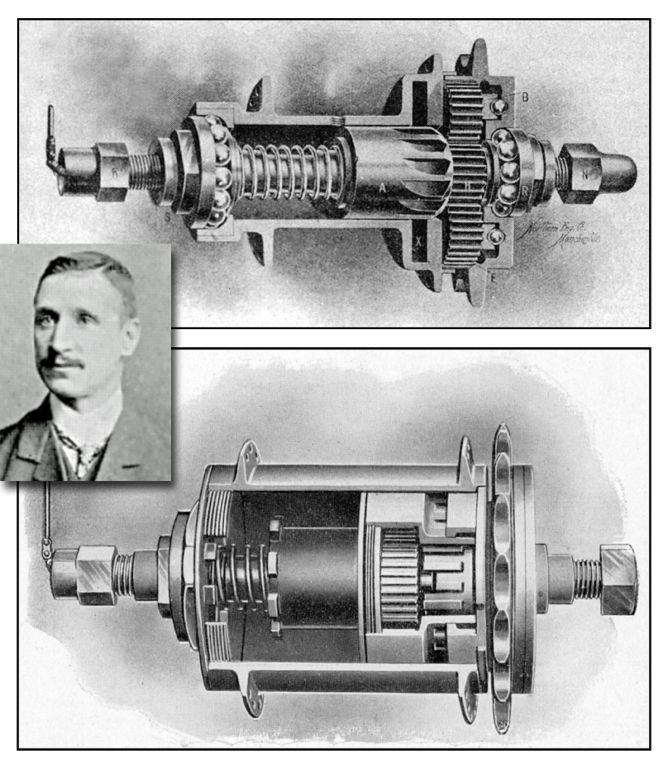

Portrait courtesy of National Cycle Library; bottom image courtesy of Sturmey-Archer Heritage via MIT Press

1898 - HUB GEARS

The idea of variable gears, to help cyclists match their power output to gradients and wind conditions, dates back to the 1860s. A breakthrough came in 1898, with the first commercially successful compact hub gear. Its inventor was William Reilly of Salford, England. Known simply as “The Hub,” it was a tiny 2-speed based on planetary gears. Because bicycle chain-drives gear up for speed rather than down for power, the torque in a bicycle hub is much lower than it is at the cranks. Hub gears can therefore be made smaller and lighter than gears on the crankshaft. Reilly went on to design the first Sturmey-Archer 3-speed hub, launched in 1902. It was easy to use, efficient and low maintenance. Sturmey-Archer became for many decades the market leader for bicycle gears in the U.K. and elsewhere, before makes like Bendix, Fichtel & Sachs (now SRAM), and Shimano appeared.

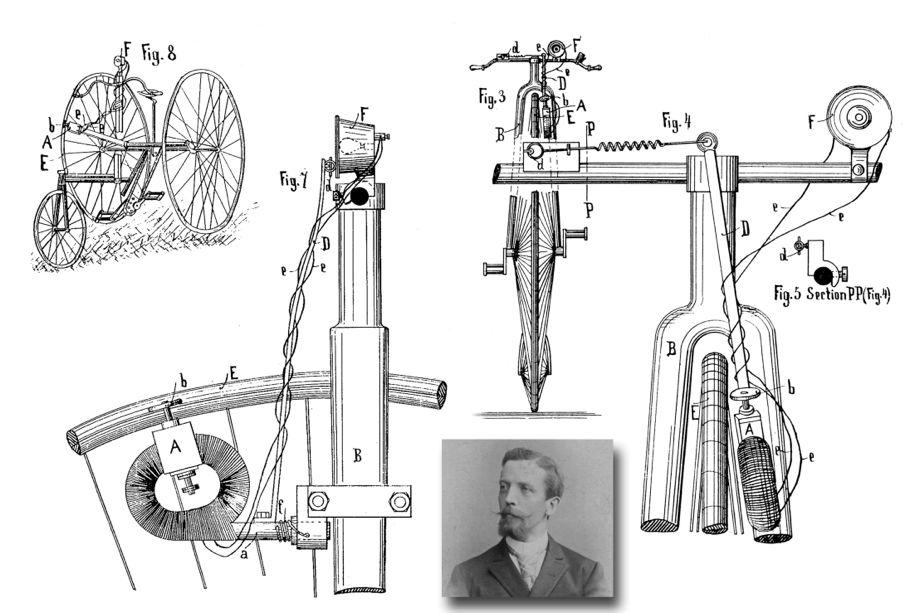

Richard Weber and his 1886 dynamo patent.

Portrait courtesy of Gerd Böttcher via MIT Press

1911 - THE DYNAMO

Bicycle lighting started in 1817 with sheet-metal candle lanterns, continued with oil lamps, and culminated in bright acetylene-gas lamps in the 1890s. Electric lighting started in the U.S. about the same time, but the bumps of the road destroyed batteries and the filaments of the costly bulbs. In 1886, Richard Weber, a mechanic in a Leipzig shop that sold camera holders for bicycles, patented his idea of a small generator driven by the bicycle wheel to illuminate an electric bulb. The idea became commercially viable when the jolt-resistant tungsten filament appeared in 1911. Since then bicycle dynamos have been produced in vast quantities.